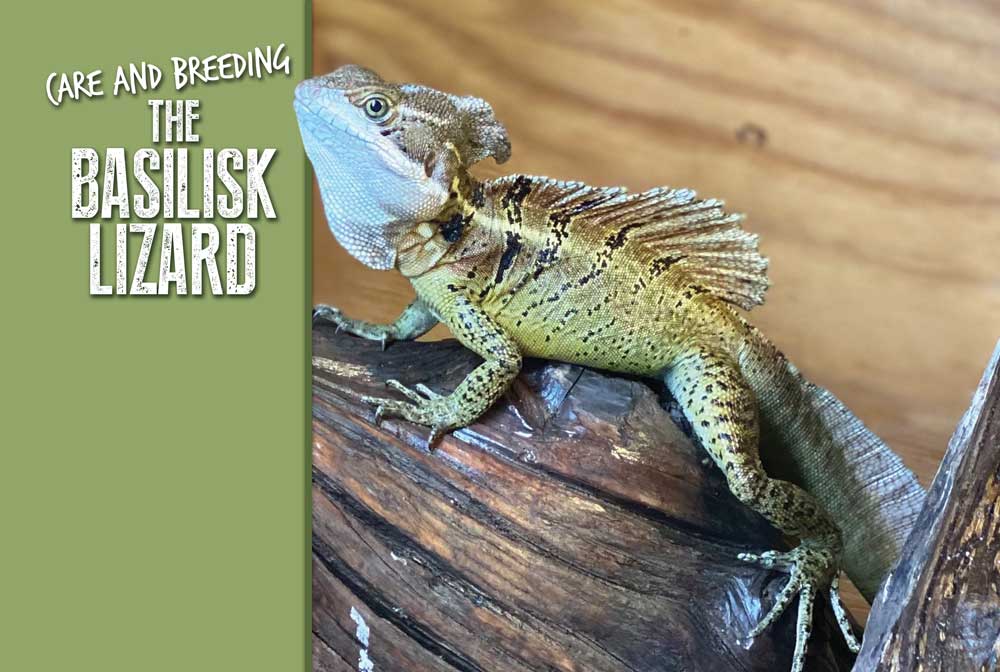

Basiliscus basiliscus is a beautiful species for advanced keepers.

My affinity for basilisk lizards began when I was in the 7th grade, as a wide eyed 12-year-old budding herpetologist. It would be some 25 years before I moved my focus to this family of lizards. In 2009 I built up a group of plumed basilisks (Basiliscus plumifrons), with the goal of not only breeding them but also tackling some of the challenges that perplex keepers regarding the development of captive animals in comparison to their wild counterparts. I have had amazing success with this species, breeding many hundreds over the years. Additionally, I have learned a great deal about their natural history in captivity.

Multiple basking sites of varying temperatures and lighting are ideal for this species. Photo by Eric Haycraft

That success led to a desire to expand into other species of basilisks. However, practically gone from the hobby were Basiliscus basiliscus, the common basilisk. Common basilisk is a bit of a misnomer, both in terms of geographic range and availability within the hobby. It is, in fact, not common. For years I patiently searched and eventually in 2014 found a European breeder and acquired two babies. Those both grew into adult females. I was disappointed but still happy to be a little bit closer than if I had zero of this species. It would be some years later in 2019 that a surprise import would land in America. I was fortunate to build a group of 14 sub-adults. My next project within this family was officially under way.

Captive History of the Basilisk Lizard

Over the years I had read every book, scientific journal, and magazine article I could get my hands on about basilisks. In November of 2004, Bert Langerwerf contributed an article about the various species of Basiliscus he was working with to this very publication you are reading now. Bert contributed many great articles to REPTILES magazine, and I read each one of those.

Langerwerf penned an article about breeding basilisks that I have read countless times and looked at the old photographs, hoping for a chance to work with these just as Bert did.

As my group of common basilisks matured, I soon found the same success with this species that I have found with the plumed basilisks. With the emergence of social media as a platform for hobbyists and keepers to share their experiences, I could document my experiences in real time. It did not take long for other keepers to take note of my projects and last year I was contacted by Russ Gurley. Russ, who has written many books on reptiles, had helped Bert write his book, “Lizard Man: The Life and Adventures of Bert Langerwerf.”

Basilisks require very large enclosures. Photo by Eric Haycraft

Russ had decided there was enough demand to reissue the book and he wanted to upgrade a new book with more, new and better photographs. Russ asked if I would mind offering photos of my animals for the book. Additionally, Russ was creating a second volume that would be a collection of nearly every article Bert ever wrote, including all of the articles from REPTILES magazine. Russ explained that Bert’s basilisk article would be reissued as well, with the addition of my photos. What an incredible honor. Now here I am penning an article on my successes with basilisks in the very publication that inspired so much of what I am doing within herpetoculture and to follow along the road that Langerwerf paved.

The Common Basilisk

The common basilisk (Basiliscus basiliscus) ranges from Nicaragua, south through Costa Rica, Panama and into Colombia, where it is represented by a subspecies. While the common basilisk is quite common within its range, the striped basilisk, Basiliscus vittatus, has a quite larger and more extensive range, from Panama north through Mexico and across southern Florida. Additionally, striped basilisks inhabit far more diversified habitats. These two species will often be lumped into a shared common name of brown basilisk.

Plumed Basilisk Lizard Care Tips

Basilisk Lizard Information And Care

Over the years the prevalence of striped basilisks, due to their invasive status and availability in Florida, choked out the demand for any common basilisk imports. Add to that the issuing of stricter export laws in countries such as Costa Rica, and the common basilisk essentially became absent from the hobby. Ultimately, this is probably for the best as adults do not respond well to being collected, shipped, housed in cramped quarters and then likely resold in pet stores. Of the hundreds imported, a tiny fraction survive the first six months. Captive-bred and born specimens prove much easier to acclimate successfully.

Housing Common Basilisks

Common basilisks are medium-sized, extremely active lizards. Mature animals should be offered sizable enclosures that allow them to run, jump, climb and swim. This species is best suited for larger custom-built enclosures. I keep trios and foursomes (one male to multiple females) in 8 feet long, 7 feet high and 4 feet wide enclosures half the year and larger outdoor enclosures during the summer. In nature they live along riverbanks and streams and have clear access to the full sun.

Basilisk lizards require very large enclosures with large water features. This enclosure features a 40 gallon pond built in. Photo by Eric Haycraft

A combination of UVB and light for heat is a must. Large enclosures are great opportunities to create multiple basking locations with multiple lighting strategies. I have found great success using T5HO tubes as well as mercury vapor bulbs. Additionally, I’ll add in a few locations with different temperatures using halogen bulbs and a metal halide bulb. All of these are at varying heights and varying intensity and set on timers to kick on and off strategically through the 12-hour cycle of day light.

I am fortunate to have climate-controlled rooms for most of my collection so I can manipulate the humidity to a range of 60-75% during the day and upwards of 85-90% at night during the rainy season and a bit lower through winter. Ambient temperatures run 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15.6 degrees Celsius) at night to 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30.0 degrees Celsius) peak day with basking spots allowing the animals to warm up as much as they choose.

I have 40-gallon ponds in each enclosure. I stock these with small, live bearing fish and crayfish. The lizards can hunt at their leisure. Additionally, I feed rotations of grasshoppers, mantids, crickets, superworms, roaches and night crawlers. Variety is very important when feeding these lizards.

Breeding Basilisks

Established basilisks with their basic needs met can be quite prolific. Breeding will peak in the spring and females will then produce clutches every few months of eight to 12 eggs. Female basilisks need a secure place to deposit the eggs. I have found raised planters work very well. I keep as many plants as I can to offer cover while the females excavate tunnels up to 14 inches long.

Babies hatching out. Once the eggs are laid, they are carefully transfered into an incubator. Photo by Eric Haycraft

The eggs are deposited at the bottom of the tunnel and the substrate is filled in and tamped down by the lizard. It is best to remove the eggs as soon as they have been laid. I transfer them to small dishes and incubate at temperatures of 79 to 84 degrees Fahrenheit (26.1 to 28.9 degrees Celsius). Extremely high humidity is best registering 95 to 100 percent. Eggs incubated in this fashion will hatch in roughly 65 days.

Basilisk Lizard Hatchling Traits

Hatchlings measure about 2.5 inches. They should be kept in tanks in groups. A 10-gallon enclosure is sufficient for 12 hatchlings for several months. Clean the enclosure regularly. They need access to the UVB and heat and will consume the same items as their adult counterparts, just much smaller. They are ravenous eaters and they grow quickly.

A colorful foursome of young basilisks thermoregulating. Photo by Eric Haycraft

In nature the hatchlings will stick together in groups, often multiple unrelated clutches banding together to form even larger groups. This safety in number strategy allows for the baby lizards to confuse would be predators (or well-intentioned keepers) by exploding in every direction with fast running lizards. Once the danger passes, they reconvene in the area. This is most readily apparent at night when the baby lizards will sleep stacked sometimes four deep across a branch. Unfortunately, most captive arrangements do not accommodate babies in large groups. This contributes to the high mortality rate of captive basilisks.

The Dorsal Sail of the Basilisk Lizard

The real challenge with basilisks in captivity is not necessarily keeping them alive or even breeding them. Captive raised basilisks, specifically males, tend to never develop dorsal sails and colors as their wild counterparts. Decades of speculation has blamed lighting and lack of sun, diet and even the need for a line of sight with other males to stimulate territorial behaviors. This issue plagues both the plumed basilisk and the common basilisk.

Dorsal sail of an adult basilisk lizard. Photo by Eric Haycraft

Over the years I have experimented with my own collection to try and tease out which of these factors may or may not be the key. The issue with experiments such as these is they take several years at a time. What I can say at this point is that while lighting is certainly a huge factor in the coloration of the lizards, it is not responsible for underdeveloped dorsal sails.

Keeping the lizards in line of site actually does not affect this outcome and may actually hinder development as males will fail to develop characteristics if stressed by constant line of site. While I have several generations of tests to confirm my hypothesis, my best data shows that the very best development comes from keeping the babies in sizable groups right up to the point secondary sex characteristics would begin to develop. Then isolating males from other basilisks all together for a period of 12-24 months. This becomes quite difficult for the average keeper to accommodate.

The less interaction the lizards have with people the better they develop. Lastly, any major moves or shipping should be done as early as possible. The process that starts the maturation process can be interrupted and once it has been interrupted it does not recover. This is why most basilisks grow into adulthood with very small dorsal sails. This lack of development does not affect the overall health of the animal and their offspring can go on to produce more normal characteristics still, given correct circumstances.

Basilisks are amazing lizards that thrive in captivity given the correct environment. They are active and intelligent and make fantastic display animals that demand attention. For the advanced keeper who seeks the challenges, they present one of the largest left in keeping lizards when it comes to the captive development issues. For years the same set hypothesis have been recycled with very little actual data to back anything up. As more captive-bred common basilisks work their way into the hobby, I have no doubt that this dilemma will be solved.

Eric Haycraft has been keeping reptiles and amphibians for over 40 years. The last 12 years have been producing basilisks and related lizards. Eric can be contacted on Instagram @casqueheaded.