UC Santa Barbara researchers exposed lab raised California red-legged frogs to the chytrid fungus, treated them and then released them.

Researchers with the University of California, Santa Barbara inoculated threatened California red-legged frogs (Rana draytonii) against chytrid fungus by exposing them to the fungus in the laboratory. The reason was to determine if the immune systems of these frogs could be activated , giving them better protections once were released into the wild.

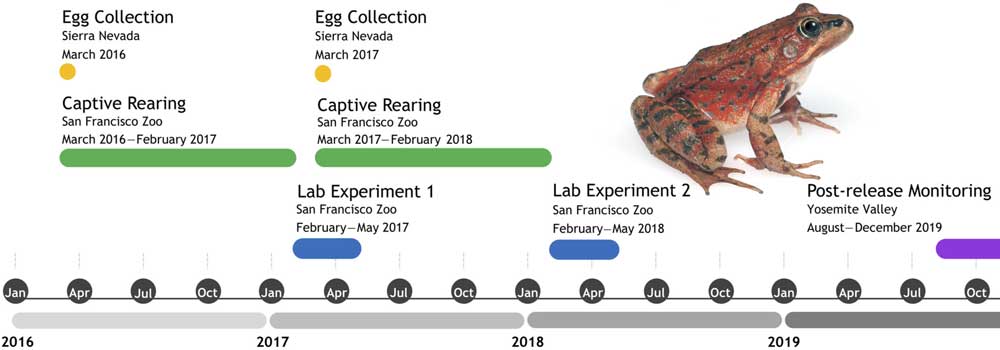

Study timeline. California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii) photo credit: Robert Hansen

The researchers collected red-legged frog eggs about 100 miles northwest of Yosemite Valley in an area where the frog is thriving. They then raised the eggs in captivity at the San Francisco Zoo. After the frogs reached the juvenile frog or froglet stage, the researchers gave 20 of the amphibians a cocktail bath of live and active strain of the fungus, Andrea Adams, researcher in ecology at the university wrote in a press release detailing the study. Three weeks after exposure, the frogs were then given an antifungal drug to stop the infection. An additional 40 frogs that were not exposed to the live fungus were given an antifungal bath. The researchers then exposed the original 20 frogs to the fungus a second time and then exposed 20 previously unexposed frogs to the fungus. This was to determine how the twice exposed frogs would compare to those exposed to the fungus just one time.

Chytrid Fungus More Prevalent In Baja CA Red-Legged Frogs Than In Southern CA Frogs

California Red-Legged Frogs Breeding In Two SoCal Locations

The Return of Red-Legged Frogs to Southern California

“After release to the wild, we observed no differences in field-contracted Bd infection among exposure groups. Treating post-metamorphic R. draytonii ex situ may not confer additional post-release benefit to this species in terms of chytridiomycosis burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, “To treat or not to treat? Experimental pathogen exposure, treatment, and release of a threatened amphibian” “Our results, however, do not necessarily mirror Bd susceptibility throughout the amphibian life cycle, with other source populations that may have different Bd infection histories, or responses to different Bd strains. These results provide a clearer understanding of post-release disease responses of a threatened, Bd-susceptible species with prior pathogen exposure. Following ex situ experiments with in situ applications can provide a more comprehensive understanding of threat outcomes for declining species in reintroduction programs and strengthen critical links between ex situ and in situ conservation partners.”

The researchers found that 35 percent of the frogs that were infected with the fungus were able to clear the infection without vaccination or using an antifungal drug. The research say that the frogs have some innate immunity to the fungus, successfully warding off the fungus. The frogs infected twice with the fungus had a 31 percent overall lower rate of infection than those infected just once. This suggests the treatment also stimulates adaptive immunity. Adaptive immunity simply means the immune systems of these frogs learned to recognize and fight the fungus from the first exposure. The researchers also noted that no frogs died as a result of the fungal exposure.

The frogs were then treated with an antifungal drug before they were released into the wild. The frogs were outfitted with tiny transmitters to track their infections and survival during the first three months of their release. They also found no difference in disease burden between both classes of frogs. They think that immunizing the California red-legged frog for chtyrid in Yosemite Valley might not be needed to ensure their survival after reintroduction. The frogs released after the experiment are thriving in their new locations.

The complete research paper, “To treat or not to treat? Experimental pathogen exposure, treatment, and release of a threatened amphibian” can be read on the Ecosphere ESA Open Access Journal.