Frogs in Panama adapting and surviving chytrid fungus infection.

In 2004, biologists in El Copé, Panama, observed frogs dying by the thousands as a result of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, the fungus also known as chytrid. Within months, around half of the frog species in the locality where the die off occurred were declared locally extinct.

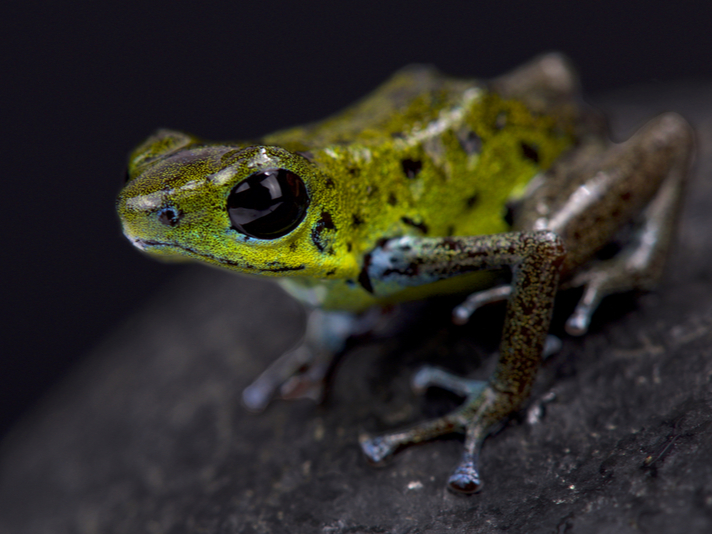

reptiles4all/Shutterstock

Green strawberry dart frog (Oophaga pumilio).

That extinction spurred scientists with Michigan State University to study the site where the mass extinction occurred. They determined that the remaining species of frogs that were found in the locality learned how to survive and coexist with the fungus. That study, "Eco‐evolutionary rescue promotes host–pathogen coexistence," published in the Ecological Society of America, shows potential promise for frog populations devastated by Bd.

Golden Poison Dart Frog Care Sheet

“Our results are really promising because they lead us to conclude that the El Copé frog community is stabilizing and not drifting to extinction,” Graziella DiRenzo, the lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at Michigan State University told MSU Today. “That’s a big concern with chytrid worldwide. Before this study, we didn’t know a lot about the communities that remain after an outbreak.”

DiRenzo and her colleagues studied the 2-square-kilometer field site from 2010 to 2014 and repeatedly sampled the frogs in the field site for Bd and concluded that frogs infected with the fungus were surviving at the same rate as those amphibians that were uninfected. This led the researchers to believe that those infected frogs were able to develop the capability to live with the fungus and survive the devastating effects that usually occur when amphibians are infected with it.

The researchers say that the frogs living in El Copé have learned to survive because of an effect that is called “eco-evolutionary rescue,” whereby some species that survived the spread of Bd and other species died off, killing the chance for the fungus to further spread. Those that survived learned to adapt evolutionarily. This is potentially good news for other frog populations around the world that have been negatively affected by the chytrid fungus.

“The frogs of El Copé are not doing great, but they’re hanging on. The fact that some species survived is the most important thing,” said Karen Lips, University of Maryland biology professor and co-author. “If enough frog species in a given place can survive and persist, then hopefully someday a vibrant new frog community will replace what was lost.”