Information on how natural and artificial lighting affects reptiles.

To reptiles, sunlight is life. Reptiles are quite literally solar powered; every aspect of their lives is governed by their daily experience of solar light and heat, or the artificial equivalent when they are housed indoors. Careful provision of lighting is essential for a healthy reptile in captivity.

Infrared and Visible Light Effects on Reptiles

The spectrum of sunlight includes infrared, “visible light” (the colors we see in the rainbow) and ultraviolet light, which is subdivided into UVA, UVB and UVC. Very short wavelength light from the sun (UVC and short wavelength UVB) is hazardous to animal skin and eyes, and the atmosphere blocks it. Natural sunlight extends from about 290 to 295 nanometers, which is in the UVB range, to more than 5,000 nanometers, which is in the long-wavelength infrared (heat) range.

Infrared light is the sun’s warmth, and basking reptiles absorb infrared radiation extremely effectively through their skin. This part of the light spectrum is invisible to humans and most reptiles, but some snakes can perceive the longer wavelengths (above 5,000 nanometers) through their facial pit organs. Ceramic heaters and heat mats emit only infrared. Incandescent lamps emit infrared and visible light. Some incandescent red basking lamps are described as “infra-red” lamps, but these also emit red visible light.

Visible light, including UVA, is essential. Many reptiles have extremely good color vision. Humans have three types of retinal cone cells for color vision, and their brains combine the information from these cells and perceive the blend as a certain color. Most reptiles, however, have a fourth cone type, which responds to UVA. These reptiles see a much more colorful rainbow than humans do, which makes providing natural lighting quite a challenge. This extra color perception is especially important to many reptile species in recognizing others of their species and even food items.

Some nocturnal geckos lack the red-sensitive cone, but their green-sensitive cone also responds to red light; they can certainly see it. Studies have even shown that some use their cone types for color vision in light similar to dim moonlight. Thus it is possible that “moonlight blue” or “red night light” lamps, which usually are much brighter than moonlight, alter these animals’ view of the twilight world.

Sunlight also has effects unrelated to conscious vision. A reptile’s eyes, and the parietal eye (third eye) in those species that have one, transmit information to other parts of its brain responsible for setting circadian (daily) and circannual (yearly) rhythms. There are even light-sensitive areas of the reptilian brain that respond directly to sunlight’s glow through the skull. The length of day and night, the sun’s position in the sky, and the intensity and amount of blue in sunlight all give precise information about the time of day and season of the year. In response, a reptile adjusts its activity levels, and daily and seasonal behaviors, such as its reproductive cycle and thermoregulation needs. Even nocturnal species govern their behavior by monitoring day and night from their daytime hiding places.

No artificial lighting system in the world can provide the full spectrum and intensity of natural sunlight, its subtle changes in color as a day progresses, or the sun’s movement across the sky. For these reasons alone, the more natural daylight a reptile experiences, the better. “Natural daylight” may not always mean full sunlight; a herpkeeper must aim to provide species-appropriate lighting.

See the Reptile Light Difference

Humans have three cone types for color vision. A blue-sensitive cone enables us to see from about 400 nanometers (purple), and our green- and red-sensitive cones respond to light up to nearly 700 nanometers (red).

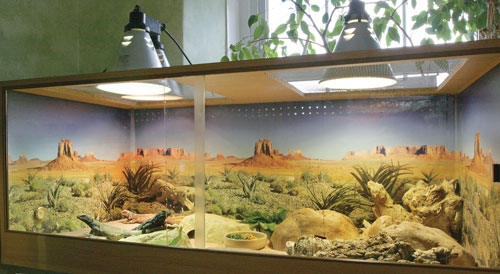

Photo by Frances M. Baines

This melamine glass-fronted vivarium measuring 4 feet long by 2 feet wide by 2 feet tall shows appropriate lighting for chuckwallas (Sauromalus ater). The main basking area combines light from an 80-watt household PAR38 tungsten flood and a 100-watt Reptile UV MegaRay SB Mercury Vapor Lamp. Another household flood lamp lights the secondary basking site. Four artificial caves provide shelter in different temperature zones

Most diurnal lizards, however, have a fourth cone type that responds to UVA. For example, the eyes of a red-eared slider (Trachemys [Pseudemys] scripta elegans) perceive all the colors humans recognize as well as higher-wavelength UVA (from 350 nanometers) and low-wavelength infrared (up to about 750 nanometers). This extra perception almost certainly adds additional colors to the turtle’s rainbow. Some nocturnal geckos, such as Hemidactylus turcicus, lack the red-sensitive cone. Although they may not be able to distinguish red from green, they can certainly see it just like colorblind humans can. Geckos have superb color vision in other parts of the spectrum. For example, they can distinguish blues from browns in extremely dim light where humans see no color at all. See figure 4.

Reptile UVB Light

Ever wondered why basking lizards flatten to increase their surface area, or why tortoises and turtles bask with their neck and legs extended, or why shade dwellers and crepuscular species usually have thinner, more translucent skin that allows deeper penetration of diffused and reflected light? It’s because sunlight has direct effects upon reptiles’ exposed skin.

Photo by Frances M. Baines

A reptile uses information such as light’s intensity and color, and the length of day and night to adjust behavior to changing seasons.

UVB in sunlight has a direct effect upon the immune system in skin and may also stimulate production of beta endorphins, giving sunlight its feel-good factor. But this range of the light spectrum is best known for its role in skin synthesis of vitamin D3. For this to occur, sunlight must contain UVB in wavelengths ranging from 290 nanometers to about 315 nanometers. Most glass and plastics block these wavelengths, and the atmosphere also partially blocks them, so the sun must be fairly high in the sky for significant amounts of UVB to be found in sunlight. However, even at higher latitudes, including northern U.S. states and most of Europe, there is sufficient UVB for vitamin D3 synthesis from midmorning to midafternoon in sunshine from April to September and from early morning until late afternoon in midsummer (mid-May until late July).

Photo by Frances M. Baines

As this diagram shows, the full solar spectrum of light is important for reptile health.

Vitamin D3 synthesis in reptiles requires warmth as well as ultraviolet light. UVB converts a cholesterol in the skin to pre-D3, and this is converted into vitamin D3 very rapidly when a reptile is at its optimum temperature. The vitamin is toxic in large amounts, which is one reason giving it as a supplement can be risky (always follow manufacturer instructions regarding supplementation), but reptiles never generate too much D3 in their skin while basking. Natural levels of higher wavelength UVB and UVA prevent overproduction. They convert excess pre-D3 and vitamin D3 into harmless byproducts as soon as they start building up.

Several manufacturers make UVB-emitting bulbs for reptiles. Measuring a reptile lamp’s UV intensity at different distances is one way to assess the lamp’s value in terms of its ability to help in vitamin D3 synthesis and its safety (excess radiation can be harmful to a reptile’s skin and eyes). This UV intensity can be categorized using the UV Index, the same scale weather forecasters use, and accurate meters designed for lamp measurement must be used (the sensors of inexpensive UV Index meters designed to measure sunlight don’t register harmful nonterrestrial, short wavelength UVB). Herpkeepers can find UV Index recordings for a wide range of lamps on the UV Guide U.K. website: uvguide.co.uk.

Photo by Frances M. Baines

A UV-transmitting skylight helps light the Komodo dragon enclosure at ZSL London Zoo in the U.K.

The maximum UV Index appropriate for each species must be determined using knowledge of the microhabitat of the reptile in the wild. Reptiles that stay in shade, or only bask in early-morning or late-evening sunlight require far lower values than species that bask in late-morning tropical sun.

Photo by Frances M. Baines

Lamp Position – All light sources should be above a reptile’s head — not to the side

Reptile Outdoor and Indoor Lighting

In every ecological niche, different species have evolved behaviors and bodily characteristics enabling them to use full-spectrum light from the sun in the most efficient way. Many reptiles benefit from outdoor enclosures whenever ambient temperatures are suitable. Whether or not they require direct sunlight depends upon the species, but all species require access to full shade and shelter.

Sometimes aspects of outdoor lighting can be brought indoors. Room-sized enclosures can be equipped with skylights and windows glazed with special UV-transmitting acrylic or glass. Trade names for such UV-transmitting products include Perspex, Plexiglas and Lucite (acrylics), and Starphire (low-iron glass), all of which must be special ordered. Even then, supplementary UVB may be required. Heat built up by direct sunlight through glass must never be ignored, either.

Photo by Frances M. Baines

Does this look safe to you? The temperature of the substrate under this basking lamp might be perfect, but the tortoise’s carapace is nearly 10 inches closer than this to the lamp. Take into account your reptile’s height when checking temperatures.

Unfortunately, comparatively few reptiles in captivity experience truly natural lighting. Most are housed indoors and behind glass, and they rely upon artificial light to make their day. Adequate light in captivity is best provided by emulating the reptile’s natural environment, including a temperature gradient as found in the species’ microhabitat. These provisions allow the reptile to decide how much heat, visible light and UV radiation it experiences each day.

Artificial Sunlight Options for Reptiles

Most lizards and chelonians, and many snakes, need high levels of full-spectrum lighting, which must include UVB and UVA. Herpkeepers must aim to to use the lamps available to provide pets with their specific lighting needs.

Incandescent (tungsten or halogen) lamps provide excellent heat and visible light for a basking spot, and they can be thermostatically controlled. Standard type-A household bulbs or flood lamps with a beam at least 30 degrees wide work fine. Their predominantly red-and-yellow light is deficient in blue light and UVA, and they do not emit UVB. These complement all UVB-emitting reptile lamps, which have little red or yellow light, extremely well. Incandescent lamps connected to timers can produce a simple effect for dawn and dusk. Timers can switch them on just before, and off just after, the UVB lamps.

Photo by Frances M. Baines

Incandescents (A), “daylight” fluorescents (B), UVB fluorescent tubes (C), mercury vapor lamps (D) and UVB metal halide lamps (E) are among the bulbs used in reptile husbandry.

“Daylight” fluorescent tubes are sometimes called “full-spectrum” lights, but they do not produce sufficient UVB for vitamin D3 synthesis in reptiles. Some brands produce traces of UVB and a little UVA. They can be useful for improving general light levels in cooler areas of a vivarium.

UVB fluorescent tubes produce diffuse, low levels of UVB resembling outdoor shade on a sunny day. They emit less visible light than other bulb types. These tubes are suitable for supplying UVB to species that do not bask in sunlight, such as some forest shade-dwellers, or for small enclosures where the heat from mercury vapor lamps would cause problems with the thermal gradient. Always combine them with a better visible-light source. Quality tubes emit light with a UV Index between about 0.5 and 1.0 (sunlight in the tropics before 7:30 a.m.) at 12 inches (the usual maximum distance suggested), and they need to be replaced every year.

UVB compact fluorescent lamps also produce diffuse, low levels of UVB at basking distances. However, at close range and/or if reflectors are used, the light and UVB may be intense, making good positioning difficult. These lamps decay more rapidly than tubes and may need replacement after six months.

A few brands of fluorescent lamps for reptiles, both compact and tube types, have been found to emit hazardous shortwave UVB. These have caused eye problems such as photokeratoconjunctivitis. Some manufacturers that experienced the problem say they have addressed the issue, while others are still addressing it. However, if your reptile develops swollen eyes or refuses to open them shortly after a new lamp is installed, see your herp veterinarian immediately. You may wish to refer him or her to this article. Lamp placement, the lamp itself and/or other factors could be responsible.

Mercury vapor lamps vary in quality and UVB output. These lamps also produce significant heat, and they cannot be thermostatically controlled, so they are most suitable for large enclosures. Be sure to follow the manufacturer’s guidelines and instructions for proper lamp placement and distances. Several mercury-vapor-lamp types are available. Inexpensive spot lamps with clear-glass faces may produce extremely narrow, hazardous beams of intense UV light and are best avoided. Flood lamps have much wider beams, and they are ideal for reptiles that naturally bask in the sun. They create directly below the lamp a zone of bright light and UVB resembling a small patch of sunlight. Brands vary in their UV Index. Recordings range from about 2.0 (full tropical sun before 8:30 a.m.) to 7.0 (full tropical sun between 9 a.m. and 10 a.m.) within the basking area.

Metal halide lamps are rapidly gaining a place in, or rather over, the vivarium. Like mercury vapor lamps, metal halides are most suitable for large enclosures and cannot be used with a thermostat. Most do not produce UVB. “Daylight” versions with a color temperature between 5,500 and 6,500 Kelvin are the best choice for creating the look of sunlight. Used with care, these lamps are superb for simulating bright daylight in a large vivarium when combined with a UVB lamp. However, they require an external ballast, and positioning them is crucial. At close range the visible light is extremely intense, and the lamp must never be looked into directly. Manufacturers are developing UVB-emitting metal halides designed specifically for reptiles, and early test results look promising. Although the UV Index range can vary depending upon the brand, some sample lamps I tested for UV Guide U.K. were emitting light with a UV Index between 2.5 and 5.0 (full tropical sun between 8:30 a.m. and 9:30 a.m.) at 18 inches.

To reptiles, sunlight is life. Artificial sunshine is not ideal, but there are now many combinations of lamps, bulbs and tubes available. When used with care and sensitivity, they will go a long way toward meeting the needs of all reptiles in captivity.

Reptile Lighting Advice

- Trust your reptile to know what it needs. Reptiles are extremely competent at deciding how much heat, visible light and ultraviolet radiation they need at any given time. Captive reptiles need a sufficiently large, species-appropriate microhabitat with suitable heat, light and UVB gradients, shelters, and basking areas, so they can select their preferences like they would in the wild.

- UVB, UVA, visible light and heat go together. Because vitamin D3 synthesis in reptiles occurs only in warm skin exposed to UVB, ideally a UVB lamp needs to be over the basking area. Pairing the UVB source with the basking lamp is always a winning combination.

- Like the sun, lamps should be overhead. Reptiles have eyebrow ridges, and some have upper eyelids, for a reason: They shade the surface of the eye. All light sources should always be directly above a reptile’s head, not to the side. Lights shining sideways into its eyes are stressful (think of driving a car toward the setting sun). Also, intense visible light, as well as UVA and UVB, can seriously damage eyes.

- Keep a respectful distance. In the author’s opinion, no lamp or tube should be closer than six inches from the reptile, even when positioned directly overhead. Heat lamps usually require much greater distances than this. At close range many lamps are frankly dangerous. Most quality UVB lamps have minimum and maximum recommended distances, and these must be carefully observed.

- No spots please! Basking spots should be basking zones. A reptile’s whole body must fit within the high-temperature, brightly lit basking area. Flood lamps are essential. Narrow spot lamps may only heat a small patch of skin, which may become dangerously hot while the rest of the body remains cold. The hapless creature may stay where it is, trying to warm further, and sustain thermal burns.

- Always double-check your temperatures. It is vital to check the temperatures reached under a lamp. Take into account the height of a lizard’s head and shoulders, or a chelonian’s carapace, when doing this.

- Allow reptiles to set their patterns. Reptiles rely upon a distinct day and night to set their circadian rhythms. Day must be light; night must be dark. Use timers to provide the correct photoperiod for the species. If nighttime heat is required, ceramic heaters or heat mats mounted on a rear wall are more suitable than night lamps.

I would like to thank Janette Beveridge, John Binns, Gary Ferguson, William Gehrmann and A.J. Gutman for their most helpful comments and suggestions.

| FRANCES M. BAINES, M.A., VetMB, MRCVS, is a veterinarian researching the requirements of reptiles for visible and ultraviolet light. She writes on uvguide.co.uk and, with colleague Andrew Beveridge, independently assesses reptile lamps worldwide. She is currently an advisor to the Reptile and Amphibian Working Group of the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums. |