Though the teeming reefs of Komodo may be sparklingly rich, it is without a doubt that the star attraction of this region of Indonesia is the Komodo dragon.

As a scuba diving instructor, Komodo National Park, in Flores, Indonesia has always been in my top places to dive in the world — as it is on virtually every diver’s bucket list. The park has a rich marine ecosystem, mostly due to the strong current flows coming from both the Pacific and Indian Oceans; with crystal clear visibility all year round.

I’ve visited Komodo many times before, but when a group of friends asked me to join them on a chartered boat for six nights aboard a local Indonesian ‘Phinisi’ liveaboard for a week of scuba diving and cruising, I had no choice but to say yes to visiting this UNESCO Heritage site once more! Diving safari itineraries mainly cater to scuba diving, but it is without question that at least half a day is scheduled to see the most remarkable inhabitant of the park, Varanus komodoensis, otherwise known as the Komodo dragon. Known to be the biggest lizard in the world, it is found no where else in the wild, and is Indonesia’s national animal.

Komodo Dragon Reclassified As Endangered Species

Komodo Dragons Threatened By Rising Sea Levels And A Warming Planet, Scientists Say

Komodo Dragons Conceived At Chattanooga Zoo Via Parthenogenesis

On the third morning of our trip, we woke up being the only boat anchored right next to Komodo Island for a morning schedule to see the dragons. The backdrop behind the nearby ranger station were caramel-colored hills of dry savanna, with pockets of thorny green vegetation and bush-like trees. The sandy beach by the station was a brilliant white, and the turquoise water reflected the morning sunlight like glass. Unquestionably, in all the years I’ve lived in the country, the landscape here is one of the most dramatic in the entire Indonesian archipelago.

Komodo dragons are the largest lizard in the world.

As we approached the beach on our rubber boat, two local rangers dressed in proper ‘Naturalist Guide’ green uniforms approached us, and led us in the opposite direction from where a pre-adult Komodo dragon was already basking, 20 meters away. The guide shared that the chances of us running into them are higher earlier in the day when they sunbathe to facilitate food digestion. And by midday, they would disappear to seek shelter from the heat, in the thick bushes of the island.

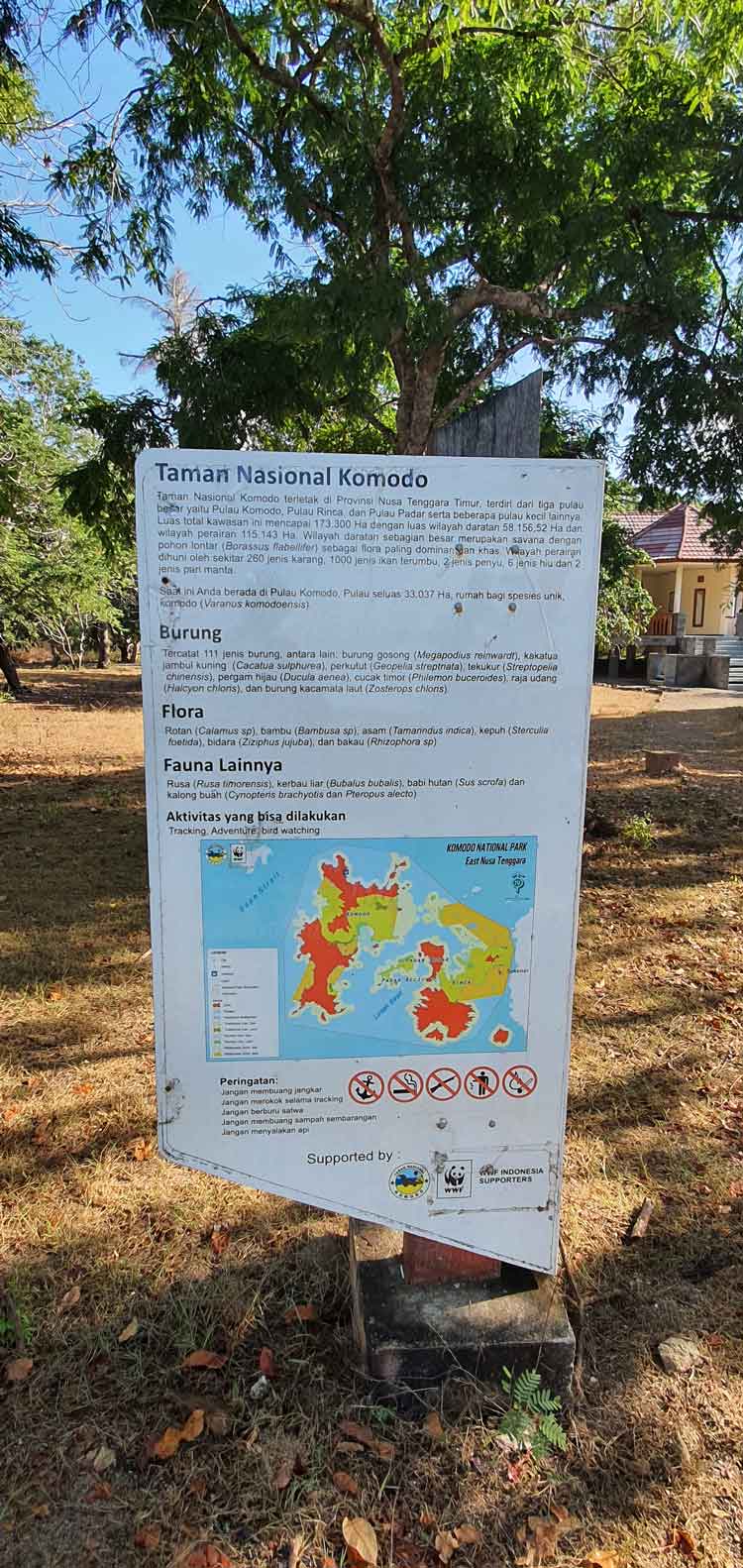

A giant Komodo dragon statue marks the entrance of the trails, where a huge map of the area is posted and where it is safest to take a selfie without having to risk losing a limb. Our guide starts narrating the park rules: no trekking without a ranger, no trash left behind, no smoking, and no harassing or feeding of any animal in the park. It is also best not to bring any food, (especially meat products) as the dragons’ primary food detector is their sense of smell.

“We had a small bush fire incident last year, when a tourist threw a cigarette butt! Luckily no animals or dragons were hurt, but you know, a tree here takes 10 years to grow!”, the guide said. For safety reasons, two guides need to accompany each walking group, one who leads and one at the back. Dragons are not to be taken lightly, they can grow up to 9 feet long, weigh over a hundred pounds and eat up to 80 percent of their own body weight in one sitting. Our guide then presents us with three walking trail options – First, a 40-minute, 2km track, another 60-minute, 2.8km track; and lastly, a 120-minute, 4.3km track.

Komodo dragons are found no where else in the wild except in Komodo National park. Photo by Anne Astorga

The trails here on Komodo Island are an easy walk, flat ground all throughout, and suitable for all ages. But because we had to head back to the boat for a mid day dive, we opted for the shortest route. Regardless of whichever trail you choose, the ‘Komodo Dragon’ trekking fee day pass stays the same, which is only IDR 175,000 / USD $12. Tipping the rangers is highly recommended. They share a wealth of information about the dragons and animals in the park, and they can save you from the dragons who may decide to charge you at 20km/hr top speed!

As we started walking the bushy trail, we were led to a huge muddy clearance in the forest, somewhat looking like a water hole in Africa, where a pond was dug out of the clay-like soil. It was clearly man-made, also providing an area for the wild boars and Timor deer to drink from, and in aiding the Komodo dragons in their hunt for food. As there are only slightly more than 1,500 individual lizards left on Komodo Island, and 1,300+ in Rinca Island, the rangers are now doing everything possible in ensuring they provide ‘easier’ ambush foraging opportunities for these endangered lizards. They used to attract them with goat for tourism purposes, but this has no longer been a practice for years.

An adult Komodo dragon at rest. Photo by Anne Astorga

The rangers carried long wooden sticks, as the park also provides refuge for many other terrestrial species such as the Timor deer, water buffalo, wild boar, forest fowls, endemic rats – all prey for the carnivorous lizard. The sound of birds were all we could hear walking the trail, and we were wary of any rustling sound besides our footsteps as we were told to look out for venomous snakes that inhabit the island – Javan spitting cobra (Naja sputatrix), blue pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris insularis) green viper (Trimeresurus insularis), Russel’s viper (Daboia russelii), all often seen in the early morning. Fortunately, we didn’t step on any!

Can you spot the Komodo dragon? Photo by Anne Astorga

As a tourism location known worldwide, the park receives strong support and resources from the central government of Indonesia and the Komodo dragon is arguably, the country’s best conserved animal. However, a huge chunk of conservation fees come from tourism revenues. Fees are normally collected before a trip by the tour operator you’re with, as these are combined with other fees depending on your planned itinerary. These fees include harbor taxes, boat rental fees, park pass fees, and trekking fees depending on which island you’re on.

Over the years, the local government has utilized these monetary resources in building programs that increase community awareness through engaging local villagers for the sustainable use of natural resources and park conservation. The biggest threat to the dragons is deer poaching, which is the dragon’s main prey, and the rise of population in the area. The species shares the park with about 4,000 people, many of whom supplement their incomes through selling souvenirs to tourists. Zoning programs for visitors and patrolling of reefs from illegal fishing are also implemented to further reduce the impact of tourism on the park.

Stay on the trail. Photo by Anne Astorga

Indonesia closed its borders since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020, and so has Komodo National Park but has reopened again in September 2020 to domestic tourism. Because of the limited number of tourists coming into the park, it has been increasingly difficult for tourist operators based in Labuan Bajo to fill their tours boats, making it more expensive for single travelers, as they would need to charter a whole boat to get around the park. Many of the local tour operators also now pool their guests together to save operating costs, and daily trips to the park are not guaranteed, unless of course, you are willing to charter an entire boat which can cost you from USD $500-5,000 a day.

An average full day trip coming from Labuan Bajo to see the dragons ranges from USD $100 -150 which would include meals, boat costs and park fees. However, with the current COVID conditions, be prepared to double or triple the price depending on the number of slots to fill on a boat. Rinca Island has remained closed since the start of the pandemic to this day, a good opportunity to reduce tourism impact on the more than 1,300 Komodo dragons that inhabit the island. At present, only less than 10 percent of the national park is actually open to the public, so many of the dragons are able to live in Jurassic Park-like conditions. Scuba diving and water activities remain possible everywhere in the park, but visits to islands/beaches which have known lizard populations are prohibited.

Approximately 1,500 Komodo dragons can be found on Komodo Island, with about 1,300 on Rinca Island. Photo by Anne Astorga

We were almost at the end of the trail on the beach and getting quite disappointed to have seen one dragon so far. But then there it was, 30 meters ahead of us on the sand, was this huge stoic looking, almost 8 ft adult basking in the sun, and two more within 50 meters. We took turns getting photographed with this elusive lizard, until eventually it started yawning and flicking his forked tongue. “Hurry start taking a video, he’s going to start walking and move elsewhere”, the guide says. Moments later, he lifted his bowed legs and started strutting in proper lizard king fashion, slow but pompous. His muscular tail dragged on the sand, leaving a distinctive trail until he disappeared in the bushes. Another surprising find on the bottom of a massive tree, was this baby dragon less than a meter long. The guide told me it is about 3-years-old and at this stage, brave enough to wander off from the tree where it spent the first two years of its life, only coming down to drink or feed. Adult dragons are known to also eat smaller members of their own species and sometimes even other adults.

As we exited the trail toward the souvenir section where carved wooden dragons, shirts and memorabilia were sold, I looked out to see that the rangers were still there, keeping a close eye on dragons that may be lurking nearby. I realized and thought to myself how the locals have learned to live alongside these dragons for generations. Locals claim that no dragon has ever claimed a life of a ‘Manggarai’ – the indigenous people of Komodo, and in return, they will do everything to protect their endangered animal that also provides them with their livelihood. Though the teeming reefs of Komodo may be sparklingly rich, it is without a doubt that the star attraction of this region of Indonesia is the Komodo dragon.

Anne Astorga is a writer and dive instructor based in Bali, Indonesia.