New study points to Eunotosaurus africanus as first reptile to have anatomy to support a shell.

Scientists trying to determine how the turtle got its shell claim that an extinct reptile from South Africa, Eunotosaurus africanus, is the missing link in the development of how reptiles acquired a shell. There are two theories that offer plausible reasoning as to how the turtle got its shell. One is that the turtle's carapace formed from bony and scale-like growths that developed on the skin of reptiles, while another theory says the shell came to be when the ribs of some reptiles grew broader and straighter.

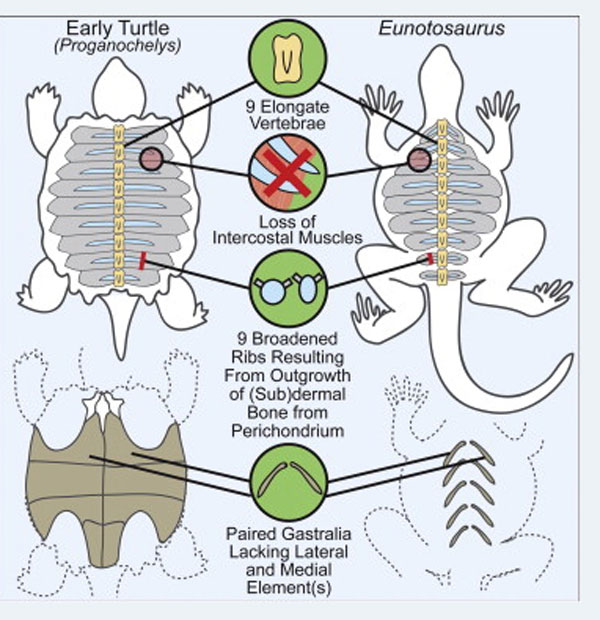

Proganochelys and Eunotosaurus africanus comparison

Studying Eunotosaurus africanus fossils in the field and in museums, scientist Tyler Lyson of Yale University, Gabe Bevers of the Division of Paleontology in the American Museum of Natural History, and Professor Bruce Rubidge of the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa compared its body with that of Odontochelys semitestacea, a 220 million year-old reptile discovered in China that had a fully developed plastron but only a partial carapace.

"The turtle shell is a complex structure whose initial transformations started over 260 million years ago in the Permian period," Tyler Lyson of Yale University and the Smithsonian said in a press release. "Like other complex structures, the shell evolved over millions of years and was gradually modified into its present-day shape."

Want to Learn More?

New Species of Fossilized Turtle Found in Europe

Aquatic Turtle Fossils in Sexual Embrace Discovered in Germany

Eunotosaurus seems to be the transitional reptile that preceded Odontochelys by 40 million years, and modern day turtles in that it had nine broadened ribs that are found only in turtles and do not have intercostal muscles that turtles lack between their ribs. It also lacked the broad spines on its vertebrae that turtles do possess, reorganized respiratory muscles to the ventral side of the ribs, and sub dermal outgrowth of bone.

These discoveries date the beginning development of turtle shells 40 million years earlier than previously thought, to about 260 million years ago. In their paper, published in the journal Current Biology, the researchers detail how the ribs and spine grew thicker on Eunotosaurus before they became fused together to form a shell comprised of 50 pieces. While this will probably refuel the debate as to how the turtle got its shell, Lyson and his colleagues will further study the respiratory system of turtles to determine how their breathing evolved with that of the shell on their backs.