The most common lizard we found, as I expected, was the pelagic gecko.

Friday, April 27, 1990

That morning I woke early. Not because I was especially good at waking early, as I was still dog-tired from the day before, but because I was woken early for the same reason everyone within two kilometers was awake.

In the yard in front of the big house at Kaviak was WWII bomb — a big rusty one, hanging from a gantry. I had noticed it the day before. Clearly it was defused and had its explosive charge removed, which was just as well because every morning, as the light was just breaking, it was repeatedly hit hard, very hard, with a hammer. It didn’t matter how deeply you slept; only the dead could sleep through that!

I quickly rose, showered, dressed and went to the house for breakfast. As I walked up the drive, I saw plantation workers converging from all directions, grinning, smiling and laughing. Several of my boys from the day before were there, and they shouted salutations and good mornings. I passed Roger coming out as I was going in. “You’re late,” was his friendly morning welcome.

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

Direct-breeding frog (Platymantis papuensis)

I hurriedly ate and rushed back out to join the throng, just in time to see teams of workers, men and women, drawing bush knives from the store to kutim gras (clear vegetation in the plantation). These barefoot workers are often the ones bitten by the nocturnal small-eyed snakes. They disturb the sleeping snakes that did not return to the husk piles, often with tragic results. Kaviak tried supplying rubber boots to the workers some years previously, but it was a failed experiment with boots disappearing and more boots being requested on an almost daily basis. Many workers, used to walking barefoot and having developed broad feet, apparently found the boots restrictive anyway.

Wagga was busy organizing a group of about 30 men into three teams as Roger strolled over. “I’m giving you 30 men today, and I’ve told Wagga where to take you. That should do it. Come back with a snake today,” he said briskly as he strode off to his office.

Wagga, the 30 happily chattering workers and I climbed aboard a single tractor and trailer and set off. Several of the men perched precariously on the coupling between the two units; clearly “health and safety at work” was not a concept that had found its way to Karkar Island. All the way the men smoked, laughed and talked. Snake hunting was probably more exciting and much less strenuous than a normal day at work.

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

Jakati River skink (Emoia jakati)

There was an added bonus too: The word had gone out that I was awarding 10 kina (comparable to $10) to anybody who sighted (but did not capture) a venomous snake that I was able to confirm — regardless of whether I succeeded or failed to catch it. I was anxious to discourage workers from trying to catch anything dangerous themselves and getting bit in the process. No matter how desperate I was to find small-eyed snakes, I would rather return to the mainland empty-handed then leave in the knowledge that my project had caused an unnecessary snakebite on the island.

The drive to the selected search area was longer this morning. The track left the lower, flatter part of the plantation, and the tractor and trailer chugged and laboured up the steep tracks of the lower slopes of Mt. Uluman. The area was scoured by deep, overgrown, volcanic gullies known as “barats.” They could become raging torrents when the volcano received heavy rain, which was regularly. Eventually we came to a stop. Wagga ordered the men off and organized the three teams.

I suggested we select three husk piles within earshot so I could respond the moment a snake was sighted. I liked the look of the steep, densely vegetated barats so we set one team to work halfway down the slope while the other two were to work on the level nearby.

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

Common ground snake (Stegonotus parvus)

Then I noticed that hidden in among the trailer-full of plantation workers were several children. Had I known they were there when we set off, I would have left them behind — small children and venomous snake hunts don’t mix. They were keen to join in the fun, but I wanted to keep them out of trouble. I gave them a couple of very important jobs: to carry my day sack and wear my slouch hat. I needed to know where these important items were at all times, and the two youngsters seemed more than pleased with their new jobs. A handful of sweets sealed their wages. They smiled broadly as they followed me up and down the trail as I watched the men working to clear the kudzu vine and begin excavating the first husk piles of the day.

I kept busy with three husk piles and 30 pairs of eyes. During the day, we had a steady stream of interesting creatures. For invertebrates, we saw two land crabs, two large mygalomorph spiders, several large wolf spiders, one centipede, dozens of millipedes, a few scorpions and whipscorpions (amblypygids). However, the most interesting invertebrates we found were not actually collected in the husk piles but in a rotten log the boys were breaking up to move out of the way. They turned up two velvet worms (Paraperipatus sp.), members of a curious group, Onchophora, once considered a link between the annelids and the arthropods. I immediately recognized the importance of these tiny drab caterpillar-like creatures, but at the time I was not aware I had just collected only the 15th and 16th specimens known from New Guinea.

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

New Guinea small-eyed snake (Micropechis ikaheka)

One might think that a volcanic island, with little or no standing water, might not be an ideal place to find amphibians. But as usual, nature finds a way. The husk pile searches turned up several Papuan direct-breeding frogs (Platymantis papuensis), a species that goes directly from the egg to froglet, omitting a free-swimming tadpole stage and the need for freshwater. In similar habitats on Caribbean islands, there are several leptodactylid frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus that have adopted the same reproductive strategy.

The most common lizard we found, as I expected, was the pelagic gecko. We turned up so many I could not count them, but the boys also called me to a scattering of skinks. Initially these were long-legged, fast-running brown four-fingered skink (Carlia fusca) and various emoids: Jakati River skink (Emoia jakati), dusky skink (E. obscura) and pale-headed skink (E. pallidiceps). As the men worked deeper into the husk piles, the skink fauna changed to a more semi-fossorial type dominated by the diverse genus Sphenomorphus, represented by the elongate-bodied, reduced-limbed, small-eyed fasciatus-group; the Solomons wedge skink (S. solomonis); Wolf’s wedge skink (S. cf. wolfi); and the stout, square-bodied, strong-limbed, large-eyed variegatus-group, such as the Jobi skink (S. jobiensis).

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

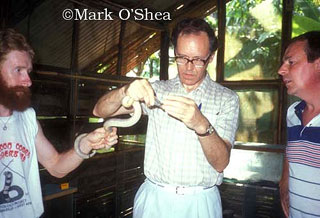

From left to right: Mark O'Shea, Prof. David A.Warrell (Oxford University) milking small-eyed snake, and Prof R.David G.Theakston (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine) at C.R.I.

I was very pleased to find even more crocodile skinks (Tribolonotus gracilis). I caught, measured and documented each one. I remember one specimen in particular. It was an egg. (A female T. gracilis lays a single egg, measuring approximately 26 by 10 mm, with a roughly striated shell.) I picked one of these up from inside a coconut husk handed to me. I placed the egg on the palm of my hand, but as I examined it closely it did an amazing thing. It jumped two to three times in rapid succession, like a Mexican jumping bean, and then to my total surprise, it hatched right there in the palm of my hand. The eggs erupted and spilled out a tiny hatchling crocodile skink. I wondered what the odds were of finding an egg at the moment of hatching.

We also found some of the larger skinks, including a juvenile blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua gigas) and three brown sheen skinks (Eugongylus rufescens). This last is a very interesting species; it is one of two Eugongylus species reported for New Guinea. The other species, the white-striped sheen skink (E. albofasciatus), has been reported for Karkar Island, but all the specimens I have examined — on the island and the mainland — have been E. rufescens. I have my doubts that E. albofasciatus is present. The sheen skink is a predator that feeds on large invertebrates and smaller skinks.

Just before lunchtime (I brought sandwiches this time, just in case), I was called to a husk pile and captured a juvenile mangrove monitor lizard (Varanus indicus). I am sure the microhabitat provides everything a young monitor could desire: sanctuary, humidity, ample prey — so much easier than risking it with Rosa Middleton’s chickens.

Snakes were slow in appearing, but the three teams turned up a few. There would be a shout, and I would run over to where the guys had backed off. Following their pointed fingers and excited chatter, I would find the hiding place of a serpent in the shadows. In this way I caught common ground snake (Stegonotus parvus), two brown treesnakes, a couple more ground boas and eventually my quarry, three New Guinea small-eyed snakes (Micropechis ikaheka). Each measured approximately 3 feet long.

When the plantation workers discovered a small-eyed snake, the hullabaloo was much louder and excited than that caused by the discovery of a mere boa or treesnake. I am not sure if the excitement was caused by being in close proximity to a dangerous snake or the 10 kina it represented for the eagle-eyes who saw it first.

“Posin snek, posin snek, em i stap insait.” (Poisonous snake, he’s in there.)

Even though the three snakes were only 3 feet long, they were still difficult snakes to capture. More like kraits (Bungarus spp.) than cobras, they twisted and tried to bite, but they were truly spectacular to look at. Small-eyed snakes have white to yellow-white bodies with brown to red-brown bands, which are more numerous and frequent toward the tail. The tail is completely grey-brown; the cobra-like head is grey and rounded, with tiny eyes.

With three small-eyed snakes and 30 kina poorer, I returned to the Kaviak plantation offices early so I could pack for my flight out early the next morning. The boys in the teams were chattering, laughing and singing. I was sure they enjoyed the day as much as I had. Wagga stood bolt upright in the front of the trailer like the commander of a victorious army. I sat on the side of the trailer running through the events of the day and how fortunate I considered myself to have obtained not one but three small-eyed snakes in readiness for the visit by Davids, Warrell, Theakston and Lalloo in a few days. I was lost in thought when we reached the station offices and did not hear my name when first called. Wagga brought me out of my private thoughts.

Photo Credit: Mark O'Shea

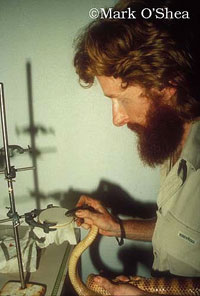

Mark O'Shea milking a New Guinea small-eyed snake.

I followed him to where a group of plantation workers stood in a circle near one of the large buildings. In the centre of the circle was a large ground boa, one of the largest I have yet seen, almost 3 feet long in length. Unlike the sleepy snakes up in the plantation proper, this fellow was up for it, striking wildly and aggressively at the ring of men that surrounded it. My credibility went up several notches when I breezed in and swept the boa up without getting bitten.

One useful rule to remember when catching snakes that people have been waiting for you to come and collect: Don’t just bag it then, say thanks and walk off; that is anti-climactic. Instead, pick the snake up, handle it, show it to the audience and try to tell them something about it. “Dispela snek, em i nogat posin, em i gutpela, em kaikai rat.” (This snake isn’t venomous; he’s a good snake that eats rats.) That way, the next time they find a snake, you can be sure they will call you instead of simply killing it.

That evening, as I ate dinner contentedly with Roger and Rosa, the houseboy came in and spoke to Roger. It seemed someone was reporting a snake just outside the compound. Roger and I left the table, and we strode across the lawn to another huddle of workers. They parted to allow me access, and I saw an adult brown treesnake coiled in a defensive posture. “Ah, an egg python,” Roger said.

I flew out to the mainland the next morning with my valuable cargo of venomous snakes. Even as I left, I thought I would be coming back to Karkar Island. I was not wrong. I returned for a longer stay a few weeks later and caught another 12 small-eyed snakes ranging from juveniles to an impressive 5-footer. Karkar was also on my itinerary on later field trips to Papua New Guinea in 1992-93 and 1993-94. When we filmed the second series of O’Shea’s Big Adventure in Australasia and the Pacific, I included a film trip to Karkar entitled “Magic Man.”

To discover more about Mark O'Shea's adventures, visit his website at www.markoshea.tv