Crutchfield has captive bred and born over 200 species of reptiles from Nerodia to Sanzinia.

Unless one has been living under a rock for the past 50 years, Tom Crutchfield is a name that nearly every serious reptile enthusiast has at least a passing familiarity with. Born in Marianna, Florida in 1949, Tom began interacting with reptiles and amphibians at a young age. He would earn extra money by catching snakes, including rattlesnakes, for the Ross Allen Reptile Institute. Tom is one of the founding members of the hobby as we know it today, boasting many accomplishments. These achievements include breeding numerous species, including many for the first time, education, and field work such as participating in conservation studies with the San Salvador rock iguana, Cyclura rileyi. Having experienced his share of trials and tribulations over the years, Tom generously agreed to speak with us for this interview.

Reptile price list. Photo by Tom Crutchfield

FR: Hello Tom and thank you for taking time out of your day to engage in this interview. Much has been written about you but for those who may be unfamiliar could you tell us a little about your childhood and early interests in reptiles?

TC: Well, the earliest interest that I had with reptiles started with dinosaurs. I turned my first rock over in the yard at 6 years old and found that ringneck snake, that was the beginning of it all. I kept it in a jar and then released it. Then I learned how to find more. That was a time of great learning.

Tom with a Sri Lankan Palm viper Trimeresurus trigonocephala. Photo courtesy Tom CrutchfieldPhoto courtesy Tom Crutchfield

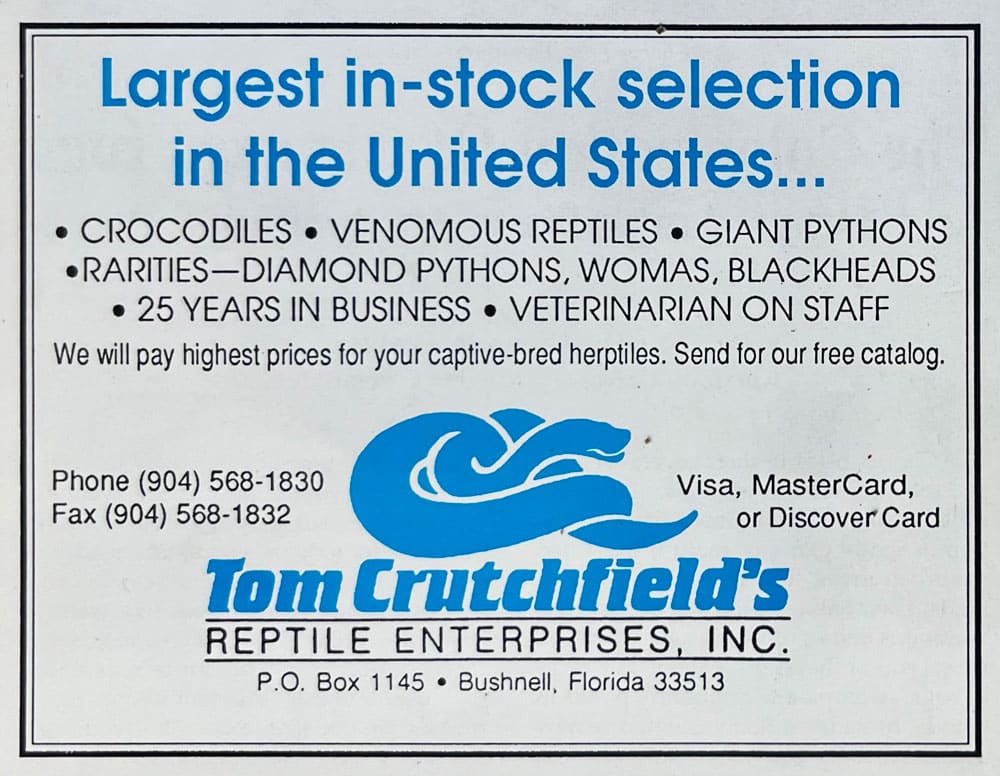

FR: You had a good start going into the beginning modern age of herpetoculture. Specifically, I am referring to the early to mid-80’s. During this period the hobby was becoming more popular however the husbandry magazines that arose closer to the end of the decade had yet to come about, the herp book boom had yet to begin, and of course we did not have the internet around back then. Were there any special challenges that you faced getting your name out there?

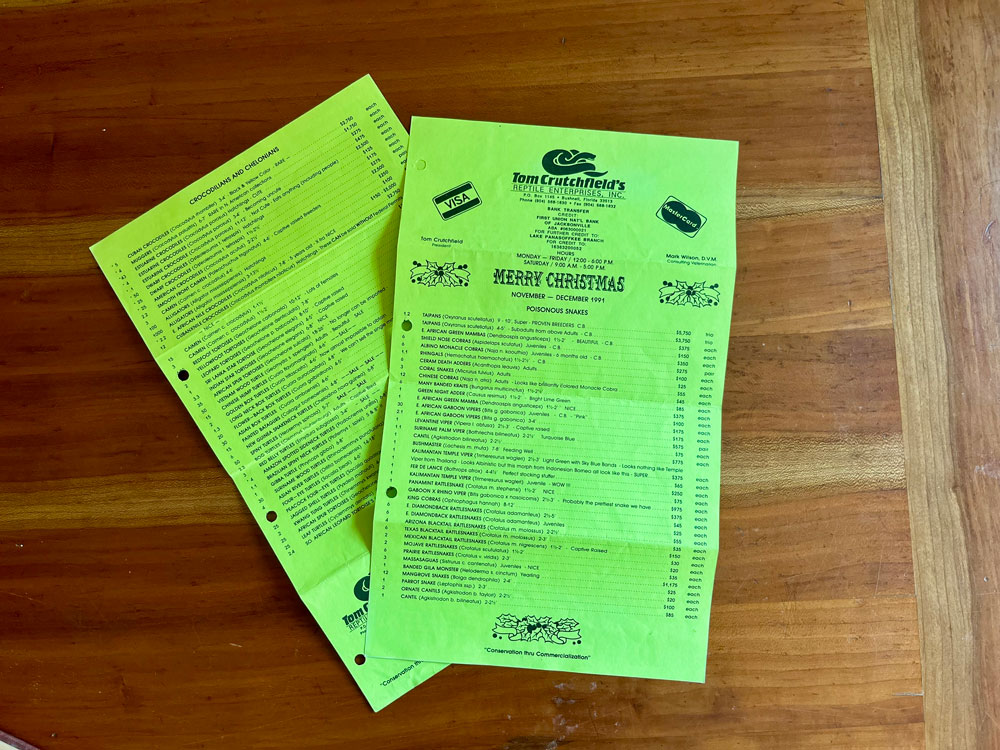

TC: I put a pricelist out during the 1980’s, called Herpetofauna Incorporated and it became a very, very large business over the next 10 or 15 years. There was also Herpetofauna International with Hank Molt, Western Zoological Supply with Jim Brockett and Barney Tomberlin, and all that sort of stuff. Basically, I was trying to make a living and learn how to keep as many reptiles as I could, because dealers get in more different kinds than any other place, zoos, or whatever. I wanted to see everything, so I put a pricelist out every month. Eventually that list grew to all the AZA Zoos in the US, little roadside zoos, and private people. At one point I think that we had 8,000 to 10,000 people on the mailing list. I say mailing list because we made lists out, thousands of them at a time. The greatest expense that I had was the pricelist. It was 32 cents a stamp for each list a month, every month.

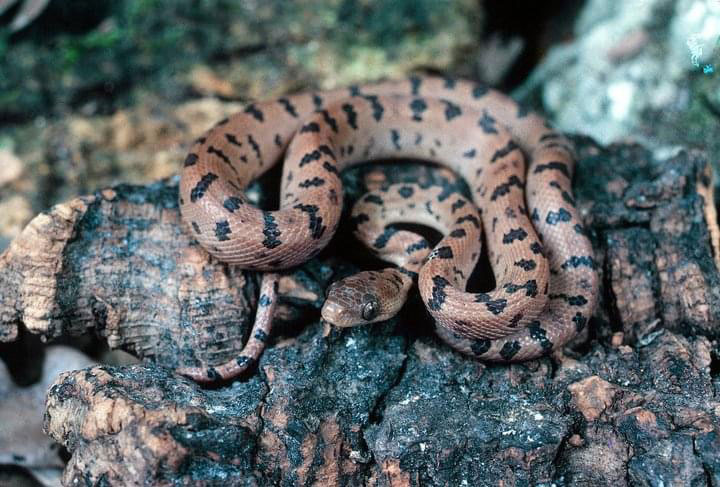

Bahamian Boa (Chilabothrus strigilatus). Photo courtesy Tom Crutchfield

FR: Do you think that the Bimini boa would be considered the gateway species that encouraged you to start collecting animals in other countries?

TC: Yes, it was because until recently the only thing that I could hope for would be going to the Everglades, or some unique part of Florida that I had not been to before. I had already been studying Caribbean boas at that time anyway and a lot of my friends were going to Bimini and catching them on the weekends. We collected in remote areas. On one trip we found an abandoned area where deserted boats were stored. We found a rolled-up sail stored in a building, and after pulling it down we discovered 24 boas. That was the most that we had ever found at one time.

FR: What are some of your most memorable experiences from these travels?

TC: Well one is the perception that collecting in the Caribbean was against the law, but it was not in that time period. I spent the most time in the Caribbean during my 20’s, until I was about 30. This would have been in the 1970’s when CITES was barely even heard of, and mostly not enforced. Everybody just caught whatever they wanted to bring back. They declared what they collected or just let the animals be discovered, because it just didn’t matter. No one really cared. I mean I know it sounds terrible but that is how it was.

Stacy Crutchfield with an albino cobra. Photo courtesy Tom Crutchfield

FR: During this time when you were importing large numbers of animals, at what point did you begin to focus more on establishing breeding populations?

TC: Well, what really slapped me in the face so hard were my first journeys around the world. I made three trips around the world, and this would have been the 1980’s. When you were as young as I was, you go to wet markets in Asia as well as other places. In Thailand we called it the Sunday Market, it’s the one in Chatuchak now. The live animal market was just unbelievable. Orangutans were for sale then. You could buy elephants, fish, any species you could possibly think of. Imagine a square mile of little tents, all private vendors, all selling legal and illegal stuff out front, and nobody cared. Some were critically endangered, and they were kept in horrible conditions until they died. It hit me in the face what was happening. I would look at the animals and think about this, especially during the Caribbean trips. You do realize that there are hardly any Bahamian taxa of Cyclura in captive hands in the US? None of them were really brought in much, other than a very few. These went to the old private part of zoos. We didn’t catch them on purpose because we were worried about other pressures, like the locals hunting them for food. The only species we took were mostly rhino iguanas, which were very common back in that time.

Stacy with Bill, a crocodile monitor. Photo courtesy Tom Crutchfield

FR: What are some of the species that many take for granted today that may not have been available if it were not for your efforts?

TC: I brought in 300 bearded dragons, Pogona vitticeps, early on. They mostly came from Switzerland. At least some of those survived to be bred. I wasn’t the only one that brought them in either. There were albino Burmese pythons. I had the first ones of those. Bob Clark got his from me that certainly was a big one involved in herpetoculture, particularly with morphs. Ringed pythons were brought in by Ed Celebucki and sold to me. There were about 20 to 24 snakes, and they served as the founder population for what we have in the US now. Ed and Hank Molt also brought Woma pythons in from Sydney.

Price list, Pre-Internet. Photo by Tom Crutchfield

FR: Tom you are a special breed of reptile keeper, even from the start. The average hobbyist does not keep venomous snakes until more experienced in the hobby, much less have crocodilian breeding ponds in the backyard. Approximately how many different species do you think that you have worked with over the years and how many have you bred?

TC: I have captive bred and born over 200 species of reptiles from Nerodia to Sanzinia! I know that I’ve bred 10 species of crocodilians, five species of Cyclura, both kinds of emerald tree boas, Corallus canius and Corallus batesii, the list goes on. There is Iguana iguana, Iguana delicatissima. I’ve bred hundreds of Cuban crocodiles; they were in my backyard too (Tom laughs). I’ve bred every species of Chilabothrus but three, two of which were only recently described. These include the Dominican red mountain boa (C. striatus), Jamaican Boa (C. subflavus), and Abaco Island Boa (C. exul).

FR: Tom, you have seen a lot of field-collected animals on dealer’s lists come and go over the years. Which species would you like to see hobbyists and breeders put more work into sustaining?

TC: When I choose reptiles to captive breed, I look at three factors. First, I must like the species I pick. Second, I choose to breed higher end reptiles as most buyers do not purchase on an impulse due to cost; and third, I choose a species in need for conservation purposes. Examples would be tree monitors, boas in the Chilabothrus genus, Cyclura, and so forth.

FR: I remember receiving your stock lists by mail back in the 80’s. In addition to an incredible selection in general, you offered high-end species found nowhere else, some going for six figures. Can you tell us a little about some of your exclusive clientele?

A Dominican red mountain Boa (Chilabothrus striatus). Photo courtesy Tom Crutchfield

TC: We sold a lot of expensive stuff back then; it was sort of our last form of public existence. Zoos were major buyers. We were the first to offer albino American alligators to herpetoculture. Alligator Adventure in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, got some of those. I also provided Alligator Adventure with a large male Sunda gharial, which I raised from a young juvenile in one of my crocodilian ponds.

FR: Have you ever been bitten by a venomous species or suffered an attack by a large lizard or crocodilian?

TC: I have been bitten three times by venomous snakes. I’ve never been bit handling a venomous snake, I had two bites through a bag, one bite was an Osage copperhead, which caused me a little damage to my finger, but I didn’t seek medical treatment. Then I got bit by a west African green mamba through a bag, but it was a dry bite. About 10 years ago I had a big SW speckled rattlesnake bite. It was too fast and barely hit me on the hand, but I didn’t have any envenomation. I’ve never had to take antivenin thank goodness. The worst I’ve ever been hurt by any reptile was a crocodile monitor bite about seven years ago. It damaged my finger, crippled my left index finger, permanently. It looks like I have a snake bite finger, it was just a warning bite, but I was in the hospital five days and had to have a blood transfusion.

Stacy with natives on a herping expedition. Photo courtesy Tom Crutchfield

FR: That does not sound like fun.

TC: (laughing) Yeah, it was the worst I’ve ever been bitten. I had a Gila monster bite me one day too, it was a terrible day that Gila monster bite, but nothing like that croc monitor bite (as he continues to laugh). After a lot of pain and swelling the Gila bite had no residual effects albeit the crocodile monitor bite was life changing and permanently crippled my left index finger.

FR: In addition to providing ample and humane space, what advice would you give those who are thinking about working with more unorthodox species, such as venomous animals, crocodilians, and large lizards?

TC: It goes back to this, only keep an animal if you can allow it to be the animal that it actually really is. If you can’t allow that, then perhaps you should choose a different species. To provide for a six-foot iguana is not the same as for an Anolis equestris.

FR: I absolutely love your philosophy of keeping fewer species and providing more space for what is being kept. In addition, it seems that you are influencing others to follow suit. What arguments would you give to those who may still feel that a minimal enclosure size is satisfactory?

TC: There is a difference in keeping an animal alive, or allowing it to thrive, a huge difference. Reptiles can sort of tolerate substandard conditions. A basic reptile cage can be viewed as a life support system. As an analogy a human being can be kept in a closet, as long as it is cleaned, and food and water are provided. Once the human grows up it may even reproduce if given a mate. Obviously, a situation like this would have profound psychological implications on that human, and it is the same with reptiles. One thing reptile people don’t take into account or really understand is the amount of intelligence and mental holdings that these animals really have.

The same question that I always ask the people that criticize me for my stance on keeping giant snakes in Vision cages and the like is, just give me one reason, why keeping giant snakes in small cages benefits the kept, and not the keeper? Give me one reason and I won’t criticize anymore. Every single reason that they can give you for keeping them in smaller cages is that it can keep them alive and fed, but the animal doesn’t understand this. I also want to point out that I am not targeting any particular individual with these statements, if someone feels targeted then maybe they should reexamine their husbandry methods. I have kept snakes in large wire cages outside for years, even back in the 1980s. Over the last 15 years I have even increased the size of these cages even more. People would ask, don’t they rub their noses? They do not because they have habitats inside the cage with temperature gradients, live plants, and all kinds of stuff. I want to increase the size of their habitats so that they can be the creatures that they really are. Most big pythons like to climb, and many lizards like to dig. When housed in this manner there is a very noticeable difference in how they respond to their keeper. I had crocodiles in my front yard for years. My false gharials are huge and had like a fourth of an acre enclosure in the front, but I would never keep something like that if I had not had the ability to provide for it in this manner.

FR: It is no secret that many keepers tend to anthropomorphize their animals. While this is certainly part of human nature, many people will argue that, with certain exceptions, most animals kept by the average hobbyist may learn to associate human presence with food but otherwise seem indifferent to their keepers. You have pushed past this base interaction however and have formed real bonds with so many of your animals. Could you tell us about some of these relationships?

TC: Well, you know to be perfectly honest with you in our later years here nothing has ever tried to bite anyone here, except for the cobras on the venom line, even the other venomous animals like the Gilas. The main memory is about the big Mangshan viper that I imported 15 years ago and subsequently raised. She was gigantic and that was the only venomous snake that I have ever totally trusted not to bite. If I were to go into her cage, she would uncoil and crawl over. I have pictures of her coiled up tight on the bottom, with that big head on top, with my hand laying on top of her and her doing absolutely nothing. If I waited a minute, she would climb up on my shoulders. I’ve never seen anything like it before or since. I’ve never trusted any venomous reptile before like that. I had her as a baby. I was careful never to scare her, as she grew, she became very non-afraid of us, and very forgiving. One time she did a feeding strike. I saw the big head coming fast toward my hand but all of a sudden, the big head stopped, and she put her head down on top of my hand. She aborted a full strike, full Monty, right before contact, when she realized what the target was. Kristine Bialecki, who is well known on Facebook, was here and saw that. She taught me so much more than I would ever know by being so forgiving. I’m not an academic, my classroom has always been the living reptiles.

FR: Tom, you have done a fantastic job with that.

TC: Thank you, sir.

FR: Could you explain the concept of Umwelt?

TC: Umwelt means reality is viewed in different ways and how the animal adapts. Umwelt is a German ethological word that basically says that every organism reacts with reality in a different way. For instance, the world of a catfish, versus the world of an iguana, versus the world of a monkey, and so it goes. Unless one can understand the umwelt of the animal, the behaviors, where they come from, where they originate from, it’s very hard to understand the ethology, basically what not to do. Some people seem born that way, Stacy is one of those people, and she is an amazing person.

FR: Funny that you mention that because I want to ask about her in the next question.

FR: Tom, tell us about your wife Stacy. I really wish that this question could begin on a more upbeat note. Throughout the course of this interview, she has suffered a life-threatening bout with bacterial and fungal pneumonia. She was intubated while hospitalized, then transferred to a rehabilitation facility, and even after returning home her condition is not improving.

During one of our telephone conversations, you shared that she is still not fully ambulatory. To make matters worse, the extensive IV antibiotic regimen that she received while in the hospital has now resulted in Stage 3 liver failure. You went on to say that there is an upcoming appointment at the Clevland Clinic in Ft. Lauderdale to determine the options, especially if she transitions to Stage 4 liver failure. Let me say that I am so sorry and can only imagine what you are going through. As a nurse I know well how traumatic these situations are for family members. I speak for the entire herp community when I say that our thoughts and wishes are with both of you. How long have you two been together? She obviously shares your passion for animals. Does she have any favorite species?

TC: Well, this past June (2025) will be 10 years, and we have been married six years, and we have been a couple for eight years, a long time. She has many favorites but one is Hemingway, one of our rock iguanas. We have them loose in the side yards. They don’t even have cages, they live there. We have five big Cyclura that live in partitions, mainly chain-link fences, which are not particularly difficult for them to get over (Tom laughs), but they don’t, they understand their territory. Those are some of her favorites. Bill, the big crocodile monitor, Stacy has a remarkable relationship with him, and honestly, she taught me a lot of the croc monitor ethology herself.

FR: Tom, your notoriety as a smuggler decades ago is well documented in various books as well as on television. If this were to happen today, in the age of the internet, I suspect that the knee jerk reaction of the faceless hordes online would be coming after you with digital torches and pitchforks. This said, you enjoy a huge respect in our community, not only in the US but across the globe. People go out of their way to shake your hand and have pictures taken with you at shows. What do you think accounts for this?

TC: It was a different time then. I have just never claimed to be anything I’m not. I’ve never lied about anything I’ve ever done, it’s factual, a part of history that you just can’t deny. Did you know that zoos participated in rattlesnake roundups back then? Zoos were more concerned about getting animals for exhibits than where they came from. Once I received some water monitors that actually turned out to be Gray’s Monitors (Varanus olivaceus). Several zoos bought them quickly. Some of the stuff I’m sorry I did, and some of the stuff I’m sorry that I didn’t do more of. It was never completely about money either.

FR: Tom you are a key character in Eric Goode’s upcoming HBO docuseries about the herp community. Could you tell us about this experience?

TC: He started filming in 2011, and then one day Mark McCarthy shows up in my yard with a snow leopard, and Tiger King was born. I knew Eric before, when he had the night club, Area, in New York City. He had a lot of movie stars attend. He was a Hotelier too, and he had reptile exhibits in his nightclub. I provided reptiles for some of those exhibits. I knew that he was a big turtle and tortoise guy, and I applaud what he has done conservation-wise around the world. I did not, however, realize to what great extent he was taking. He took a lot of pictures, but I did not expect any movie like that, because that’s not what he told me it was about. He had other people that he filmed also that you will recognize. After Tiger King, he comes back and wants to video tape me again. I don’t know if I want to do it or not. If I had not filmed for five years before Tiger King came out, I never would have done it. Since he had already filmed me, however, I decided to explain and do the best I could.

FR: Tiger King and Chimp Crazy both featured some unique characters which did not reflect well on big cat and primate keepers. Did you ever get the sense that Eric may paint the reptile industry in a bad light?

TC: No, not at the beginning. It’s a mixture of excitement and dread post Tiger King. Eric and I have been friends for a long time however so I will give him the benefit of the doubt.

FR: Tom thank you so much for agreeing to participate in this interview. We wish Stacey a speedy recovery and hope that your transition to your new place is as seamless as possible. Are there any parting words that you would like to share with our readers?

TC: It’s bittersweet, but it’s the last of my big reptile farms down in Homestead. I loved the way I lived for years and years and years, until I became an old man, literally, me living in the place I lived if that makes sense. Anyway, when life serves you lemons, you turn it into lemonade.

Foster Reves is a SW Virginia based Registered Nurse and freelance writer. Foster lives with his two amazing kids and too many other animals to list.