The Minor’s chameleon breeds readily in captivity. You just need to find some.

The Minor’s chameleon (Furcifer minor), also known as the lesser chameleon, is one of the smaller, most beautifully colored and rarest of all chameleons. Once imported regularly, this gem disappeared from captive collections in the U.S. after Madagascar limited its exportation of chameleons to a few species. Luckily, several European breeders were successful in breeding the Minor’s, though, and eventually some captive-bred specimens of diverse lineage were imported into the U.S. several years ago, making the beautiful Minor’s chameleon once again available to a few hobbyists.

Frank J. Payne

Due to their size, Minor’s chameleons do not need overly large enclosures.

Furcifer minor is classified as an endangered species and will likely never be imported from the wild again. And while the species is still incredibly rare in captive collections, I have had relatively good success in breeding them and hope to be able to offer them to other hobbyists late in 2018 and into 2019. With this article, I hope to help potential keepers get ahead of the game in learning how to properly care for this amazing chameleon prior to its becoming more widespread in the U.S. With a responsible mentality and the correct lizard supplies, this species can thrive.

Frank J. Payne

Unlike most other chameleon species, the female Minor’s chameleon is the sex that displays the most vibrant coloration.

The Minor’s Chameleon Description

The obvious appeal of Minor’s chameleons is their intense and spectacular coloration. Unlike most other species of chameleon, it is the females that possess the most beautiful coloring. A female at rest is usually a pleasant shade of emerald green with bright red on the head and red and blue dots on the sides, accompanied by some yellow banding. When a female is gravid or unreceptive to an amorous male, she flashes her most spectacular colors.

Frank J. Payne

Male Minor’s chameleons possess two pronounced, side-by-side nose horns, while females have nubs.

Males typically exhibit a beige or gold coloration with some darker banding. When one is displaying to a female or another male he can become incredibly vivid and will also show black, orange and yellow coloration. The male of this species is also easily distinguished from the female by the two fairly large horns that project from the front of his head; females have only very small nubs on the face.

Minor’s chameleons are small, with females typically measuring around 6 inches in total length and males up to 9 inches. About half of the length is tail. The species’ small stature makes it an excellent candidate for hobbyists who are limited in space and cannot provide the larger enclosures that the more commonly kept panther or veiled chameleons require.

Even though it’s known as a delicate species, in my experience Minor’s chameleons are rather hardy and prolific as long as their needs are met. Of course, starting with healthy, captive-bred chameleon is an important first step to success. If you have had several years of success keeping and breeding the more commonly kept chameleon species for several years, then the Minor’s would make an exciting and rewarding next project for you. And because Minor’s are still incredibly rare in captivity, I think anyone who wants to pursue working with them should have captive breeding as a goal. Successful captive care includes the proper reptile products mentioned here along with prioritizing pristine husbandry, plus reptile health and wellness.

Handling Minor’s Chameleon’s (Try not to)

Minor’s chameleons, like most chameleons, are not good pets for regular handling sessions. They are generally non-aggressive and rarely attempt to bite, but they are often afraid of being handled and this should be limited as much as possible. Taking a chameleon out every few weeks for a detailed inspection or a photo shoot is not a problem if it’s limited to a few minutes. Allow the chameleon to walk on your hand; do not actually grasp the animal. In general, Minor’s chameleons are a beautiful “look but don’t touch” species to keep.

Frank J. Payne

Minor’s chameleon’s are afraid of being handled and this should be limited as much as possible.

The Minor’s Chameleon Enclosure

Chameleons should be kept singly, except when placed together for breeding purposes. I have successfully kept Minor’s chameleons in glass reptile terrariums such as those made by the large reptile product manufacturers such as Zoo Med, Exo Terra and Zilla, as well as in all-screen enclosures, such as Zoo Med’s Reptibreeze, that are typically recommended for chameleons. My current preferred method is to maintain Minor’s in enclosures that have solid sides and back and a screen front and top. You can create one of these yourself by cutting and affixing plastic panels (coroplast) to the back and sides of a readily available screen enclosure, or you can purchase one pre-made for use with chameleons from Dragon Strand (dragonstrand.com). Furcifer minor can thrive in all the enclosures mentioned, but your keeping strategies will vary somewhat depending on which type you choose.

Frank J. Payne

Enclosures for Minor’s chameleons should provide plenty of lizard habitat products, such as branches, for climbing opportunities.

Unfortunately, many people still dogmatically adhere to the false notion that chameleons can never be kept in glass terrariums. I disagree, as keeping chameleons in glass terrariums, as long as the enclosures have some front ventilation, is a great option for smaller species. Glass terrariums are great at holding heat and humidity, which means less frequent misting sessions and smaller wattage heat lights can be used. You can monitor humidity in your glass terrarium with reptile hygrometers. Glass terrariums can also be beautifully planted with a natural soil and live tropical plants. There are some considerations to keep in mind when using glass terrariums, though. First, fully planted glass terrariums are heavy! This is something to consider if you plan on moving in the near future. Second, chameleons need to drink droplets of water off leaves and other cage furniture, so misting is a necessity. If you use an automatic misting system, which I recommend, you have to be very careful to not overwater the enclosure. Too much water being added can quickly accumulate and create a stagnant mixture of water and soil at the bottom. You can also use a manual reptile mister such as the Exo Terra Reptile Mister.

Screen enclosures, on the other hand, are very light and easy to move but do not hold heat or humidity very well. Longer misting sessions and higher wattage basking bulbs are required when housing chameleons in them. Screen enclosures come with a solid bottom but they are not designed to hold water, so a method must be devised to collect the excess water that will be running out of the cage after misting sessions. The best way to do this in my experience is to use a custom-made PVC drainage tray. These are basically pans that have a slightly larger footprint than the bottom of the enclosure, with some struts on top of which the enclosure will sit (as if it’s on stilts). Water will run out of the cage and into the pan, where it can be removed via a bulkhead or a wet/dry shop-vac. These pans can be purchased from D.W. Geckos & Terraria (dwgeckos.com) and Dragon Strand.

Frank J. Payne

As mentioned, F. minor is still very rare in captivity, so finding some may be the biggest challenge.

I am not a fan of using all-screen enclosures for chameleons that are kept indoors because, in my opinion, too much heat, water and humidity escapes from them to create an ideal environment. This can be easily addressed, though by covering the back and sides of the enclosure with PVC or coroplast sheeting that is cut to size. The front and the top of the enclosure should be left as is. This keeps a lot of the heat, light and water in the cage where it belongs while still allowing for good air flow and a lightweight enclosure. Plus, such enclosures can also be easily moved outdoors, weather permitting.

The interior of the enclosure must be designed with the chameleon’s arboreal nature in mind. I like to use a large, live plant that takes up about half of the volume of the enclosure. My favorites are Scheffelera arboricola and Ficus benjamina. Both species are easily found, hardy, and they provide good climbing opportunities and cover for the chameleon. Many branches of various diameters should also be placed horizontally, diagonally and vertically within all the levels of the enclosure. This makes complete use of the enclosure volume as well as allowing the chameleon to thermoregulate itself by moving throughout different temperature zones from the top to bottom of the enclosure.

Being one of the smaller species of true chameleons, Minor’s do not require an overly large enclosure. I keep most of my adults in terrariums measuring 18 by 18 by 24 inches. I have occasionally had an animal that was more prone to roaming which was stressed in an enclosure of this size but did better in something a bit bigger. You can go as big as you want, but I would not keep an adult in anything smaller than 18 by 18 by 24 inches.

Minor’s Chameleon / Reptile Heating and Lighting Requirements

Minor’s are sun-loving lizards that enjoy bright light and a warm basking spot. All of my chameleon enclosures are outfitted with a dual-fixture fluorescent light strip, like the Zoo Med Reptisun 10.0 UVB Fluorescent Lamp. One of the bulbs is a 6500K spectrum bulb that will provide nice, bright, white light that is excellent for live plant growth. The other bulb is a UV-producing fluorescent light. I use and recommend Reptisun 10.0 and Arcadia 6.0 bulbs. It would be difficult to over-light an indoor enclosure, so you could add more light with LED strips (also 6500K) if necessary.

While temperatures should vary seasonally, I try to provide a basking spot of 90 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit and ambient daytime temperatures in the 70s.

A localized hot spot should be provided using a separate basking bulb. I like to use halogen floodlights as they provide strong, warm, and localized light. The specific wattage will vary depending on the size of the enclosure, the distance of the lamp from the branches, room temperature and whether the enclosure is made of glass or screen. Halogen bulbs are available in a wide variety in pet stores and online reptile shops. While temperatures should vary seasonally (more on this in the breeding section), I try to provide a basking spot of 90 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit and ambient daytime temperatures in the 70s. A reptile thermometer and thermostat (like the Zilla Habitat Controller) can be used to monitor these. A nighttime temperature drop should be provided and can be created by simply turning off all the lights at night. A reptile timer can be used to set these times so you don’t have to rely on doing this manually. No extra heat should be provided at night if the enclosure is kept in a room at normal room temperatures.

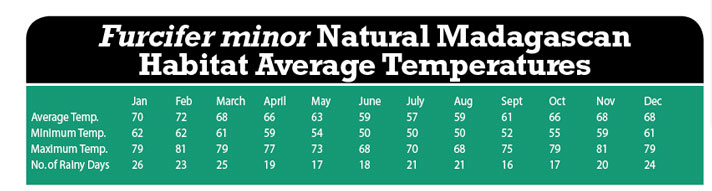

For further guidance in determining temperatures, see the chart above of average temperatures in the Minor’s chameleon’s natural habitat on Madagascar.

Frank J. Payne

Cool-mist humidifiers are being used with Furcifer minor with increasing frequency.

Proper Minor’s Chameleon Hydration

Hydration is one of the most important aspects of chameleon husbandry, and it is currently going through a bit of a renaissance in the hobby. The biggest problem with humidity and chameleon keeping is that the majority of the species being kept, including F. minor, are from high-humidity regions, and replicating that high humidity indoors can be challenging. For years, successful chameleon keepers have gotten around this by heavily misting their animals several times a day. This would provide a temporary spike in humidity and allow the animals to drink from the accumulated water droplets on the leaves of plants inside their enclosures. Most keepers, myself included would only mist their animals during the day, while they were awake and could drink, allowing the enclosure to dry out during the night.

Frank J. Payne

Proper hydration is paramount when keeping this rare chameleon.

While this strategy certainly does work, it goes against natural humidity patterns and may not be ideal. In many tropical environments, atmospheric humidity spikes at night and dries out during the day. This happens even during the “dry season” when rain may not occur for days or weeks. It has been noted by multiple observers that chameleons in the wild often do not drink during the day when it rains, and that they remain well hydrated even during the dryer portions of the year. The hypothesis is that the chameleons are breathing in a substantial amount of atmospheric water vapor during the night, keeping them well hydrated. This high nighttime humidity is often not replicated in captivity, and dehydrated chameleons are commonly seen.

Many keepers are now instituting a more natural hydration scheme utilizing cool-mist humidifiers to direct moisture-laden air into a chameleon’s enclosure during the night and early morning hours. If you have just one chameleon and one enclosure, the cool mist can simply be pointed directly into the enclosure. If you have multiple enclosures, some method of routing the fog into them via piping or tubing will have to be incorporated. After fogging for the majority of the night, the enclosure should then be allowed to dry out for most of the day, as it would in nature, to prevent water stagnation and pathogen proliferation.

Using this method while still incorporating several misting sessions during the day will allow a chameleon to stay hydrated 24 hours a day. Even though this new hydration scheme is still in the early stages of large-scale use, there are many successful keepers, including myself, who have observed positive results from incorporating night-time fogging into their care regimen. The most important consideration when using this method is to make sure that the enclosure does dry out during the warmer portions of the day. A constantly wet environment can lead to your chameleon experiencing a host of health problems.

Lizard Food: the Minors Chameleon

Minor’s chameleons are exclusively insectivorous, and you should provide them a variety of feeder insects that have been properly gut loaded and supplemented. My subadult and adult Minor’s are primarily fed crickets. I also occasionally feed them Turkistan roaches, bean beetles and fruit flies. Crickets are allowed to roam freely in the enclosures to entice chameleons to hunt for their prey. Roaches are placed in an elevated feeding cup so they don’t hide in the enclosure. Because they don’t move very much inside the feeding cup, Dubia roaches are often ignored by my chameleons. Smaller feeder insects, like bean beetles and fruit flies, are often initially overlooked by the adult chameleons, but it is very natural for chameleons of all ages to eat many small insects throughout the day as opposed to a few larger ones periodically.

How to Build Your Own Chameleon Lizard Cage

Crickets and roaches should be properly gut loaded before being offered to chameleons. I feed my insects a variety of greens, fruits and vegetables. Often, I use leftover produce from my own fridge that is starting to go bad. I commonly use kale, dandelion greens, collard greens, carrots, sweet potatoes, apples and bananas.

I dust my feeder insects with Repashy Calcium Plus powder supplement. Juvenile and male chameleons get insects dusted with the supplement powder at every feeding. Females can be more prone to oversupplementation, which is often expressed as edema (swelling of the neck region), so are supplemented every other feeding.

My juvenile Minor’s chameleons are fed every day as much as they will consume. Be careful not to add too many insects; you don’t want chameleons that are overwhelmed with insects crawling all over them. Adult animals are fed every other day.

I have never encountered an obese male Minor’s chameleon, and I allow them to regulate how much they want to eat. On the other hand, female Minor’s are very prone to obesity and their food intake should be carefully monitored. An obese female is much more prone to deadly health issues associated with egg production and laying (more on that in the breeding section). A healthy chameleon should not have tail bones visible. The skin should be smooth and flush, and the eyes full, not sunken, though they also should not be overly round or bulging. It can take some practice, but continuously monitoring and adjusting food intake is something that must be considered when working with females of this species.

Breeding the Minor’s Chameleon

Minor’s chameleons can be prolific breeders under ideal conditions. Both males and females are usually ready to mate for the first time when they’re 6 to 9 months old. Females signal their readiness to mate by developing red and blue dots on their flanks, as well as a similar red coloration on the head. Mature males will rarely turn down an opportunity to mate.

Frank J. Payne

A pair of the author’s Minor’s chameleons exhibiting mating behavior.

If you suspect a female is ready, you can place a pair together. If she is receptive then she will stay softly colored, not move much, and barely react to the male. If she is not ready to mate, she will puff up with her mouth open, and possibly lunge at the male to repel him. Unreceptive females should be removed right away, and you can try placing the pair together again after a few days.

If the female is receptive, the male will head bob and mating usually begins quickly. Copulation lasts anywhere from five to 30 minutes. Sometimes one mating is all a female will accept before becoming unreceptive and aggressive toward the male. Other times, they will mate several days in a row before she’s had enough. I always separate them when I am not present to watch, as F. minor can be an aggressive species and individuals can cause real harm to each other.

Frank J. Payne

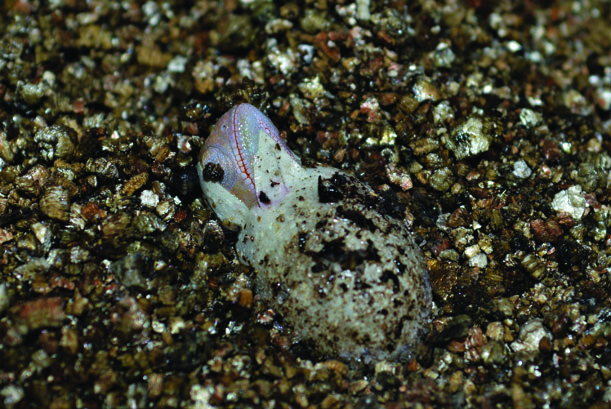

Hatchling Minor’s chameleon.

Achieving successful egg laying can be the most challenging aspect when breeding Minor’s. From talking with other breeders, the biggest problem with this species is females retaining eggs and becoming egg-bound, a fatal condition. Based off my own experience, I have not found this to be a problem as long as the female is kept in proper condition.

As mentioned, feeding female Minor’s as much as they will eat will quickly lead to obesity, and this will result in egg-laying complications. Keeping a female well fed but athletic will result in a healthy female and properly deposited eggs. Between 14 and 35 days after breeding, the female will be ready to lay her eggs. A day or two before egg laying, she will usually stop eating. This is when I will place her in the laying box. I use a 15-gallon, black plastic trash can as an egg-laying site, with a 20 to 40-watt heat light placed on the top. The inside of the container has a 6 to 8-inch layer of a 50/50 mixture of sand and organic potting soil. The key to getting the female to dig and bury her eggs is to have the soil at the appropriate moisture level. It should be very wet, but without standing water. Whenever one of my females refused to dig, it was because the soil was too dry.

I will leave the female in the egg-laying container all day when the lights are on and return her to her terrarium at night. The next morning, I will water her heavily and offer food. After a drink, she goes back in the container. This is repeated until she lays the eggs. Even if she does not bury her eggs and instead scatters them on the surface, there is still a good chance of saving the eggs as long as they are found quickly, before they dessicate. I have had clutches comprised of seven to 18 eggs.

Eggs are incubated in lightly moistened vermiculite. Thirty grams of purified water are added to 30 grams of vermiculite in a 16-ounce deli cup. No holes are used in the deli cup. Eggs are incubated at 72 degrees for 45 days, after which the incubation temperature is lowered to 60 degrees for another 45 days. After 45 days of diapause, the eggs are again incubated at 72 degrees for the duration of incubation. In order to achieve these temperatures an incubator that heats and cools is recommended. I have been using incubators made by DVM Exotics for years now with great results. Incubation time is lengthy and averages around nine months.

Frank J. Payne

Baby Minor’s chameleon.

Hatchling care is identical to that of the adults, except on a smaller scale. Even hatchlings are very aggressive toward conspecifics and should be housed individually in smaller enclosures. Food items include fruit flies, bean beetles and pinhead crickets. Hatchling Minor’s chameleons will grow rapidly with appropriate care and be nearing adult size in as little as six months.

Minor’s chameleons, especially females, are able to express some of the most beautiful colors and patterns in the animal kingdom. For the intermediate to more advanced herpetoculturist, this species is a perfect breeding project as captive-bred individuals are relatively hardy.

As mentioned, F. minor is still very rare in captivity, so finding some may be the biggest challenge. There are only a handful of people working with them in the U.S., and most people that have them only have a pair or two. I was lucky enough to acquire the largest and most diverse breeding group of this species in the country, and I have been fortunate enough to achieve positive breeding results. At the time of this writing I am incubating many clutches from multiple pairs that should be hatching throughout 2018 and 2019. I hope to be able to offer them to the herpetocultural community as early as late 2018.

Frank J. Payne is a biology teacher, former senior herpetology keeper and private reptile breeder. He has been keeping and breeding reptiles personally for over 20 years. As a senior AZA herpetology keeper, he worked with more than 100 species of reptiles and amphibians, many of which were threatened or endangered. As a zookeeper, he traveled the country with live animal exhibits, and he often appeared on television shows, including “Late Show with David Letterman.” Visit him online at livingartbyfrankpayne.com.