UVB lighting is a necessity, not an accessory! Here’s why.

When choosing the best lighting options for your pet reptiles and amphibians, it can get confusing. There are so many different wattages, bulb types, and functionalities, not to mention lighting rigs and hardware. But when it comes to UVB light in particular, you might wonder why you need it if your lizard is happy with a strong basking bulb.

An In-Depth Look At UV Light And Its Proper Use With Reptiles

Captive reptiles need both basking and UVB light. Basking bulbs do not provide UVB. This naturally comes from the sun, which is why pet reptiles love sunny rooms and getting to explore outside. Unfortunately, UVB can’t pass through glass. You and your iguana might feel warmth on a sunny windowsill, but they won’t get their much-needed UVB this way. When pet reptiles live indoors, they need a steady source of both UVA and UVB light.

Green anoles are considered partial sun seekers, occasional baskers. They are a Zone 2 reptile. Photo by Ami Atari/Shutterstock

UVB light isn’t visible to reptiles, but it enables the synthesis of a vital nutrient, vitamin D3, in the skin. UVB and warmth, together, transform a natural cholesterol into this vitamin, which is used by every organ in the body for different functions. The most important one is enabling the gut to take up calcium from the food – calcium is vital for healthy bones and for all muscles and nerves to function properly. Vitamin D also supports the immune system, the kidneys, the digestive system, the brain, growth, and reproduction. Reptile multivitamins containing D3 can help, but they are not a substitute for species-appropriate UVB lighting.

Sonoran mountain kingsnake. It is a Zone 2 reptile. Photo by Matt Jepson/Shutterstock

Metabolic Bone Disease (MBD) is the most common disease of reptiles deriving from nutritional and housing failure. Without suitable UVB lighting, appropriate heating, and a balanced diet, pet reptiles can become malnourished and develop debilitating illnesses that cut their lives short. MBD is one such condition, most often the result of vitamin D3 deficiency causing inadequate uptake of calcium from the diet. This is easily prevented by ensuring your reptile has the right UVB lighting and heating for the species and an adequate supply of calcium in the diet.

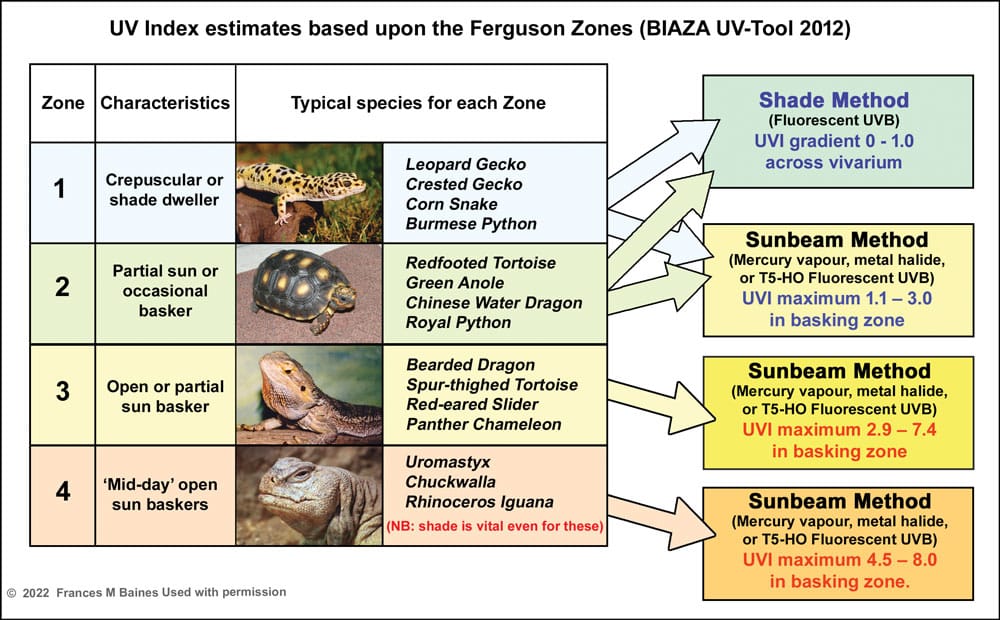

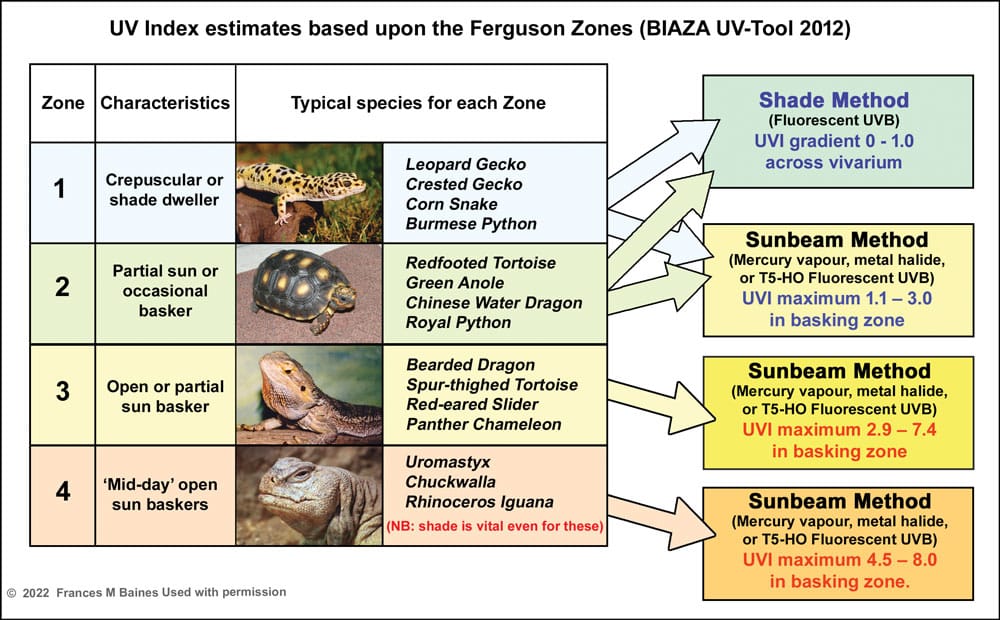

Ferguson Zones revised 2022. Frances M. Baines used with permission.

Reptiles can see UVA light, and they need it just like UVB. UVA is a “color” to them. This UVA-color is often in their skin patterns and markings, helping them recognize each other as male and female; many foods also reflect UVA color, so it may help stimulate a feeding response and other behaviors. Like UVB light, UVA is part of sunlight but is also emitted by all UVB lamps sold for reptiles. It’s also present in small amounts in ordinary incandescent lamps, like halogens, used as basking lamps, but none is emitted by “white” LEDs even if they are labeled “full spectrum.”

If you want your scaly companion to have a long, happy, and healthy life with you, UVB lighting cannot be neglected.

How UVB is Different from Basking Lights

Basking bulbs are halogen bulbs or other incandescent lamps such as older-style reflector bulbs, and they emit heat (visible light and short-wavelength infrared, as in sunlight) based on their wattage, width of beam, and proximity to the basking area. Adjustable clamp lamps and stands can direct where the light goes when the bulb is in a dome reflector, but some enclosures have built-in sockets or fixtures that just project the light downwards.

The black and white tegu (Tupinambis merianae) is a Zone 3 reptile, a partial or open sun basker. Photo by BSG_1974/Shuttestock

Because the resultant basking temperature and gradient vary based on the enclosure’s size and overall setup, a spot-check thermometer or “temperature gun” can help you determine if your basking bulb needs more or less wattage, or a wider beam, to adjust the temperature. The basking zone must always be at least as large as the whole body of the reptile when basking under it. Basking lamps can be controlled by a dimming thermostat.

The desert iguana (Dipsosaurus dorsalis) is a Zone 3 reptile, a partial or open sun basker. Photo by Milan Zygmunt/Shutterstock

The ambient (air) temperature can also be boosted by ceramic heat emitters (CHE), especially if the light fixture is far from the floor in a tall enclosure. However, CHE are not basking lamps. They only emit long-wavelength infrared – the same type of heat as BBQ coals, very different from sunlight.

UVB fluorescent lamps serve a totally different purpose. They don’t emit heat and can’t be put on a dimmer or thermostat. They are graded according to their intensity.

All UVB lighting emits both UVB and UVA. This is because the phosphors used in fluorescent lamps emit all wavelengths from UVB through UVA to visible light; and the mercury in mercury vapor lamps emits “spikes” of radiation in the UVB and UVA ranges. There are two basic types: compact lamps – either bar-shaped or coiled – which are shaped like household “energy-saving” bulbs and screw into regular lamp holders; and fluorescent tubes, either T8 (1” diameter) with low UVB output or the newer T5-HO tubes with high UVB output; fluorescent tubes fit in specially-designed fixtures with reflectors above them.

UVB mercury vapor bulbs are another type of lamp that has a screw fitting like regular bulbs but can emit both heat and UVB, and all emit UVA as well. However, you need to research whether they are safe to use with your reptile. The heat or UVB may be too intense for them. Using different bulbs for heat and for UV can make it easier to customize to their needs, although desert lizards and other daytime baskers like Kimberley rock monitors tend to do well with all-in-one mercury vapor bulbs in large open-topped enclosures.

Creating a “Patch of Sunlight”

Reptiles, being ectotherms (“cold-blooded”), need to warm up their bodies every day using external heat sources, and they need to be able to adjust their exposure to heat constantly to keep their body temperature optimal for activity and life. They do this by moving in a temperature gradient, sometimes seeking to gain heat, sometimes retreating to cooler areas to lose heat – this is “thermoregulation.” It is often provided, in captivity, by creating a “patch of sunlight” – a basking zone with higher heat, light, and UV, and a cool zone further away, with a gradient from warm to cool, bright to shaded, high UV to low UV, in between.

Whatever type of UVB lamp is used, its beam needs to blend with the beam from the basking lamp to create the “sunlight,” and so these lamps need positioning together. This basking zone must be big enough to warm and light the whole body of the occupant. “Spot” basking lamps are rarely appropriate; look for types with wide flood beams. Compact UVB fluorescent lamps only provide UVB over small areas, which is mainly useful in small terrariums for small reptiles. Fluorescent tubes have far better coverage; T8 (1” thick) tubes provide low-level UVB; T5-HO slim tubes in reflector fixtures can provide sun-strength UVB over wide areas.

LED UVB Lighting

Modern technology may, in the near future, bring us LED lights that emit a full spectrum of light with plenty of UVB and UVA while saving on energy bills. Select legacy herpetoculture brands have been experimenting with UVB-emitting LED lamps for reptiles already, but as yet, there are still significant questions about their long-term safety. Their spectra are very different from sunlight, and in theory, they could produce excessive amounts of vitamin D3 in reptile skin, leading to toxicity.

The crested gecko may only need minimal UVB as it is more active at night. It is a Zone 1 reptile. Photo by Christian Rogers Photography/Shutterstock

Enterprising makers in the hobby are also building LED solutions in both bulb and hood formats, but as yet, none have been tested for their safety in long-term use. Some Chinese brands have already been found to emit harmful levels of UVB and even UVC; some have been withdrawn from sale. On the other hand, “white light” LEDs which do not emit any UVA or UVB are an excellent choice for boosting visible light in a vivarium. While they carry a higher price tag than traditional bulbs, LED can be worth the investment for its sustainability factors. LED units last a few years, don’t require frequent bulb purchases, and the diodes are made of durable materials. LED lighting doesn’t produce heat, but heat-emitting models fitted with infrared diodes could hit shelves and reptile expos in the near future with further innovation.

UVB Ranges: The UV Index (UVI), Ferguson Zones, and the %UVB Number on the Box

You need to consult a care sheet for your reptile to find out how much UVB it requires. Generally, so-called “desert” animals, like bearded dragons, which live in open country with plenty of sunlight, require high levels of UVB. On the other hand, forest-dwelling and nocturnally-active reptiles, like crested geckos (often called “tropical” or “rainforest” species) may only need minimal UVB.

The Reeves turtle is a Zone 3 reptile. Photo by Luciano de la Rosa/Shutterstock

But you might be perplexed when you research care sheets and UV charts. What do these multiple numbers mean? How come they don’t align with the number on the box, such as 6%, 12%, or 5.0 and 10.0, when you’re shopping for UVB bulbs?

Are you familiar with the UV Index (UVI) that appears in weather forecasts? We are often told to wear sunscreen if the UVI exceeds 3.0 (equivalent to morning sunlight in summer). The UV Index is also a reasonable indication of the ability of the UVB from the sun – or a lamp – to synthesize vitamin D in the skin. Different reptiles living in different microhabitats expose themselves to ranges of UVI over the course of a day. So a sun-loving “desert” lizard might bask in sunlight at UVI 4.0 – 4.5 and then move to shade with zero UVI; a shade-dwelling snake might only bask briefly at UVI 1.0 and then move to shade with zero UVI.

Ferguson Zones revised 2022. Frances M. Baines used with permission.

Ferguson Zones, a recent invention named after herpetologist Dr. Gary Ferguson who devised them in 2010, simplify these micro ranges into four different Zones. The Zone ranges are based on Dr. Ferguson’s studies and observations of thermoregulatory behaviors in reptiles and how they interacted with sunlight while navigating their environments. The Ferguson Zone concept is that reptiles typical of each Zone should be offered UV in the basking zone – their “sun patch” – up to the maximum in that Zone range and then a gradient to zero in full shade in the cooler parts of the vivarium.

What About the Number on the Box?

Chances are that you’ve seen UVB bulbs labeled with 5.0 or 10.0 at most chain pet stores. Compact and full-size UVB bulbs both have these grades. You’ll find grades in the middle, usually 6.5 or 7.5, at reptile expos and independent reptile shops. These numbers might sound alarming after reading the chart above.

Red-footed tortoise. It is a Zone 2 reptile. Photo by cooky_luvs/Shutterstock

The number on the box refers to how much of the bulb’s output is UVB. If it says 5.0, or 5%, then 5% of the bulb’s total output is UVB while the rest is dedicated to UVA and visible light. A 10.0 or 10% label means that 10% of the output is UVB, and so on. The manufacturer will usually include a chart on the box or their website explaining each of their products’ Ferguson Zone and UVI equivalents as well. The higher the percentage of UVB, the “stronger” the lamp; what that means in practice is that a “stronger” lamp will produce your desired UVI level at a greater distance away from it than a “weaker” lamp from that same product range.

The ball python is a partial sun occasional basker. It is a Zone 2 reptile. Photohobbiest/Shutterstock

When buying UVB bulbs, look at the size of the bulb and the labeling (e.g. Ferguson Zone rating, UVI, or %UVB) rather than the wattage.

Wattage is a more important measure for basking bulbs. Fluorescent UVB bulbs vary widely from little T5 8-watt models to 54-watt 44” T5-HO 10.0 tubes and all ranges between. Mercury vapor bulbs are available up to 160 watts. The %UVB is also only useful up to a point; ignore terms like “desert” or “tropical.” What is more important is how close your reptile will get to the lamp. Lamps with higher %UVB will likely give you the desired UVI at a greater distance but possibly be unsafe with very high levels at close range.

When you see charts with UVI and Ferguson ratings, take into account how close your pet gets to the UVB light source. You’ll see that the closer it gets to the lamp, the higher the UVI, as well as the heat and visible light. The manufacturer should have a chart for each lamp in their product line-up, detailing the ranges available at different distances, so you can decide which product will give a suitable UVI over your animal when it’s basking under the lamp at your chosen distance.

Panther chameleons are Zone 3 reptiles, a partial or open sun basker. Photo by Jan Bures/Shutterstock

For example, suppose you want your bearded dragon to have UVI 4.5, and he will be 10-12 inches below the lamp. A “desert” 12%UVB Arcadia T5-HO 22” Kit will be too strong – the correct distance for UVI 4.5 would be 16 inches. But the “forest” 6%UVB version is ideal, with UVI 4.6 at 10 inches distance.

Then if you have a UV index meter, you can simply use this to measure the UVI and position the lamp accurately when you set up your vivarium. You also need to bear in mind that if your lamps are placed above a mesh screen top, the mesh blocks some of the light and UV from getting through. Different manufacturers make mesh with different-sized holes. For example, ExoTerra mesh screen lets through 65% of the UV, whereas Custom Reptile Habitats vivarium mesh lets through 77%. You can calculate the UVI at any distance below a screen using that knowledge and the manufacturer’s chart if you don’t have a UV index meter. Or you can use conversion charts; for example, the Facebook group Reptile Lighting has charts for T5-HO UVB tubes placed over a wide range of mesh brands.

Why You Need to Change UVB Bulbs Every Six to Twelve Months

Basking bulbs need to be replaced once they burn out. The average incandescent lamp lasts 1,000 to 2,000 hours. That’s 3-6 months’ use at 10-12 hours per day. UVB bulbs need to be changed every six to twelve months, even if the bulb hasn’t burnt out unless you have a UV index meter and can see that the UVI reading is still within the desired range.

The blue-tongued skink is a Zone 3 reptile. Photo by christopher pb/Shutterstock

Ths is because the special glass that a UVB tube or bulb is made of slowly becomes less transparent to UV with use, but the visible light is not noticeably lessened at all. This is called “solarisation.” Cheap brands use glass that solarises faster than that used by some of the top brands.

Choose High Quality UVB Lights

In general, high-quality German-made tubes from Zoo Med and Arcadia solarise very slowly and typically keep a high output for at least a full year of use. Some cheaper lamps solarise much faster, and a six-month replacement is often needed. Compact lamps, which get much hotter owing to the close proximity of each coil, also often need replacing after six months of use. Because UVB bulbs have such low wattage and other internal components, it can seem deceptive to throw out a seemingly operational bulb after six months.

Don’t fall for the glowing trickery: set reminders to change the bulb every six or twelve months according to the manufacturer’s recommendations or use a UV index meter. Do not rely on one of the color-changing UVB “detector cards” under the bulb to test if it’s still emitting UVB. The dye responds to UVA rather than UVB, so you can get completely false readings with these.

References and Further Reading

Ferguson, G. W., Brinker, A. M., Gehrmann, W. H., Bucklin, S. E., Baines, F. M., & Mackin, S. J. (2010). Voluntary exposure of some western‐hemisphere snake and lizard species to ultraviolet‐B radiation in the field: how much ultraviolet‐B should a lizard or snake receive in captivity?. Zoo biology, 29(3), 317-334.

Wacker, M. and Holick, M.F., 2013. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermato-endocrinology, 5(1), pp.51-108.

Baines, F., Chattell, J., Dale, J., Garrick, D., Gill, I., Goetz, M., Skelton, T. and Swatman, M. (2016) How much UV-B does my reptile need? The UV-Tool, a guide to the selection of UV lighting for reptiles and amphibians in captivity. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 4(1): 42 – 63

Baines, F. M. (2018) Lighting. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. 1st Edn. Eds Doneley, B., Monks, D., Johnson, R. and Carmel, B. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp 75 – 90

Wunderlich, S., Griffiths, T., & Baines, F. (2023). UVB-emitting LEDs for reptile lighting: Identifying the risks of nonsolar UV spectra. Zoo Biology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21806