Several years ago I landed a job as the guy that incubates, hatches, and raises Eastern Indigo snakes (Drymarchon couperi) for a head start and releas

Several years ago I landed a job as the guy that incubates, hatches, and raises Eastern Indigo snakes (Drymarchon couperi) for a head start and release program in the state of Alabama. It was by far the most rewarding work I’ve ever done. Not only did I get to work with (in my opinion) the most bad ass snake on this side of the world, but I also helped conserve it in the wild. I was a small spoke on a large wheel of a massive project involving Auburn University, Zoo Atlanta, the Orianne Society, and several state and federal government agencies.

Indigo Snake Information

- Breeding the Eastern Indigo Snake

- Climbing A Tree to Save an Eastern Indigo Snake

- Drymarchon couperi

The Eastern indigo snake is one of the largest snakes in North America. It can reach almost three meters in length. They are non-venomous, with a generalist diet. This means they eat almost any prey item that can fit in their mouths. They, unlike many non-venomous snakes in the pet trade, are not constrictors. The way they kill their prey is brute force. An adult Indigo snake can kill a large Eastern diamondback rattler by crushing its head and swallowing it whole. Most of their diet as juvenile snakes is made up of other snakes, rodents, and anurans (frogs and toads). As adults they also eat a lot of baby gopher tortoises.

The snakes once lived in southern Alabama but were extirpated (locally extinct) due to habitat loss, rattlesnake roundups (burrow gassing), and collection for the pet trade. They live in gopher tortoise burrows in the long-leaf pine forests of Florida, Georgia, and finally, once again, Alabama. In the time I worked on the project we hatched and raised close to 200 snakes for the conservation effort. My small part involved incubation of the eggs, and feeding the hatchlings for several months before sending them to Zoo Atlanta where they were head-started for a couple years prior to release.

I had already been working with reptiles for many years as a hobbyist and professionally as a zookeeper. I didn’t know any of the ways of science but, like many of you, I knew reptile husbandry. So it was a new and confusing adventure. While we incubated the eggs and fed the little beasties I learned the importance of recording data. Luckily some intelligent people were around to help me out and point me in the right direction.

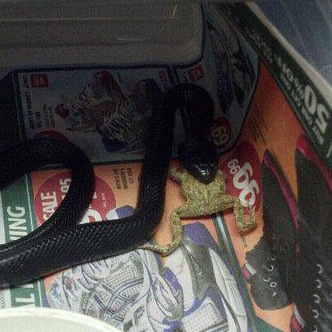

We recorded the weight, species, and number of prey items for every single meal for every single snake over several years. Since the snakes were to be released into the wild, we decided it would be best to feed them a diet as close to what they would eat in the wild as possible. They ate everything and anything, including: rodents, snakes, frogs, toads, baby quail, several species of fish, skinks, anoles, fence lizards, and even occasionally hatchling turtles.

mike wines

An indigo snake guarding its eggs.

As many of you know all too well, baby snakes can be finicky. Some refused most species of prey and only liked one particular flavor. Others would gladly gobble down anything that wiggled, including the occasional unlucky finger. So after several years of gathering data, and raising the shiny little monsters, I had a huge pile of information. I wanted to do something with it. The herpetology professor at Auburn University (War Eagle) offered me a position in his lab to obtain a master’s degree. I had to learn how to science. So I took classes and learned statistics and cried and drank a lot of beer and asked a lot of questions. Somehow at the end of it I had written a thesis (which was just published in Zoo Biology – referenced at the end if you want to suffer through reading it).

In all that sciencing, we figured out that the snakes that ate a more diverse diet grew faster than those that ate a less diverse diet although they had the same amount of food by weight (Wines et al. 2015). Yes, I just referenced my own scientific paper in an article for ReptilesMagazine.com Let me take a second to have a nerd moment. . . Thank you. That felt good. We also figured out the proper temperature to incubate the eggs at. I will save this for another article in the near future. Did I just leave you with the geekiest cliff-hanger ever?

Now, back to the important stuff, what does this diet diversity information mean for your husbandry practices? Should you change your snake’s diet? The simple answer is if so, probably not much. The Indigo snakes were being raised to be released. Your snakes will hopefully never be released and will live their lives in captivity. They don’t need to eat a natural diet because they aren’t going to live in nature. Many of you have raised snakes for years and know what you’re doing. That being said, offering them something different occasionally can’t hurt. Granted, some specialist species only eat a particular prey item (ex. egg eating snakes) and this doesn’t apply.

I’m hoping you all feed pre-killed, pre-frozen food to your pets. If you feed mice all the time, maybe try to get a frozen chick or quail every so often. Avoid live prey when possible. With live prey you have to worry about parasites, and the possibility of injury to your pet, so please freeze (AFTER humanly killing the prey item).

My advice would be to take a look at your collection. Who is struggling? Do some research on what that particular species eats in the wild. Once you’ve figured that out, look for a food source to fit your snake’s needs. In a perfect world, you will have already done this before getting that shiny, new, captive bred, kick-ass critter. The pet store dude may not know what he’s talking about so find a bonafide breeder. If the breeder is experienced and has bred several generations of the species in question, then they should know the diet details. Stick with what works, but don’t be afraid to fine-tune your snake’s diet. Your snake will appreciate it.

Wines, M. P., Johnson, V. M., Lock, B., Antonio, F., Godwin, J. C., Rush, E. M. and Guyer, C. (2015), Optimal husbandry of hatchling Eastern Indigo Snakes (Drymarchon couperi) during a captive head-start program. Zoo Biol., 34: 230–238.