The Dallas World Aquarium has great success breeding the critically endangered Orinoco crocodile.

Crocodilians have always fascinated mankind, and past cultures have worshipped them as gods because of their lifestyle — inhabiting water, land, and caves — as well as venerate them for their strength. The Orinoco crocodile, for one, is worthy of such adulation.

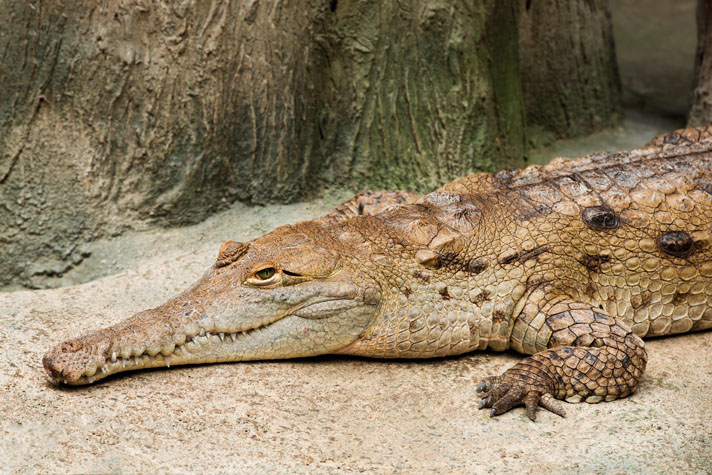

nagel/shutterstock

The Latin species name of intermedius refers to the O-croc’s snout as being an intermediate, between a typical croc snout and a gharial’s.

The Orinoco crocodile was given its Latin name, Crocodylus intermedius, by German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, in describing its narrow snout as intermediate between a crocodile and a gharial. During a Latin American expedition from 1799 until 1804, von Humboldt ventured from the Atlantic into the Orinoco River in Venezuela. There, he observed Orinoco crocodiles, and one was killed and measured to be 21 feet in total length. Based on this encounter, the Orinoco crocodile is considered the largest terrestrial predator on the South American subcontinent, and also longer than the American crocodile (C. acutus) and the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). This suggests this species is one of the larger living crocodilians, just behind the saltwater (C. porosus) and the Nile (C. niloticus) crocodiles.

Having worked for the past 11 years with the Orinoco crocodile (or “O-croc”), including raising hatchlings, I can personally attest to the fact that C. intermedius grows faster than the other two Crocodylus species with which I have had the most experience: the American crocodile and the Morelet’s crocodile (C. moreletii).

The Orinoco crocodile inhabits wetlands associated with the Orinoco River basin, from eastern Colombia across Venezuela. It is locally known as “caiman llanero” (“caiman from the flooded plains”) in Colombia and “caiman del Orinoco” in Venezuela.

The species is considered one of the most endangered crocodilians in the world, and it is listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. It’s status is the result of this crocodile’s reduced distribution, as well as the human pressure on the species due to hunting, net fishing, river pollution, and environmental modifications.

The O-Croc Project at the Dallas World Aquarium

Because the Orinoco crocodile is in danger of extinction in the wild, it became important to maintain the species in captivity. Thus, in the late 1990s, the Dallas World Aquarium (DWA) signed an agreement with the Venezuelan government and Venezuelan NGOs to obtain a pair of Orinoco crocodiles, as well as to support local educational and conservational programs in that country.

The Dallas World Aquarium’s breeding pair of Orinoco crocodiles — Juancho on the left and Miranda on the right.

In 1998, two adult O-crocs from a crocodile farm in Puerto Miranda arrived at the Dallas/Fort Worth airport after a 40-hour trip over land and air. They quickly became ambassadors of DWA conservation projects, and took up residence in the aquarium’s “Orinoco — Secrets of the River” rain forest exhibit that had opened in October 1997.

The female croc, Miranda, was a breeding female in Venezuela, where she produced three clutches of fertile eggs that were hatched successfully at the breeding farm.

Juancho, the male, was a rescued crocodile that spent his first 10 years or so as a pet in a country house. The owners could not care for him as he grew larger, and government officials moved him to the crocodile farm in Puerto Miranda.

Both Miranda and Juancho were so imprinted onto people that they could not be released into the wild. When they arrived at the DWA, they were a little longer than 11 feet, with Miranda being the longer of the two. (She is currently about 12 feet in length and weighs about 400 pounds; Juancho is over 14 feet long and weighs approximately 700 pounds.)

They are kept in a large exhibit measuring about 3,600 square feet with two ponds — a deep one and a shallower one — and the nesting/basking area. The enclosure temperature is maintained at about 72 degrees Fahrenheit. The water is heated to 78 degrees and is filtered 24/7. Water quality is monitored daily, especially because the ponds are also habitat for schools of red-belly piranha and black-fin pacu. A few of the piranha were initially eaten by the O-crocs, and now the school is very alert when they are moving nearby. The pacu, being larger, are not usually chased by the crocs, but they have occasionally displayed scratches on their bodies made by the crocs’ teeth.

Miranda and Juancho are fed once a week, on a diet comprised of large trout with vitamins added. Feedings are usually conducted in front of DWA guests, and we also present a public talk about the species and our conservation program.

The deeper pond is about 5 feet deep (the shallower one is 1½ feet), and this is where mating occurs from September to October. The nesting/basking area measures 10 square feet and is heated around the clock using electric infrared panel heaters. Two 275-watt, Mega-Ray mercury vapor lamps are located six feet above the basking area, and are on for 12 hours a day. The heat from these, coupled with the output from the infrared heat panels, keeps the surface of the sand between 89 and 95 degrees.

No major issues have been observed with our adult O-crocs in 15 years. In fact, we have never had to immobilize them to evaluate or treat them for anything since we received them.

Collecting Crocodile Eggs Can Be Tricky

Breeding activity resulted in a clutch of O-croc eggs in 1999, but because the exhibit lacked a sustainable nesting area at that time, the entire clutch was lost. In 2000, the exhibit was modified to include the basking/nesting area, resulting, in 2003, in the first Orinoco crocodile to be hatched in the U.S.

Another clutch in 2004 produced six crocodiles, and one in 2005 resulted in three. Then, in 2006, with incubation being monitored 24 hours a day and the temperature set for females (sex of hatchlings is temperature-dependent), 36 hatchlings were produced! The learning curve was over, and in 2007, we obtained 20 hatchlings, and in 2008, 30 more.

luis sigler

Fertile Orinoco crocodile eggs during their first week of incubation.

Since then, the crocs’ fertility has been reduced, and even though mating and egg laying continues, the last time we obtained hatchlings was six in 2011.

Around Christmas time (middle December to early January), Miranda will dig her nest in the 20-inch-deep sand bed. It and the shallower pond are located in a part of the exhibit that we can use as a holding area, where we can secure the crocodiles when we enter the primary exhibit to clean, remodel or plant without being threatened by a very temperamental male or a nest-guarding female.

The nest is monitored with a security camera, and soon after Miranda lays her eggs, we extract them to artificially incubate them. She is very protective, though, and sometimes avoids going into the water in order to guard the nest. So patience can be required when we’re trying to retrieve the eggs.

As soon as Miranda allows us to collect them, the eggs are placed in two plastic containers, in an incubation medium comprised of three-quarters vermiculite and one-quarter fine sand. Up to 40 eggs can be incubated at the same time, with each container holding up to four rows of five eggs.

Orinoco Crocodile Egg Incubation and Hatchlings

Orinoco crocodile egg incubation typically lasts about 89 days, give or take a couple. Incubation temperature is set at 87 degrees for the first 40 days; after that, it is increased to 90 degrees. This is a temperature known to produce all females, and because our goal is the conservation of the species, it is preferable to produce as many females as possible, either to release them back into the wild, or to utilize as future captive breeders. Humidity is kept slightly above 92 percent, and the eggs are checked at least three times each day. After day 86, when hatching would be imminent, the eggs would be inspected every morning. Sometimes, two were selected to be X-rayed, in order to determine their development.

luis sigler

A hatchling Orinoco crocodile fully emerged from its egg.

A collective hatching would usually occur over a six-hour period, but sometimes the entire process could take up to two days. The hatchling O-crocs would be left alone to emerge from their eggshells by themselves, but if doing so was taking longer than six hours for an individual, an opening would be created in the shell at the spot the egg pipped. This allows the hatchling to get its head out, breathe, and continue the emerging process.

If a hatchling exhibited an umbilical scar that was very wide, and some of the distended abdomen allowed us to see the yolk sac inside, it would be kept inside the incubator, in a plastic container with a damp paper towel, until the yolk sac was absorbed (a hatchling could spend up to three days in the incubator doing so, with the damp paper towel being changed daily).

Hatchlings with umbilical scars that were nearly closed, and with no distention of the abdomen, were placed in an aquarium with clean, running, filtered water and a dry area beneath a UV light that’s on for 12 hours a day, and a heater that’s on 24/7.

The water depth in a hatchling’s aquarium was enough to allow the baby croc to breathe air at the water’s surface at the same time its rear legs could rest on the bottom of the tank. The clear water and the clear plastic walls of the enclosure would allow us to inspect and evaluate any potential issue with the umbilical scar without having to handle hatchlings.

Hatchling Orinoco crocodiles exhibit a frenzied feeding behavior; just one eating will stimulate the others to do likewise. We would start feeding them on ½-inch, gut-loaded, calcium-dusted crickets every day. Once they were 4 to 6 weeks old, we fed them ¾-inch crickets.

At 12 weeks, live mosquito fish were offered every day. At this age, crocs can also take pink rats, rat pups, and mice once a week, but rodent hair is not digested and may form hairballs. Crocs may cough these up, but feeding them rodents only can cause impaction, especially in youngsters.

The crocodiles would begin to eat live shiners around 6 months of age, and in the case of our animals, these made up the bulk of their diet for the first 12 to 18 months.

Potentially Feisty Juveniles

Juvenile croc husbandry is the same as the hatchlings’, just with larger food items. We also needed to observe the animals carefully to make sure they wouldn’t fight over food. To avoid this, we would have all the crocs’ food ready at once, and throw it as fast as possible to each individual.

Live small fish, such as shiners, stimulate the crocs’ hunting instinct and are a rich food item, making supplementation unnecessary (though it’s mandatory with some thawed fish, such as the previously mentioned trout).

luis sigler

Hatchling Orinoco crocodiles at the Dallas World Aquarium.

Offering higher densities of live fish to the group also helped to avoid dominance issues. In one group of 30 crocodiles that we hatched in 2008, fighting began when fewer animals occupied the same space (as we were moving some into temporary holding areas prior to sending them to other zoological institutions).

When the juveniles were 3 years old, their feeding frequency was reduced to three times a week. At 5 years old, once a week would be enough.

During the initial stages of its Orinoco crocodile project, the Dallas World Aquarium (DWA) committed to the Venezuelan government to send to that country all the O-croc hatchlings originating from the pair of Orinoco crocs Venezuela gave to the DWA.

Thus, in 2007, preparations began for the exportation of 54 live, CITES I-listed, Endangered Species Act-protected Orinoco crocodiles. It would be a daunting task, ultimately taking almost two years to complete, but based on our previous success importing/exporting animals, we were confident it would be done.

It took explaining certain aspects to various government authorities (including why the U.S. was sending Venezuela specimens of that country’s own nearly endemic species; fortunately, friends at the Venezuelan Crocodile Specialist Group helped convince them), but all the required paperwork was finally completed in November 2008.

Want To Learn More?

An Interview With Orinoco Crocodile Expert Dr. Andrés Eloy Seijas

On December 6, 2008, 54 Orinoco crocodiles (30 from 2006, and 24 from 2007) were exported from Dallas, aboard two flights to Caracas. One was nonstop, with 30 crated crocodiles; the other, with the remaining 24 crocs, had a stop in Miami. All the crocodiles arrived in good condition, and after a two-hour drive, they were released into quarantine ponds at Rancho Grande station, in the city of Maracay, Aragua state. Later, after four months in the quarantine facilities, the crocodiles were released in three different protected locations, at the Cojedes, Guaritico and Capanaparo rivers.

It was a great relief to have 54 crocodiles less in our collection, especially if you consider the DWA building is no longer than a city block, even though it holds 800 species and around 8,000 specimens. When we tried to initiate the process for sending the next group of hatchlings, these from March 2008, to Venezuela, the government said they do not need more Orinoco crocodiles from the DWA.

Instead, they authorized us to loan them to different facilities around the world, including the U.S. Today, 29 of those crocodiles are in more than 10 zoos and conservation facilities in the U.S., and six are at the Krokodille Zoo in Denmark. (We kept one of the crocs hatched in 2008 as a future replacement for our own display.)

The next step for the DWA, as we strive to continue our Orinoco crocodile conservation efforts outside of Venezuela and Colombia, is to import a group of subadult males in order to pair them with some of the females in the U.S.

luis sigler

Crocodile biologist Ricardo Babarro releases an Orinoco crocodile at Capanaparo River.

The situation in the wild is critical, and although having a genetically healthy population of Orinoco crocodiles in captivity may be beneficial to the species survival in the long run, the most important conservation efforts still need to be done in the Orinoco River basin in Colombia and Venezuela.

On June 20, 2016, the Gladys Porter Zoo, in Brownsville, Texas, hatched its first Orinoco croc, making it the second zoo to breed the species outside its natural range. Its O-crocs were hatchlings from Venezuela that were raised in Canada. They were transferred to the zoo in 2011, and five years later they bred successfully.

Ricardo Babarro

The author releases a 2-year-old Orinoco croc at a quarantine station in Venezuela.

Let’s hope the future brings additional breeding successes at other institutions, helping toward the ultimate goal of ensuring that the critically endangered Orinoco crocodile survives for many years to come.

The author dedicates this article to Federico Medem, Tomas Blohm and John Thorbjarnarson for their Orinoco crocodile conservation efforts in Colombia and Venezuela, and to Daryl Richardson for his commitment to preserve the species from the U.S.

Luis Sigler is a veterinarian who has been working with crocodilians for 28 years. He worked in Mexico as a crocodile researcher and zoo curator for the Miguel Alvarez del Toro Zoo in Chiapas, and since 2005, he is at the Dallas World Aquarium serving as reptile curator and conservation biologist. He is the Orinoco crocodile studbook keeper for the Crocodile Advisory Group of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, and a member of the Crocodile Specialist Group of the IUCN since 1992.