Leopard lizards are alert, capable of Mach-1 speed and bipedal during evasive maneuvers.

Leopard lizards are alert, capable of Mach-1 speed and bipedal during evasive maneuvers. Opportunistic in habit, they are predators of the highest esteem and cannibalistic when hunger dictates. In a nutshell, they are replicas directly out of Jurassic Park.

As the common name implies, and with a bit of colorful imagination thrown in, members of the genus Gambelia somewhat resemble real leopards. But some, such as blunt-nosed (G. sila) and to a lesser degree Cope’s leopard lizards (G. copeii), definitely do not resemble their namesakes where pattern and color are concerned. However, they all practice similar leopardlike habits of stalking prey by “jumping” into the air to secure a worthwhile morsel. And when cornered and/or handled they show considerable malevolence — a well-placed bite by an adult leopard lizard is a painful encounter.

Karl-Heinz Switak

Leopard lizards are incredibly agile reptiles.

Range and Habitat

Four species of Gambelia (formerly Crotaphytus) have been described: Cope’s (Gambelia copeii), blunt-nosed (G. sila), long-nosed (G. wislizenii) and Lahontan Basin leopard lizards (G. w. maculosa). The latter is not mentioned as such by Stebbins (2003), but referred to by St. John (2002), who puts it perfectly when he writes: "Depending on the authority consulted …. "

Leopard lizards range over a large area of the United States, northern Mexico, much of the Baja Peninsula, plus several Pacific islands and Isla Tiburón (a large island in the northern part of Mexico’s Gulf of California). More specifically, they occur in all four major North American deserts (Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan) ranging from central Idaho in the north to Zacatecas, Mexico, in the south.

Stebbins (2003) states that they range from near sea level to around 6,000 feet. However, any specimens that may be roaming near the Salton Sea in California, or points farther south and southeast, would in fact be doing so below sea level. I found a specimen east of El Centro, California, which is 40 feet below sea level, in the early 1960s. It was more than likely living at or just below sea level. Pickwell (1972) pictures a long-nosed leopard lizard found in Death Valley (most of the valley floor is below sea level). So it is possible that Pickwell’s specimen was found at or below sea level too.

Because of this enormous range in elevation, leopard lizards frequent many different microhabitats. They avoid densely vegetated regions, however, because it interferes with their ability to give chase and efficiently subdue prey. Some of the plants found in Gambelia domain include creosote, sagebrush, greasewood, alkali bush, bunch grass, manzanita, live oak and flat-top buckwheat.

Captive Care

I don’t recommend Gambelia for the beginning hobbyist. But if you are interested, you should first research the habits of your captive-to-be before making the commitment. Many fine publications are available for this purpose. If the temptation to keep one of these stately reptiles becomes unbearable, then here are a few pointers to follow.

Karl-Heinz Switak

Leopard lizards, in their natural environment, love the sun.

Leopard lizards are diurnal, territorial, solitary by nature (except during the breeding season) and definitely pugnacious. Keeping a single adult in a terrarium less than 3 feet by 2 feet by 1 foot tall is doing it a great injustice. Commercial animal dealers often house dozens in extremely close and deplorable confinement, surely stressing the usually solitary lizards.

Provide a hot spot in the terrarium that reaches about 85 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit during the day, then allow it to drop into the mid-60s at night. Make certain that not every square inch of living space is exposed to this high temperature.

At least some exposure to ultraviolet light, either direct or via commercial sun lamps, is necessary. Remember, the beneficial rays of the sun are filtered out through ordinary glass. In the wild, leopard lizards are sun worshippers of the highest magnitude.

For a cage substrate use gravel mixed with sand and even some leaf litter. Also add several large rocks, but make absolutely certain these are positioned in such a way that no collapse can take place when a lizard tries to excavate underneath.

If you have the space to keep these lizards in an outdoor pen, then make sure it is securely covered with quarter-inch screen, lest you care to offer your captive to a raucous crow, jay, magpie or other avian predator. Cats and raccoons are also lizard thieves and certainly good climbers.

Remember to offer your captive a variety of food items. Leopards readily take crickets, grasshoppers, waxworms and the occasional newborn mouse; stay away from using mealworms. From time to time you must also offer smaller lizards as food. When doing so be sure and first remove any visible ticks and mites from lizard prey.

Water is of no great importance; much of the leopard’s liquid requirement is obtained from the food it eats. However, they will lap water off large leaves and depressions in a rock. It’s OK to place a shallow water dish into the cage once a week, but remove it several hours later. Gambelia are efficient excavators and always looking to dig a hole here and there, thus covering the water dish quickly with their mining activities.

Lizard Killers

Leopard lizards are primarily ambush predators. That is, they normally remain motionless at the edge of vegetation until prey approaches within striking distance, at which time they charge out with lightening speed and proficiently overpower unsuspecting insects or smaller lizards. There are exceptions, however.

Many moons ago, I was visiting the expansive Algodones Sand Dunes, lying between El Centro and Yuma, Arizona, in an attempt to try and photograph a large whiptail lizard (Cnemidophorus) in the dappled shade of a creosote bush and with a glint of sunlight reflecting in its eyes. This desert region, better termed an inferno during the summer months, boasts large expanses of creosote bushes and plenty of rodent burrows, and is a great location to view a number of interesting lizard species.

I parked my vehicle well off the road, secured my camera gear in one hand and a lizard snatcher in the other. Within seconds an adult whiptail ran across my path — and ran and ran. Lizards two through 10 behaved in an identical fashion.

Finally, an hour later and with rivulets of sweat running down my body, I found my quarry in the most opportune location, but it wouldn’t hold still. I followed it from one creosote bush to another until it finally stopped and posed perfectly. I elevated the camera and took aim, but before I could trigger a single frame, a dash of lightening appeared out of nowhere, grabbed "my" whiptail at midbody and charged off into the distance. The culprit: a large long-nosed leopard lizard. I gave chase, if only to see if the leopard held on to the whiptail (which it did), but my pathetic gait across the loose soil proved futile.

Lee Grismer, in his excellent book Amphibians and Reptiles of Baja California (2002), recalls two noteworthy feeding habits pertaining to Gambelia that are certainly worth mentioning here.

The first encounter involved a Cope’s leopard lizard near Cataviña, Baja Norte. It was emerging from a burrow in the early morning with the feet and tail of a zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) protruding from its mouth. Lee surmised that this leopard began eating its prey the previous day, but could not fit all of it in its stomach at one time. The other Grismer example involved a female long-nosed leopard lizard from Isla Tiburón. This specimen measured 4.3 inches in snout-to-vent length (SVL) and was coaxed to regurgitate a whiptail (Cnemidophorus) with a SVL of 4.2 inches.

Karl-Heinz Switak

Leopard lizards are among the most cannibalistic species.

Alan St. John (2002) and his friend Craig Zuger found a large female long-nosed leopard lizard near Pyramid Lake, Nevada. It was holding a small- to medium-looking zebra-tailed lizard crosswise in its jaws. After at least 20 minutes, the Callisaurus was swallowed headfirst.

Ronald Nussbaum, Edmund Brodie, Jr. and Robert Storm (1983) mention a 102-mm-long (SVL) long-nosed leopard lizard that ate a 71-mm-SVL whiptail lizard (Cnemidophorus tigris). They reported that another leopard apparently choked to death on a whiptail measuring 80 mm.

Quite a few lizard species are recorded by various authors as falling prey to Gambelia. I believe the best way to sum it up is to quote Hobart Smith out of his excellent work, Handbook Of Lizards (1967): "This species is actually one of the most cannibalistic known in this country [USA]. They eat specimens of their own species and Uta stansburiana, Sceloporus graciosus, S. u. consobrinus, S. magister, Holbrookia maculata, Callisaurus draconoides, Cnemidophorus tesselatus and Phrynosoma platyrhinos [desert horned lizard]."

Van Denburgh (1922) also mentions Phrynosoma as a prey species of leopard lizards, but doesn’t go into details nor identify which horned lizard. Regardless of the variety implicated, it was more than likely a very small individual. No self-respecting reptilian leopard would have the slightest difficulty in overpowering and ingesting a hatchling or young horned lizard. Swallowing an adult, however, would border on the realm of impossibility.

Horned lizard expert Wade Sherbrooke (1981) puts it this way: "Leopard lizards kill narrow-bodied lizards and swallow them whole. They will eat juvenile horned lizards, but are not likely to attack the broad-bodied adults."

Bob Applegate has found Cope’s leopard lizards in close proximity to coast horned lizards (Phrynosoma coronatum). Dale Sylvester, a colleague of mine, and I have seen a coast horned lizard enter a burrow used by blunt-nosed leopard lizards. It is likely that this horned lizard species does occasionally fall prey to both of the aforementioned Gambelia species.

Not Only Lizards

Leopard lizards also eat a tremendous amount of insect species, including grasshoppers, beetles, caterpillars, butterflies, termites, bees, wasps, crickets, cicadas, flies and many more. Spiders have also been recorded in their diet. Even some plant material may occasionally be ingested, such as tender leaves, blossoms and berries.

Stebbins mentions that "snakes and rodents (pocket mice)" are also eaten. Unfortunately, the serpent variety is not identified. S.M. Secor (1994) suggests that leopard lizards could possibly feed upon very small sidewinders (Crotalus cerastes). I would give my right arm (almost) to see a large leopard lizard attack, kill and then swallow a neonate snake of any kind.

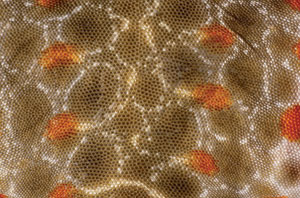

Karl-Heinz Switak

The spots of a leopard lizard.

Some of the smaller snake species that abound in Gambelia habitat include night snakes, sand snakes, ground snakes and ring-necked snakes. Hatchling Coluber, Masticophis or Thamnophis might also be included in the Gambelia diet, as all three are diurnal.

Hunting Machines

Because of a leopard lizard’s speed and cunning, very little escapes its watchful eye. If it doesn’t catch prey with its wait-and-ambush tactics, then it simply runs it down or even jumps high into the air for the final blow.

Many things have been said regarding the hunting prowess of leopard lizards. One witness saw a leopard lizard jump 4 inches off the ground (all of its feet left the ground) and snatch the fly out of midair. In another account a leopard lizard was observed running swiftly and directly below a grasshopper as it flew about 2 feet above the ground. Someone else reported seeing a leopard jumping 2 feet into the air to catch a cicada.

To further exemplify the agonistic attitude and strength of leopard lizards, I recall an instance involving a blunt-nosed leopard lizard. While observing an adult meandering from one small bush to another during early spring, with plenty of grass cover in all directions, another adult appeared with lightening speed, grabbed the lizard that I was watching at midbody and then charged off with it for at least 20 feet.

From what I could make out, although it all happened in mere seconds, bipedal locomotion took place and the lizard being carried was held well off the ground. Once the lizards came to a full stop, one released the other, and they immediately took off in different directions. I am not going to hypothesize if this behavior was a premating activity or simply movement in the grass that was construed as potential prey by the attacking lizard. However, it does illustrate Gambelia’s lightening-quick attack, the brute strength of its jaws and the power of its hindlegs.

Feisty From the Start

Leopard lizards are egg layers, depositing two to six eggs per clutch (estimates vary greatly among authors). In the southern parts of their range, a second clutch is possible. The eggs are laid between March and July, depending on local weather conditions. Young hatch in August or even early September, with weather conditions (favorable or inclement) and locality (northern or southern) playing a deciding hand.

Grismer reports having observed hatchlings of G. wislizenii during mid-July near the Sierra San Felipe in Baja. I found hatchlings and young of G. wislizenii (maculosa?) just east of Cedarville, California, on September 9. My nephew Ian Zimmermann and I found hatchlings of G. sila on August 13 on the Carrizo Plain of California; they may have already been 1 week old. One of these wedged itself under our parked car’s front tire near the edge of a dirt road. We tried chasing it out with a long stick, but to no avail. Under no circumstances was I going to move the Jeep with our prize still in the same place.

So we abandoned the stick, and Ian tried to remove it by pointing his finger toward the lizard’s head. Bingo. It lunged forward, latched onto his finger, bit down forcefully for such a small beast and ran off into a nearby bush. It seems that the leopard’s defiant attitude commences almost immediately upon hatching.

Cannibalism

Known to be cannibalistic, why don’t adult leopard lizards eat all of their offspring? Surely, they don’t instigate a self-imposed plan that limits the amount of hatchlings they can overpower? I think not!

Based on my and others’ personal observations, it appears that the adults are not active when the young hatch. This opens the door for the neonates to roam freely, take advantage of every insect meal in the neighborhood and thus add a considerable amount of size before meeting up with "big brother."

When I found the hatchlings east of Cedarville, no adults or even subadults were present — not in the morning, not during the day and not prior to sunset. When Ian and I observed the G. sila hatchlings on two consecutive days, again no adults were seen during any temperature gradient throughout each day — only hatchlings.

Taking it one step further, I’ve never seen adults and hatchlings/young active at the same time of the year nor in close proximity to each other. Smith wrote: "Numerous authors have mentioned observing young specimens in August and September, but only large specimens during June and July." Obviously the system works, as many hatchlings reach maturity.

It’s always better to leave wild reptilian leopards where you find them. Enjoy their magnificent presence in nature, not in the restricted confines of captivity. However, anyone still wishing to keep one should take the time to read this article’s captive-care sidebar.

References

Grismer, L. 2002. Amphibians and Reptiles of Baja California. Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkely, California.

Nussbaum, R., Brodie, E. Jr. and Storm, R. 1983. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Univ. of Idaho Press, Moscow, Idaho.

Pickwell, G. 1972. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific States. Dover Publications, New York, New York.

Secor, S.M. 1994. Natural History of the Sidewinder (in Herpetology of the North American Deserts). Southwestern Herpetology Society, Van Nuys, California, Publication #5.

Sherbrooke, W. 1981. Horned Lizards. Southwest Parks and Monument Assoc., Globe, Arizona.

Smith, H. 1967. Handbook of Lizards. Comstock Publishing Co., Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, New York.

Stebbins, R. 2003. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, New York.

St. John, A. 2002. Reptiles of the Northwest. Lone Pine Pub., Renton, Washington.