Popular in the 1960s, the red eared slider was the poster animal for the mail order/dime store reptile

Like many other children born in 1960, my first real pet, a pet that was not the family dog, but my pet, was a baby red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Variety stores (often referred to as five-and-dime stores) supplied a great many baby turtles sold in the United States. These were predominantly red-eared sliders, but additional species, even non-native, such as the Amazon yellow-spotted side-neck turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), would periodically be offered. Typically costing only 25 or 50 cents during the 1950s and 60s, the red-eared slider became known as the dime-store turtle. Although this era was the heyday for baby pet turtles, my mother recalls purchasing a baby turtle in the early 1940s from S.S. Kresge (a five-and-dime store). She and her second-grade classmates were encouraged to bring their turtles to school, where races were held in the classroom.

Simon_g/Shutterstock

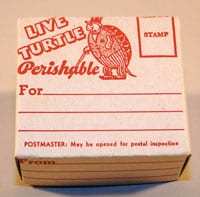

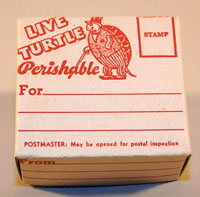

Baby aquatic turtles were available by mail order, packed in small boxes made specifically for the purpose, and sporting graphics and advertisements.

The red-eared slider is an aquatic species native to the U.S., inhabiting freshwater systems, and ranging from West Virginia to New Mexico and south to the Gulf of Mexico. The typical adult size is 5 to 8 inches in length. However, individuals over 11 inches have been recorded. Although these potentially long-lived pets rarely lived long enough to grow, that did not discourage their sale.

Popularity in Print

A 1937 Sunday comics newspaper page featuring a color Ralston Purina cereal, Tom Mix cartoon included a coupon for a free baby turtle. The promotional turtle's carapace was decorated with a painted Tom Mix Ralston Straight Shooter Bar Brand logo, and was mailed to children for two cereal box tops, or one box top and a 10-cent coin. Additionally, a 1950 full-color comic book advertisement offered kids "real, live racing turtles." For $1, Jamaica Pet of New York, mailed a baby turtle, with its carapace completely painted in your choice of five colors, along "with your favorite name on it," turtle food and a glass bowl.

Boxes with cellophane windows, measuring 4 inches long, 3 inches wide, and 1 inch tall were manufactured specifically to highlight and sell baby turtles, and allow for easy transport. These boxes were also used to sell "chameleons," which were in fact American green anoles (Anolis carolinensis). The box stated, "make ideal pets, live baby turtles; loads of fun for children, and hand-painted baby turtles."

A 1953 comic book advertisement aimed at children claims to have 1000 live baby turtles, and offers to include one free when purchasing a $1.69 (delivered) "Magic Rock Garden, which grows real grass and flowers in four days." Regarding the baby turtle, the ad states that: "every boy and girl loves these clean little pets. Delivered healthy and safe in a special moss-protected package." Additional text from the ad reads: "Here's one of the most exciting toys you've ever owned. Just think-a baby turtle all your own, and you can make a little house for him to live in."

Everything is included for a tiny (about 100-square-inch) rock garden, but absolutely no provisions or instructions are mentioned concerning the live, aquatic turtle hatchling. Many turtles died due to this type of setup.

It's In the Mail

Baby aquatic turtles were also available by mail order, packed in small boxes made specifically for the purpose, and sporting graphics and advertisements. The boxes were printed with sender and addressee areas, as well as a postage stamp placement graphic. The High Turtle Food Co. box measures 4 inches long, 2 inches wide and 1 inch high. It was supplied with ventilation holes and sported a large ad for their 10-cent-per-package food. In addition, various areas of the box sported the following information: "beautiful hand painted turtles a symbol of good luck, perishable live turtle, and no food necessary while shipping."

Another turtle food company (name not provided on the box) supplied live turtle mailing boxes measuring 2 inches long, 3 inches wide and 1 inch tall. Adorned with a comical turtle figure, standing upright, dressed in pants with a top hat and cane, a side panel reads, "pleeztomeetcha! Take good care of me! And I will live a hundred years." An additional panel provides directions, instructing one to feed specially prepared baby turtle food, 15 cents per package. It also states, that the turtle will eat only when water is at room temperature. During the dime-store-turtle era, this seems to be the only mention by any turtle food providers that temperature is important to baby turtle health. Of course, this ambiguous statement is of little real benefit to the turtlekeeper.

Turtle Toys

Pet baby turtles were so popular that Animate Toy produced the "Baby Turtle," a nicely detailed, fairly accurately colored and patterned, tin lithograph friction toy turtle. Its colorful designs were applied onto tin-plated steel through a process known as chromolithography. Printing in the interior of the box claims "Raised in the U.S.A." and provides the common and scientific name of the baby turtle, as well as the geographic region it inhabits. Although they claim to have produced a series of the turtles, and they do list different species in their boxes, I'm skeptical the toy company had more than a single design, which is unmistakably a red-eared slider. The toy turtle's shell measures an inch long, and when pushed along a surface, the paired front and rear legs and feet move independently in an alternating fashion.

Death Traps

The stores selling baby turtles also stocked small, plastic enclosures known as a "Turtle Lagoon." These bowl-like enclosures were typically kidney shaped, with a ramp exiting the water reservoir and ending at an island, complete with a green plastic palm tree. Turtle Lagoons are manufactured today, but I believe they are reproductions of the early models. Although they evoke nostalgia for those of us old enough to have owned dime-store turtles, the enclosures are not adequate for raising even a single aquatic turtle. All species of hatchling turtles will quickly outgrow even the largest of the various size lagoons, which measures only 14 inches long, 10 inches wide and 3 inches deep. Additionally, this enclosure does not allow for proper heating and basking devices to be added.

Dietary Disaster

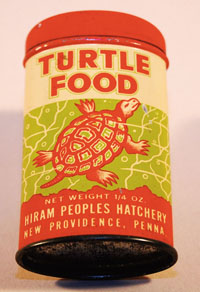

The food sold at dime stores was no better than the enclosures available. Early commercially prepared diets were sold in tin containers sporting colorful graphics and displaying a generic, often comical, turtle design. The earliest examples are probably the round tin containers. These measured 2 inches in diameter, and the turtle food contained within was sold by companies such as Auburndale Goldfish of Chicago, Ill., and E.C Vahle Co. (America's oldest bird dealers) of Philadelphia, Pa.

The most common early lithographed tins, circa 1950s, were an oval shape, 3 inches tall, typically with removable lids, and contained 1/4 or 3/8 ounces of food. Many companies, such as Hiram Peoples Hatchery, New Providence, Pa., American 3 Vees, American Bird Food Manufacturing Corporation, Chicago, Ill., and Hartz Mountain Products, New York, sold these early foods. Hiram Peoples Hatchery food consisted of only dried flies, and instruction on the reverse of the can read: "when feeding, raise water to depth of about an inch." American 3 Vees food ingredients were dried larvaes, shrimp and meat meal. Instructions stated, "once in a while, a small piece of lettuce or tomato should supplement the food." Hartz Mountain food was made from ant eggs and dried flies, and also mentions the supplementation of lettuce or tomato. A rare 3 Vees tin, rectangular in shape, with rounded corners and a "knock-out plug" in the top, is wrapped in a paper label. The turtle graphic is the most detailed of the era, but to my eye, appears to resemble a tortoise crossed with an aquatic turtle species. The half-ounce contents are wheat, meat and bone, and ground flies.

Slightly later tin containers, circa 1960s, were squat and rectangular in shape, and provided a sliding, or press-fit plug top closure. Hartz Mountain and 3 Vees continue to market food in this era. The Hartz tin container featured a detailed rendering of a red-eared slider. During this era, Hartz published a booklet titled Pet Care, and devoted nearly an entire page to the care and feeding of turtles. An image of their turtle food, along with a baby aquatic turtle adorned the page, but little pertinent husbandry information was provided. Manufactures, such as Wilot and Company, Chicago, Ill., sold ant eggs and dried flies under the name Wilot's Turtle Food, packaged in a colorful rectangular cardboard container.

During the mid to late 1960s, the tin and rectangular shaped containers were replaced with cylindrical cardboard containers, with rotating, plastic disk shaker tops. Companies such as Permalife, distributed by Aquarium Supply Company, division of Sternco Industries, Inc., Harrison NJ, and Delta Products, Division of Sternco Industries, Inc., Allendale, NJ marketed turtle food. Many containers were adorned with red-eared slider turtle graphic, and the 1/2 , 3/4 and 1 ounce (probably from different time periods) cost 19 cents. Although sold as turtle food, the containers stated that it was prepared especially for water lizards, chameleons, small alligators and turtles. The ingredients of some were fish meal, beef meal, dried flies and sometimes requegon. Feeding bits of ground beef and green lettuce leaves was also instructed, as well as weekly enclosure water changes. Others contained a mixture of corn meal, fly larvae, wheat middlings, beef liver, soybean meal, calcite, alfalfa meal and animal fat preserved with BHT. Apparently, the additional ingredients negated instructions of supplemental food, as none are mentioned. Sold in 1-ounce plastic bottles, retailing for 29 cents, Permalife also produced Turtle Bath. A supposed shell malady remedy, it consisted of greatly diluted sulphathiazole sodium and urea.

Still Popular, but Now Better Cared For

I was 5 years old and my sister a year older when our first two pet turtles were presented to us. Typical of most adults, my parents relied on the care information provided by the seller. This consisted of housing the two hatchlings in the small plastic Turtle Lagoon, and feeding the inadequate food from the tiny container. Like the vast majority of the dime-store turtles, ours did not live to adulthood. Retailers made no mention of required supplemental heat for our Chicago home. Nor did they hint at the potential size a pair of red-eared sliders might reach, and the necessary equipment required to raise the growing chelonians.

Hatchlings that were mailed would succumb to dehydration or temperature extremes during transit. Turtles purchased for unsupervised children were neglected, fed inadequate diets, endured contaminated water in their undersized plastic enclosures, and were rarely provided the necessary heat for survival. Additionally, products such as Wardely's (Wardley's Products Co., Inc. Long Island City, N.Y.) sold 1/2 ounce bottles of "Turtle Tank Freshener" with hexachloraphene (an antibacterial agent) with baby turtles. Instructions stated to add just a few drops a day to the enclosure water. This may have postponed badly required frequent complete water changes, allowing bacteria to flourish.

In the '70s, the Food and Drug Administration investigated the issue of children contracting Salmonella from turtles, and in 1975, they banned the sale of turtles with a carapace less than 4 inches. The FDA claims the ban prevents 100,000 children a year from becoming infected.

Thankfully, not all dime-store turtles perished as babies. The Cleveland Aquarium (Ohio) operated from 1954 to1985. During its service, it maintained an impressive display devoted entirely to turtles donated by the public. After recently corresponding with the former curator of the facility, he recalled the exhibit measuring roughly 18 feet wide and 12 feet front-to-back, with a waterfall, and approximately one-third of the floor consisting of a shallow (around 8-inch) pool. The exhibit held approximately 70 turtles, virtually all donated red-eared sliders; a Louisiana heron was a cage mate.

Red-eared slider popularity has not diminished. Today, the vast majority of commercially manufactured aquatic turtle diets continue to feature this species on the label or packaging. I have fed Reptomin to my aquatic turtles for more than 20 years, and although most, if not all, modern commercial diets provide well-rounded nutrition, I never rely on them solely. I also feed whole fish of the appropriate size or cut up, earthworms, night crawlers, waxworms, crayfish and crickets.

There are a number of responsible turtle breeders and sellers producing and selling quality aquatic turtle hatchlings. Nutritious, commercially prepared diets from various producers are widely available, as are appropriate enclosures, filters and required accessories. Additionally, there is informative literature detailing the captive husbandry of baby turtles, as well as several books dedicated exclusively to the care of red-eared sliders. However, just because information is available does not guarantee it will be utilized. To illustrate this, my most memorable example comes from a reptile show in Cleveland where I was a book vendor. A middle-aged gentleman holding a deli-cup container, with several recently purchased hatchling red-eared sliders, approached and asked if I had a book on their care. I responded yes, and produced the book titled Red-Eared Slider Turtles. I was asked how much, to which I replied $8. In an exasperated, questioning manner, the gentleman literally yelled "$8 for a book?" and then promptly walked away.

Hatchling turtles, predominantly red-eared sliders are still produced in huge numbers on properties in the southern U.S. There are 80 turtle farms in Louisiana alone. The majority of the hatchlings are sold overseas, where the 4-inch law does not apply. However, individuals selling these baby turtles, or specimens removed from the wild, can easily be found in tourist hot spots and flea markets, selling to what are most likely uninformed, dime-store-equivalent shoppers of today. Responsible herpetoculturists notwithstanding, the FDA ban undoubtedly saves a staggering number of baby turtles from perishing as they did decades ago.