Dehydration is a common and serious problem in herps, and I am frequently asked about or presented with herps that are in need of fluid supplementatio

Dehydration is a common and serious problem in herps, and I am frequently asked about or presented with herps that are in need of fluid supplementation. The classic situation occurs when an owner does not notice that an animal’s water dish is empty and neglects to refill it. Many herps are kept in cages with heat lamps that may cause the water to rapidly evaporate; in other situations, the animal may knock the water bowl over.

Read More

How to Recognize and Prevent Medical Ailments in Amphibians

Three Common Ailments Of Tortoises In Captivity

Douglas Mader

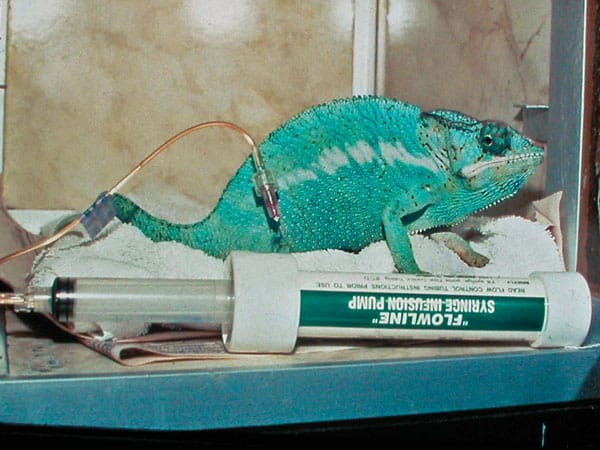

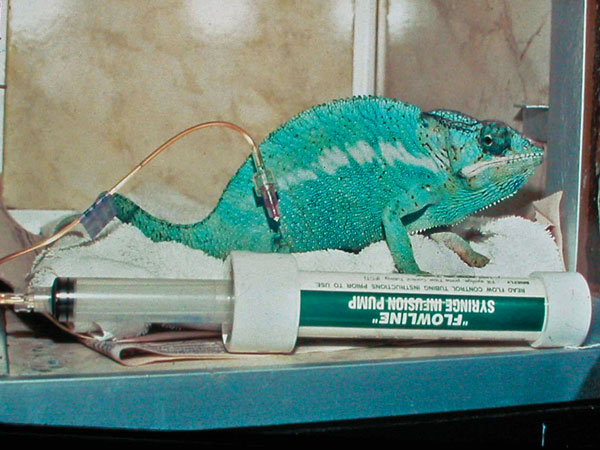

This panther chameleon is receiving intraosseous fluids via a syringe pump.

Dehydration can also occur in animals that are given water, but that are kept too hot or in an environment that is too dry. Consider a green iguana that is housed indoors, with a heat lamp, in an air-conditioned house. The lamp, while keeping the iguana’s cage warm, dries the moisture out of the air, which can induce a state of chronic dehydration in the iguana.

The most important thing to remember when administering fluids to ill reptiles is that if the mouth works, use it. All too often, veterinarians rush to administer fluids subcutaneously, intracoelomically or via the intraosseous route. In many situations, oral fluids are just as effective, and in some cases, more so. This is the thinking behind soaking a reptile when it needs fluids—doing so simply gives the animal a chance to drink.

If you don’t see the animal drinking while soaking, however, don’t assume it will be rehydrated just because it is soaking. There is an old wives’ tale that a herp will suck fluid up through its cloaca. While it is true that some turtle species do experience electrolyte exchange across their cloacal membranes, and some turtles do reabsorb urinary fluids in their bladders, I have seen no proof that herps in general are able to absorb enough water through their cloacas to replace fluid deficits.

I once had a student conduct a study using six red-footed tortoises. They were weighed, and blood was drawn from the tortoises to check for packed cell volume (PCV) and total solids (TS). The tortoises were then soaked for 30 minutes in fresh water.

After the soaking, the same tests were repeated. If an animal is dehydrated and then given fluids, its weight should increase and both the PCV and the TS should decrease. When the before and after soaking numbers were compared, it was found that all the tortoises lost weight and the PCV/TS values did not change. It turned out that when the tortoises were placed in the water to soak, they urinated—hence, the weight loss. This is significant, because in this case the weight loss equaled fluid loss—exactly the opposite of what is needed in a dehydrated animal.

Regardless of how fluids are administered, all reptile patients must be maintained at their preferred optimum temperature in order to process and efficiently utilize supplemental fluids.

The principles of fluid therapy are universal across species lines. A basic understanding of body water distribution, forces governing water movement between fluid compartments, fluid pharmacology and patient assessment are necessary to determine the fluid type, dose and rate of fluid to be administered to a dehydrated reptile. The physiologic properties of water in reptiles is comparable to that of other vertebrates.

There are three basic types of fluids that are used to rehydrate reptiles: isotonic (does not promote fluid exchange), hypotonic (increases erthrocyte [red blood cell] volume) and hypertonic (decreases erthrocyte volume). A fourth fluid, which is actually a combination of several different fluids, used in herp patients is called Reptile Ringer’s. This is a hypotonic fluid and was popular many years ago, but it has fallen out of vogue as more has been learned about fluid and electrolyte balance in reptiles.

The three most common types of fluids used in veterinary medicine are Lactated Ringer’s Solution (LRS), Normosol-R and Plasmalyte. These are all considered isotonic.

These fluids have the capacity to act as physiological buffers. They are metabolized in various organs of the body to bicarbonate, and bicarbonate acts as a buffer to counteract acidosis seen in dehydration.

Lactated Ringer’s Solution uses lactate as the buffer. Lactate is transformed into bicarbonate via the liver.

Normosol-R uses acetate as the buffer. Acetate is tranformed into bicarbonate via muscle.

Plasmalyte use gluconate as the buffer. Gluconate is transformed into bicarbonate via all cells.

There has been some controversy that LRS should not be used in reptiles. The belief was that the lactate in LRS will exacerbate hyperlactatemia (acidosis) seen in dehydrated reptiles. The reality, however, is that reptiles use anaerobic metabolism and can tolerate high levels of plasma lactate. Therefore, the lactate salts in LRS do not affect plasma lactate levels (unless there is end-stage liver disease, in which case you would never use LRS regardless of the species being treated).

There is no one fluid that is universal for all reptile patients. Fluid choices should be based on laboratory sampling and electrolyte analysis. If an animal has mild dehydration, normal drinking should suffice. If it is severely dehydrated, veterinary help should be sought regardless of the cause.

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (REPTILE/AMPHIBIAN), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.