In beardies, aneurysms can occur in many different locations.

Over the past couple of decades, bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) have fast become one of the most popular reptile pets kept in captivity. As with anything, when you start seeing more numbers, you start to see and learn more about the subject.

Douglas mader

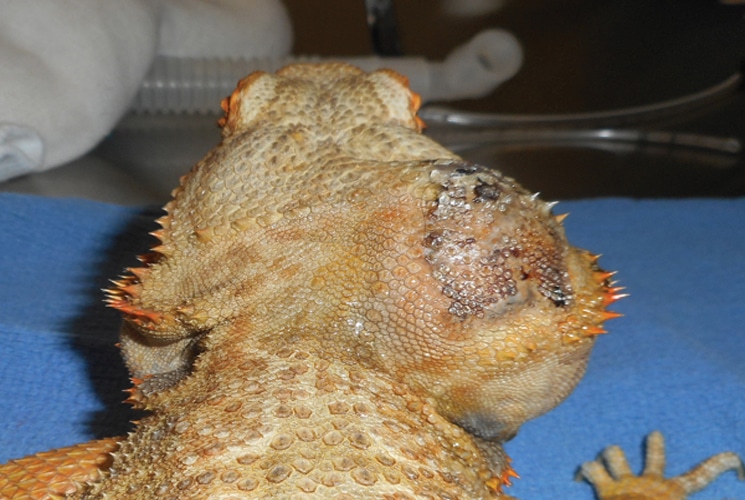

Caudal view of the patient’s head showing the large cephalic aneurysm just behind the jaw on the right side.

I remember more than 30 years ago examining beardie patients, and the main medical problem was dehydration, a condition common in recently smuggled dragons that were brought into the United States, having been confined in improper shipping boxes for several weeks all the way from Australia. Now, with the huge numbers of bearded dragons in captivity, I see all the common stuff like NSHP, parasites, fractures, viruses, bacterial and fungal diseases and more.

douglas mader

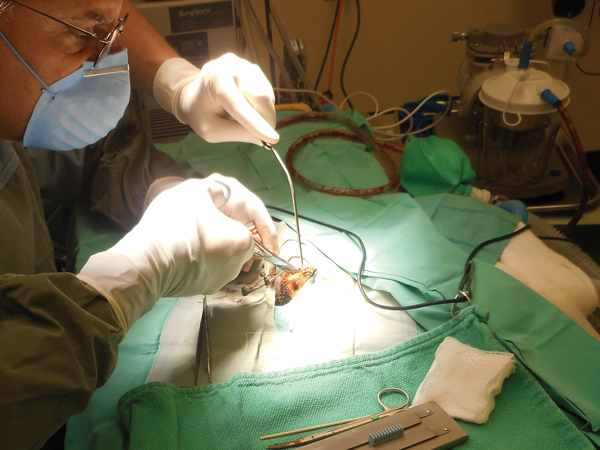

This X-ray shows the stainless steel vascular clip (arrow) over the leaking site of the internal carotid artery.

One of the more interesting medical conditions, referred to as “aneurysm syndrome” on the lay herp boards and chat rooms, has been seen with more frequency over the last 10 years. This condition, which generally carries a grave prognosis, has still yet to be fully defined.

douglas mader

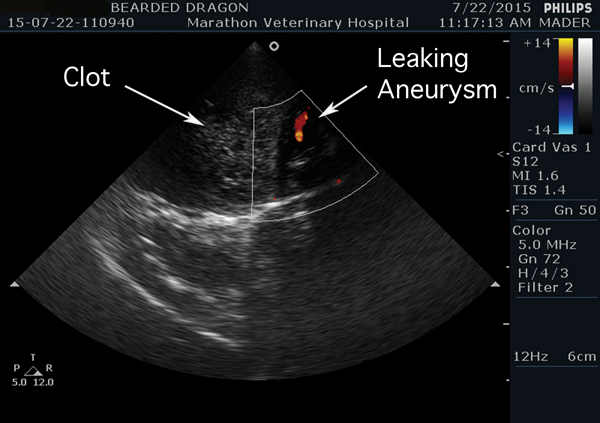

This ultrasound image shows both the large blood clot and blood leaking from the aneurysm in the internal carotid artery.

A quick Google search yielded several dozen amateur references to aneurysm syndrome. For the most part, all of them say something like, “no known cause, can’t be treated and most animals die within a few months of diagnosis.”

I have personally seen several dozen cases. Many other reptile veterinarians have also reported aneurysm cases, as well. By definition, an aneurysm is a localized enlargement of an artery caused by a weakening of the artery wall. Eventually these enlargements weaken to the point of bursting. Being an artery, or high-pressure vessel, these patients are at high risk of bleeding to death internally if they rupture. When a person has a bleeding aneurysm in the brain it can be lethal if not caught immediately.

In beardies, aneurysms can occur in many different locations. I have seen them on the limbs, over the hips, in the mouth and, most commonly, over the top of the head (cephalic aneurysms). During necropsy examinations (an animal autopsy) I have also seen bleeding into the pericardial sac, the fibrous lining around the heart. Whether or not this arises from an aneurysm or from a leaking heart muscle, I don’t know, but the gross appearance is similar.

douglas mader

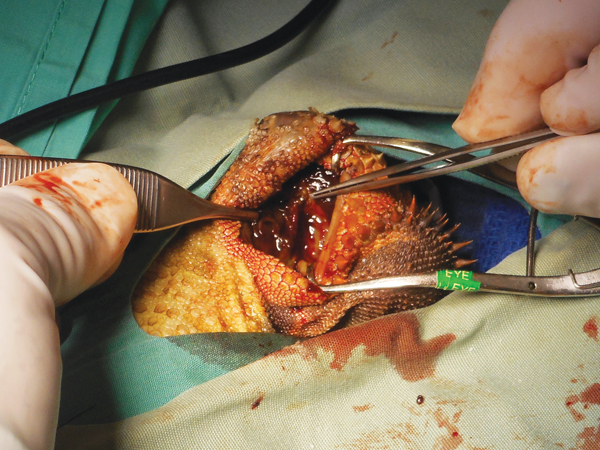

A radioscalpel was used to make an incision along the caudal margin of the head, just above the lateral spikes. The large blood clot under the skin was readily visualized.

There have been a few scientific reports of the cephalic aneurysms. In 2006 I co-presented a paper at the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians annual meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, with Drs. Jeanette Wyneken, Stephen Barten and Michael Garner. We discussed two cases of cephalic aneurysms including the presentation, necropsy findings (one animal died), the anatomy of the aneurysm and successful treatment of one animal that lived.

douglas mader

Constant suction was used to keep the surgical field clear of blood which provided better visualization of the inside of the head, thus making it easier to find the tear in the blood vessel.

Dr. Wyneken, a PhD anatomist, noted that both cephalic aneurysms arose from the internal carotid artery near its origin from the aorta. Dr. Garner, a pathologist, commented that the walls of the artery were fibrous and lacked the elasticity of the normal artery. Hence, the lack of compliance of the high-pressure vessel predisposes it to bursting and hemorrhage.

In the second of the cases we presented, the patient had an extensive diagnostic work-up prior to treatment. It underwent a thorough physical examination, laboratory analysis, X-rays, ultrasound and a CT scan with contrast agent. Once the location of the aneurysm was positively identified the animal was taken to surgery and a vascular clamp was applied across the leaky vessel. The patient experienced severe blood loss during the procedure but received a transfusion of bearded dragon blood from a healthy donor, and survived the surgery, living an additional several years. Although this patient did well, it should be pointed out that the efforts to diagnose and treat this animal were both extensive and expensive. Since that presentation, several veterinarians have started collecting data on this condition. There are summary papers in preparation that should hopefully shed more light on this frustrating disease.

douglas mader

The patient one day post op. It started eating the day after surgery.

I had a recent case of a cephalic aneurysm where the owner wanted to treat, but was not able to financially pursue all the diagnostics. Using the information that we learned from the previous cases, both alive and dead, I was able to take this patient to surgery, and using the same technique, was able to successfully find and stop the leaking from the internal carotid artery. As with anything, the more we see, the more we learn, the more we do, the better we get. Hopefully, with all the great intellects working on this serious beardie problem, we won’t have to perform dangerous surgeries to attempt treatment, but rather, we can figure out why bearded dragons develop the aneurysms and then prevent them from ever happening.

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.