Metoposaurus diagnosticus burrowed during conditions when water was scarce.

Metoposaurus diagnosticus, a giant amphibian that lived more than 200 million years ago needed water in order to survive but burrowed into the earth when water was scarce, according to scientists Dorota Konietzko-Meier of the University of Opole, Poland and the University of Bonn, Germany, and P. Martin Sander of the University of Bonn. Konietzko-Meier and Sander interpreted the behavior and published their findings in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

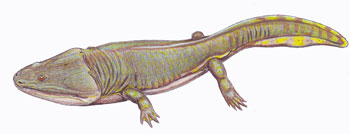

Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikimedia

Metoposaurus diagnosticus

The scientists examined the structure of the skeleton of Metoposaurus, which grew to 10 feet in length and weighed 1000 pounds, and the microscopic structure of its bones and concluded that the amphibian's broad flat head and arm bones, wide hands, and large tail, swam in ephemeral lakes during the wet season and used its head and forearms to burrow into and under the ground during the dry season.

To confirm, the scientists examined cross-sections of the amphibian's bones, in search of annuli, which are the animal's growth rings. They determined that a band of light and a band of dark annuli was one year of growth. They then compared the annuli with other early amphibians in which the annulus feature a broad zone of rapid growth signifying the wet season with a thin band of slow growth during the dry season, and found that the annuli of Metoposaurus diagnosticus showed a period of slow growth during the wet season followed by no growth during the dry season.

"The histology of Metoposaurus long bones seems to be unique. In our interpretation it corresponds to the two-seasonal climate with a short, more favorable wet season and a long dry part of the year when life conditions were worse,” said lead author Dorota Konietzo-Meier.