Fractures in captive reptiles are common and are almost always secondary to some form of metabolic bone disease. Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroi

Fractures in captive reptiles are common and are almost always secondary to some form of metabolic bone disease. Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism (NSHP), which is a general lack of dietary calcium, excessive phosphorus or deficiency in exposure to ultraviolet light/vitamin D3 is the most common (another term for this condition is nutritional metabolic bone disease, or NMBD).

Read More From Dr. Mader

How to Recognize and Prevent Medical Ailments in Amphibians

The Vet Report: Sulcata Tortoise Spine Abnormality

The Vet Report: Fluid Therapy in Reptiles

The Vet Report: Inclusion Body Disease

Douglas R. Mader

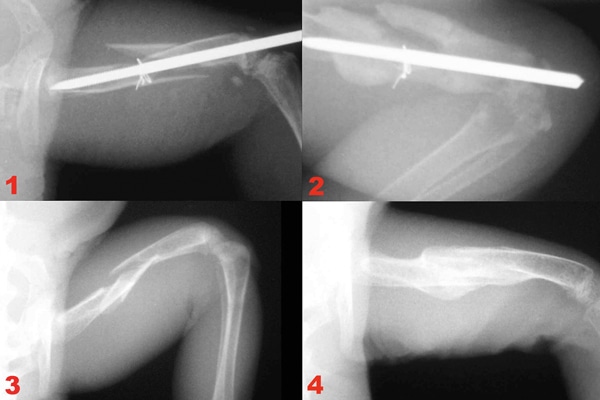

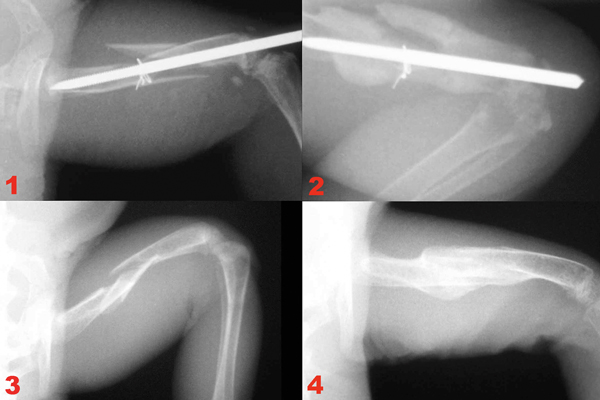

(1) An IM pin and orthopedic wire were used in an attempt to repair a comminuted femur fracture in this green iguana; however, the patient had uncontrolled NMBD and the fracture did not heal correctly (2). This broken thigh bone in another iguana (3) was treated with a combination of dietary correction and an external splint, leading the bones to heal completely after three months (4).

Leg fractures are rarely compound or comminuted—meaning they are usually not in multiple pieces or breaking through the skin—so most are readily treated with external coaptations (splints). Additionally, because most fractures are associated with demineralization and softening of the bones secondary to NMBD, repair with intramedullary (IM) pins or bone plates typically does not work well.

Regardless of a fracture’s cause, nutrition and diet should be thoroughly evaluated and corrected, and before attempting any fracture repair calcium homeostasis should be established. Otherwise, healing will not progress effectively.

Little information is available on fracture healing in reptiles, and no controlled studies have been conducted. Most of the information available comes from anecdotal reports relating to NSHP treatment successes and failures. It is generally accepted, however, that reptilian bone heals slower than mammalian bone, requiring two to 18 months for fractures to completely heal.

Considerations when deciding upon the type of fracture repair include the patient’s functional requirements (e.g., is the patient a pet lizard in a terrarium or a Komodo dragon about to be returned to the wild?), cost limitations set forth by the owner, the availability of the required materials and the experience of the veterinarian.

Most long-bone fractures, such as a leg fracture, will heal in time with nothing more than simple splinting, strict cage rest and the correction of any nutritional deficits. Although there may be some severe malunions in which the bones don’t heal perfectly straight, such complications do not seem to affect captive reptiles in an adverse manner.

The patient’s size may also dictate the type of fixation required. Large, heavy-bodied lizards and turtles may require internal fixation, for instance, whereas small, delicate lizards may do fine with only a light splint. The general condition of an animal, too, often plays a role, as it is physically impossible to utilize any type of internal fixator in many NSHP animals because their bones are not physically strong enough for an implant to gain purchase.

Which Fixation Technique Should Be Used?

External coaptation utilizes splints, casts or other techniques to immobilize a fracture. This is by far the most common technique used in reptiles.

In general, the best splints/casts are lightweight and comfortable for the patient. The animal’s activity must be restricted for best results, and a pet should not be permitted to run around inside a large cage, or climb and jump, during healing. Once calcium homeostasis is corrected improvement typically progresses rapidly, with the first signs of fracture healing showing on x-rays after about four weeks (re-checking x-rays prior to four weeks is a waste of time and money). Splints/casts can be easily applied to any of the long bones in lizards. The joints both above and below the broken bone should be immobilized to help ensure proper healing.

Chelonians can also be splinted, but because they live inside a rigid shell that does not permit ready access to their limb bones, modifications in technique are required. It is usually not possible to apply a splint to broken long bones (humerus/femur); instead, these must be re-aligned (with sedation/anesthesia as needed) prior to being taped into the leg opening in the shell until healing occurs. Splints/casts do not provide rigid fracture fixation as does an IM pin or bone plate. As a consequence, healing is not as rapid as it would be with a plate or external fixation device. However, the bone will still heal.

Internal fixation (e.g., IM pin, bone plate) is warranted for long-bone fractures in reptiles when splinting is not a practical option. Large, heavy, active and/or otherwise healthy reptiles with traumatic fractures that are not related to NMBD typically do well with internal fixation. In general, bone plates do not need to be removed, but IM pins should be once the fracture has healed.

As with anything related to veterinary medicine cost is often the deciding factor in final determination of fixation technique. Internal fixation carries a higher price tag due to the cost of the materials, the time necessary for application and the training of the surgeon. Because of this, although internal fixation may be the best for some patients, it is not always an option.

When a reptile suffers severe tissue trauma, loss of blood supply or infection to an injured limb, fracture repair may not be a viable option. Instead, amputation of the limb might be considered, as reptiles can usually manage quite well with three limbs, and amputation of digits or limbs can be accomplished with excellent cosmetic and functional results.

Douglas R. Mader, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.