Students at Weston High School in Massachusetts captive breed and then release Blanding's turtles.

Herping in the suburbs of Massachusetts rarely yields diverse finds. Garter snakes shelter in the woods; leopard, wood, and green frogs lurk in the waters, and toads conceal themselves in the brush and soil. Surprisingly, turtles are the among the rarer, more elusive finds, especially those that aren’t painted or red-eared. This is a state where even the testudines are secretive. Well camouflaged, they throw themselves back into the water at the slightest notice of detection. The only exception is during breeding season. In the spring and summer, they make perilous journeys across roads, finally allowing us a welcome glimpse into their hidden lives.

Emma Hsiao

Emma Hsiao helped release captive-bred Blanding's turtles.

While herping, I’ve only ever encountered one turtle that was deemed uncommon (or more so than typical pond turtles). She was a decently sized snapper. Rumors had circulated around about the snapper that inhabited the streams and ponds criss-crossing the school property. Some even claimed that she had come up to the school courtyard to lay eggs. Fellow students would post their sightings onto social media, excitedly recounting their “face-to-face encounter with nature.” Knowing that this is the same school where kids stomp frogs to death, I am relieved to say that no one has tried to get too close to that turtle (yet). I had stumbled across that snapper by accident, taking a stroll around the streams during an outdoor gym class. An unfamiliar shape on the periphery of the pond caught my eye. There she laid, under one of the concrete pond supports. I remember the smooth dark scutes, massive forearm claws, and the pointed head. She was easily over a foot long. I didn’t have my phone with me, but a friend snapped a photo of her. We didn’t dare venture closer, due to the slippery terrain and the fear that we would scare the turtle away.

Though Massachusetts is home to a limited selection of herps, especially in the semi-developed areas, it didn’t stop me from trying to learn about as many as possible. As a freshman, I started a herp log, a binder full of information and drawings of the native and invasive species. Of course, this spurred the need to research, and the school librarians soon became familiar with the little Asian girl that always came back to check out that reptile book one more time. In fact, I had borrowed their decades old, practically untouched copy of the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians so many times, that on the 14th renewal in a row, they insisted I keep it. I’ve taken to carrying that field guide around at all times, which led my peers to lovingly nickname me “the Herpie.”

In those pages, there was a particular emydid that had fascinated me. It was described in the field guide as “5-10.5 inches. Bright-yellow chin and throat quickly identify basking specimens. Smooth helmet-shaped carapace is black… Plastron hinged.” Apparently they naturally occurred in Massachusetts as a “separate population,” but I’ve yet to see one, even during breeding season. The Blanding’s turtle, Emydoidea blandingii, upon further research, was found to be listed as “Special Concern” in my state. Threats to the Blanding’s turtle are habitat loss, human activity, and roads.

EMMA HSIAO

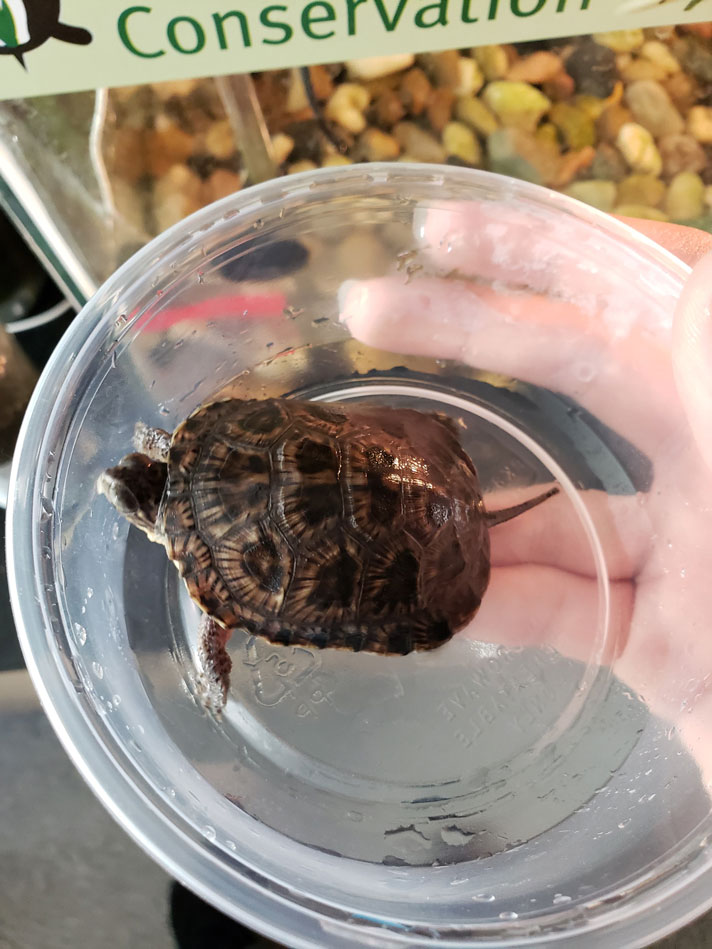

The turtles were first acclimated in enclosures in the waters that they were to be released, to expose them to the prey they would eat.

There are only a few populations of Blanding’s turtles left in Massachusetts. Most of which are concentrated in protected wetlands, and are monitored by wildlife organizations like Grassroots Wildlife Conservation. Grassroots works on maintaining stable populations of native herps through head-starting the hatchlings, reintroducing them to their natural habitat, and monitoring their progress. They locate clutches, and incubate the eggs so that the hatch rate is higher than in the wild. Then, some of the hatchlings are sent to classrooms, where during the school year, students partake in rearing the them. This allows the turtles the opportunity to grow over the winter and get to a size where they could have a better chance of surviving in the wild. At my high school, sophomore biology classes get to work with them and create a year-long project about monitoring their growth.

In June 2018, I had the chance to release the Blanding’s turtles the sophomores at the time had raised. They were to be reintroduced at Great Meadows Wildlife Reserve in Concord. These turtles had started out just barely bigger than a quarter, and now they were nearly four inches long. They were first allowed to be acclimated in enclosures in the water. These floating cages exposed them to the aquatic invertebrates and fish they would need to prey upon. This was crucial as the classroom aquariums they were raised in offered shallow waters, bountiful immobile food, and no predators. These were ideal nurseries, but a stark contrast to the wetlands they would soon inhabit. Once they were released, they had a chance to be recaptured in one of the floating turtle traps in the wetlands. Researchers would then check the turtle’s unique shell notch number and measure mass, length, and make any other observations. While visiting with my school, we pulled an eight-inch male Blanding’s out of one of the traps. He was around 10 years old, and was missing his left forearm. The researcher said that he was likely raised in a classroom in the early 2000’s.

This year, as 10th graders, some other students and I were given the opportunity to work with the turtles in biology class. A member of Grassroots came to my school, gave a presentation, and brought four hatchlings, two for each classroom. Since then, a few other students and I have used our free blocks and come in before school or during lunch to feed, mass, and measure the turtles. The original pair that my class had taken were both good feeders. However, the other class had less luck, and one of their turtles was reluctant to feed. Eventually, we had to take care of theirs too, since they couldn’t get one of them to grow. That particular hatchling proved to be a challenge, as they would hide under the filter or heater during feeding time. The other turtles (kept in the same tank) would often harass them during feeding, so we had to feed them separately. However, the most recent mass and measure shows that the smallest turtle has finally started gaining weight. Three grams isn’t much, but it’s improvement.

Working with turtles from a conservation perspective is a unique experience. When raising them as pets, people aren’t pressured with a deadline or a target size the hatchlings must grow to. Undoubtedly, having experience with casual turtle husbandry is helpful, and has helped me time and time again with handling, reluctant feeders, and cleaning. For example, three years ago, I took in two red-eared sliders from a friend who wished to rehome them. Those turtles taught me how to coax turtles into feeding, keep them calm while massing, and how to hold them steady while handling. My peers were not as prepared, and often asked me for help when trying to calm a squirming hatchling. To be able to apply these otherwise obsolete skills to an impactful cause makes me proud to be “the Herpie.” There aren’t very many opportunities for students to partake in wildlife conservation, but the ones that exist bring a unique experience that inspire young people to look at the world around us in a new way.

Conservation is a story of hope, education, and a vision of a future where the diversity of life is maintained. The Blanding’s turtle holds a unique position in the ecology, their disappearance would be catastrophic, as predator and prey relations must adapt to continue to rebalance the ecosystem. Before there were conservation efforts made for these turtles, they were on the decline due to habitat loss and the roads. Their slow reproductive cycles and vulnerability as hatchlings also made natural recovery difficult. Now, with the help of conservation, Massachusetts is home to the most Blanding’s turtles throughout its range. However, only four populations are known to consist of 50 turtles or more. There is still work to be done, though the results are promising.

Just as the environment has played a role in caring for us and our society, we must also care for nature. Many people, as children, have ventured outdoors and were inspired to learn about the world they saw. Romping in the woods, chasing down butterflies and frogs, and turning over rocks to see what was underneath create experiences that nothing virtual or indoors could ever replicate. Many people, as children, read books about endangered species, were inspired to protect the world they saw, and wondered what they could do to help. Some of them have grown up and worked towards conservation, but others have moved on. Perhaps now, as opportunities present themselves to younger people, they’ll be taken, and empower people to protect the diversity of life no matter what their age is.

Emma Hsiao is a student at Weston High School in Massachusetts. She has a passion for herpetology and the conservation of endangered species. Her work is featured at: https://emmahsiao.me