Did you know that science still doesn’t know about the tadpoles of more than half of all known frog species?

How well do you know tadpoles? Do you think all frog species go through a tadpole stage as babies? Did you know that science still doesn’t know about the tadpoles of more than half of all known frog species?

According to a paper published in NPJ Biodiversity in 2023, more than 50 percent of all known frog species’ tadpole stages (embryonic/larval) have yet to be described in detail by science. A group of researchers from Argentina and France compiled a dataset containing 7,507 anuran species (frogs and toads) and investigated whether each species’ tadpoles had been described. Responding to an email questionnaire, Florencia Vera Candioti, from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina (Unidad Ejecutora Lillo, CONICET-Fundación Miguel Lillo), and lead author of the paper, says, “More than half of frog species (currently there are ca. 7800 species in total) still have their tadpoles unknown to science.”

Embryos of Pithecopus gonzagai (Hylidae) in their leaf nest

Frogs undergo a thyroid-mediated metamorphosis, an extraordinary process that transforms a tadpole into a frog. Tadpoles (larval stages) are typically vastly different from their adult forms in most biological characteristics. “What we consider a ‘typical tadpole stage’ is a specimen that swims freely, feeds in the water, and has a rounded body, tail, and no forelimbs,” the researchers said. However they point out that tadpoles vary greatly in body structure and ecology. “Many are not typical in a morphological nor functional sense,” they said. “The most unusual among them don’t even look like tadpoles at all [they have four limbs, no gills, no locomotor tail] and develop fully inside eggs. You wouldn’t call them tadpoles.”

Embryos of Dendropsophus haddadi (Hylidae); these tadpoles develop usually in ponds but frogs of some populations have been observed laying eggs within bromeliads. Photo Marcos Dubeux

Since most scientific studies focus on the adult frogs and toads, many larval stages have slipped past scientific scrutiny. The researchers prepared a detailed spreadsheet, listing all known frog species and investigating whether each one’s tadpole had been described; they continually update it with newly described frog species and include recently described tadpoles. They then grouped the tadpoles into various “ecomorphological guilds.” These guilds are based on features such as developmental mode (i.e., whether the tadpoles feed on external sources or not), morphology (physical appearance), microhabitat, and feeding mechanism, with some overlap among features.

Typical pond tadpoles of Boana semilineata (Hylidae). Photo Marcos Dubeux

At the time of publication in 2023, their findings showed that only 3,088 out of 7,507 frog species (41%) had their larval stage described. They also highlighted a geographical imbalance, with the Northern Hemisphere having most of their tadpole fauna already described. Additionally, the study found that endotrophic tadpoles (those that do not feed from external sources) are less studied. The authors reported that, among the 7,507 known species of frogs, at least 2,303 (30% of all anurans) are suspected to be endotrophic, yet tadpoles of only 226 (3%) had been described. Among these, the least is known about direct-developing species, frogs that lay terrestrial eggs and skip a free-living, typical tadpole phase.

They noted a disparity in the amount of information on frog tadpoles from different regions of the world. More research has been conducted in certain areas, while others—particularly biodiverse regions like the Tropical Andes and New Guinea, which are home to many frogs that bypass the typical tadpole stage—have been studied far less.

Stream, suctorial tadpoles of Corythomantis greening (Hylidae).

“Tadpoles of some frog families are relatively well-known because they have wide distributions, several research groups study them, or they are easy to find and describe,” the researchers said. “Others, however, are not as well-known. They inhabit remote areas or develop in environments so different from ‘typical’ tadpoles—such as within eggs in terrestrial nests—that they may not be accessible to many tadpole specialists.”

“Anyone looking at tadpoles may conclude that they are rather simple animals and not particularly interesting,” said Dr. Richard Wassersug, a long-time tadpole researcher who has authored hundreds of papers on anuran larvae. Wassersug believes that most people—whether biologists or not—likely assume all tadpoles look similar, which discourages the study of the structural variations between them. He added that the remote locations where many anurans reside often make fieldwork physically demanding.

Cane Toad Tadpoles In Australia Cannibalize Younger Tadpoles

“Frogs most often breed during the rainy season in the tropics, which can be an unpleasant and particularly challenging environment for humans,” Wassersug said. He described the difficulties researchers face: frogs may live in thorny plants, and there are threats such as biting insects, land leeches, and other harmful creatures.

“Many of the unknown tadpoles may have very short larval periods and breed in tiny bodies of water, or as the authors note, don’t even have an aquatic larval stage,” Wassersug said. “In sum, finding those ‘yet-to-be-discovered’ embryos and tadpoles remains difficult.”

Typical pond tadpoles of Leptodactylus vastus (Leptodactylidae) still in their foam nest. Photo by Marcos Dubeux

Javier Nori, from the Institute of Animal Diversity and Ecology (CONICET) and the Center for Applied Zoology (National University of Córdoba), Argentina, and one of the paper’s authors, expressed surprise at how many frog species lack detailed tadpole descriptions. “However, regarding the geographic pattern, I was not so surprised. There is a clear link between the development of research systems in different regions and the level of knowledge,” he said.

Preserved tadpole of Phyllodytes gyrinaethes (Hylidae), showing its highly modified morphology (e.g., hoof-like snout, an abdominal sucker, warty tail fin). Photo Florencia Vera Candioti

Similarly, Vera Candioti noted that bridging this gap in tadpole knowledge will be a challenging task requiring more in-depth research. The researchers pointed out that studying tadpoles in remote locations is difficult, which discourages many researchers from pursuing such studies. Additionally, the inherent traits of some frog species make it challenging to locate, collect, and describe them, as they do not always resemble typical tadpoles.

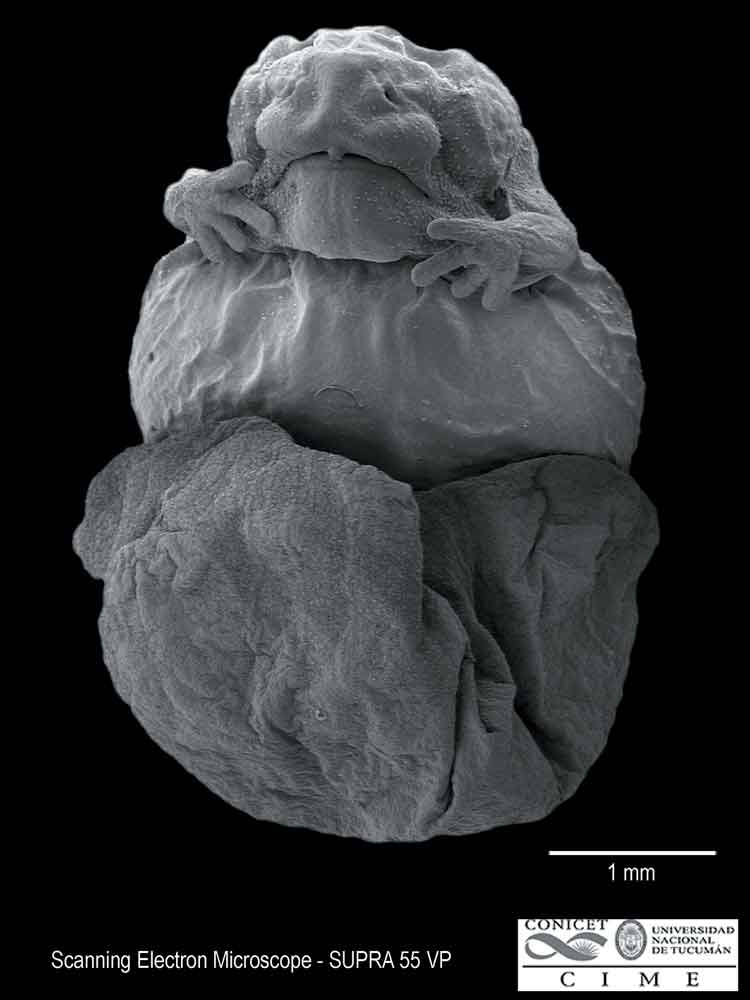

Scanning electron micrograph of a direct-developing embryo of Oreobates berdemenos (Strabomantidae), showing its highly modified morphology (e.g., forelimb exposed, mushroom-like tail enveloping half body). Photo Florencia Vera Candioti

Dr. Ameal Borzee, co-chair of the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (ASG), attributes the lack of funding for amphibian conservation as a key reason for the insufficient knowledge of anuran tadpoles worldwide. The ASG supports various activities aimed at amphibian conservation on a global scale. Dr. Borzee explained that tadpoles are influenced by two primary factors: hydroperiod and temperature—both of which are increasingly disrupted by climate change. He also noted that species with direct development are at risk due to changing humidity patterns.

“Field studies are critical for obtaining this type of information, but unfortunately, they are hard to fund,” he said. Borzee stressed that while studying tadpoles may seem tedious, it is essential for building the foundation of amphibian research. “Perseverance is key, and anyone interested in contributing to amphibian conservation can reach out to the ASG for support.”

Dr. Wassersug further pointed out that in addition to studying the taxonomy of frog tadpoles, equal attention should be given to understanding their ecology. “It’s not just about finding and collecting tadpoles from more species,” he said. Wassersug agrees with the researchers’ point that more effort should be directed at discovering the yet-unknown tadpole species. “I don’t disagree, but I would add that we also need to do more than just collect tadpoles and determine their taxonomic relationships—we must also understand their precise ecological needs.”