IBD Blood Test Developed for Pythons and Boas

While Florida busies itself trying to eradicate non-native pythons in the Everglades, researchers at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine want to help pet pythons and boas through a blood test for inclusion body disease (IBD).

IBD is highly infectious and usually fatal, primarily affecting boa constrictors and pythons. While snakes with IBD may display signs such as head-tilting, chronic regurgitation or disequilibrium, the problem—and the primary reason for the test—is that some infected snakes exhibit no signs and appear healthy.

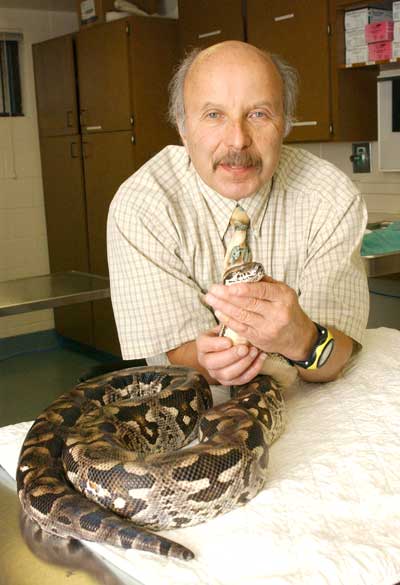

Dr. Elliott Jacobson with a Dumeril’s ground boa, one of the species prone to IBD.

The disease emerged in the reptile trade in the late 1970s, said Elliott Jacobson, DVM, Ph.D., Dipl. ACZM, a UF professor emeritus of zoological medicine and co-author of a study announcing the test. The article appeared in the December issue of PLOS ONE, an online scientific journal.

“We don’t know the prevalence, but we see more of IBD in the United States because there are some 2 million boas being kept as pets in this country,” Dr. Jacobson said.

“This simple blood test will help determine whether or not an animal has this disease and potentially will help clean up colonies of snakes that will ultimately be disease-free,” he added.

Being able to identify infected snakes that show no symptoms is key.

“Healthy-seeming animals that are affected with IBD are being sold and sent around the world,” Jacobson said. “However, they may develop the disease sometime later and may be the source of infection for other snakes.”

Among the other members of the research team that developed the IBD test were principal investigator Li-Wen Chang, BVM., Ph.D., and veterinary epidemiologist Jorge Hernandez, DVM, Ph.D., MPVM. To develop the test, the researchers studied a monoclonal antibody produced in response to a unique protein that accumulates in cells of snakes with IBD.

“It took us almost a year to finally produce this antibody, and three more years to validate its performance for immuno-based diagnostic tests,” Dr. Chang said.

Though IBD’s cause is unknown, the researchers found that genetic links of the unique protein are associated with a family of viruses that primarily infect rodents. The test is offered at the Gainesville, Fla., institution’s Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research through the university’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratories. For now, the test will supplement existing molecular and histological analyses, which are more widely available but more expensive, Jacobson noted. In addition, the test’s ease of use and simplicity will offer veterinary practitioners a good first-line diagnostic tool to screen for IBD in snake species that show signs of the disease or even those that don’t.

“We know now that this disease exists in multiple collections and populations,” Jacobson said. “It’s a situation of management. You’ll never completely eradicate this disease.”

The American Association of Zoo Veterinarians’ infectious disease committee recommends the quarantine of newly imported snakes, the culling of infected snakes and mite control as the best ways to control IBD’s spread.