A parasite is any animal that lives on or within a second animal, and for the most part, parasites live in harmony with their hosts in the wild. They

A parasite is any animal that lives on or within a second animal, and for the most part, parasites live in harmony with their hosts in the wild. They derive sustenance or protection from them, and although they may not offer any benefit in return, this delicate balance between parasite and host in the wild takes on new meaning in captive reptiles. In some cases, a parasite that would not normally harm its reptile host in the wild can cause deadly disease in captivity.

In the wild, where an animal is not confined within a small space such as a cage, parasites are not found in high numbers, and the parasite burden to a reptile host is usually low. If the parasite is present in high numbers it may be harmful, and in captivity, especially in dirty cages, the concentration of parasites can be much higher, and hence, more dangerous.

For the most part, it is simple to diagnose parasite infections in reptiles, using a fresh fecal sample (not one that has dried on the bottom of a cage, been baked on a hot rock, or drowned in a water bowl). Keepers can collect a fecal sample and preserve it by placing it in a re-sealable plastic sandwich bag. This bag should then be placed inside a second sealed bag. If kept refrigerated, the sample will remain diagnostic for at least 24 hours. Most common parasites are readily diagnosed with microscopic analysis of the feces. However, some parasites, such as Cryptosporidia, require special stains (Acid Fast) or tests (PCR).

douglas mader, DVM

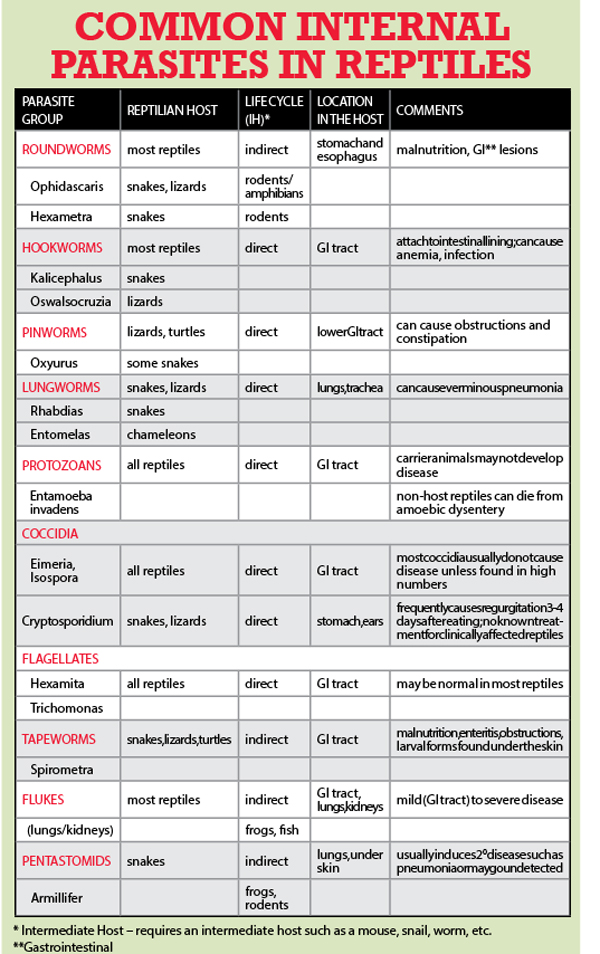

Common reptile parasites and the hosts in which they reside.

Reptile parasites have varying life cycles and affect different parts of the anatomy within the host. Some live in the intestinal tract and compete for nutrients, but do nothing more. Others, such as the hookworm, attach to the lining of the intestinal tract and feed off the host’s blood. This can cause serious damage, and in captivity, where the numbers of hookworms within a host can increase due to poor housing, it’s possible for a hookworm to actually kill its host.

douglas mader, DVM

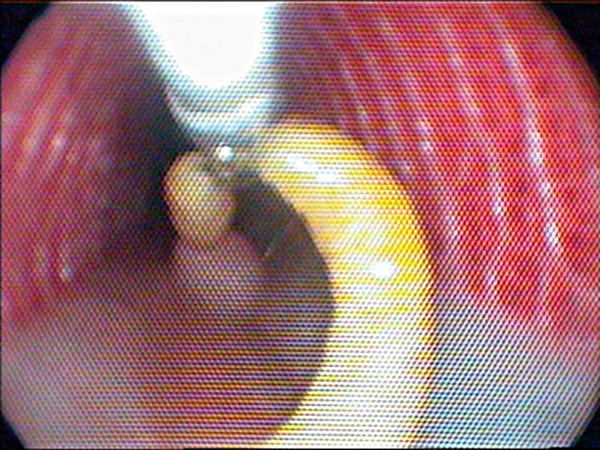

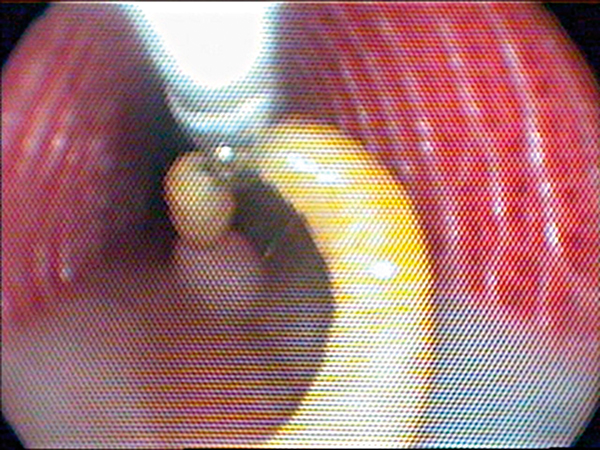

A pentastomid parasite in the lung of an indigo snake. The worms are removed using an endoscope, one worm at a time. (Note: Endoscopic images such as this are generated by flexible endoscopes and are normally pixelated as you see here).

Knowledge of a parasite’s life cycle can help you eradicate it from a reptile’s environment. For instance, the hookworm has a direct life cycle. It passes from one snake to the next, or back to itself, either via food that has been in contaminated by infected feces, or by direct contamination and infection through the skin (as happens when a lizard steps in infected feces within its cage)—just two of the many reasons why cages should be clean at all times.

Medical treatments vary depending on the type of parasite involved, and because of the anatomical location where some are found, treatment may not be possible. Thorny-headed worms, for example, may live in various locations throughout the abdominal cavity, but in general, they do not harm the host. Because parasiticides may not be effective at some locations where these parasites are found, and because they pose little risk to the host, thorny-headed worms are often not treated.

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.