Thermal burns in reptiles are one of the most common injuries seen by herp veterinarians.The exact reason why reptiles seem so prone to burns is not u

Thermal burns in reptiles are one of the most common injuries seen by herp veterinarians.The exact reason why reptiles seem so prone to burns is not understood, but something about their behavior makes them more susceptible to this type of injury than any other captive animal.

Because reptiles do everything slowly, it is not uncommon for an animal to get burned, but not actually show signs of the injury for several days. This is especially true for minor, or first-degree burns. This is significant, because burns, even apparently mild injuries, can have severe consequences if not treated properly.

Thermodynamics

Reptile keepers are all familiar with the importance of providing proper temperatures to the cage environment, and we have seen the evolution of heating devices from the original “hot rocks” to the more advanced, thermostatically controlled environmental devices available today.

We have learned that not only must captive reptiles have supplemental heat, but that it must be provided in the proper fashion. For instance, a 15-foot-long python would not fare well with a single, 12-inch hot rock. Likewise, a nocturnal lizard would suffer if its cage were heated with a bright heat lamp. Providing improper heat sources are a common cause of burns.

douglas mader

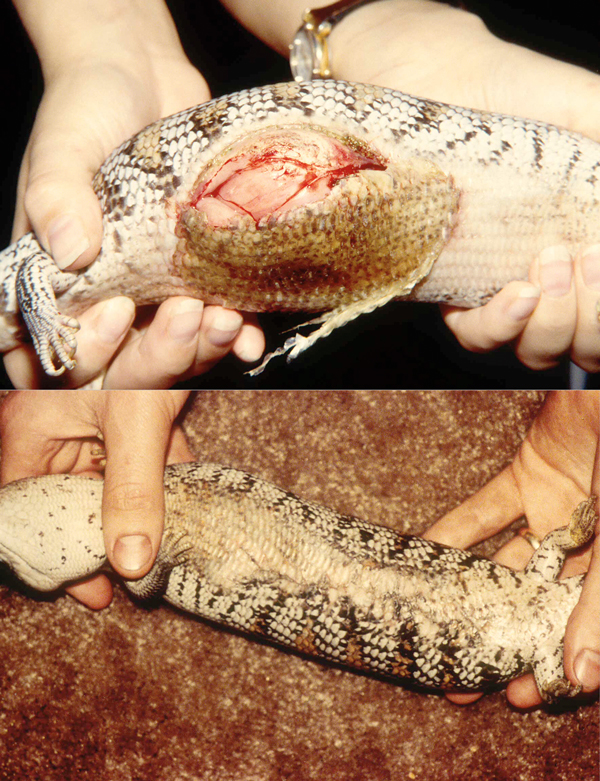

This skink developed a third-degree burn on its belly after falling asleep on a “hot rock.” It took surgery and three months’ worth of treatments, but it finally healed, though with some severe scars.

In order for an object to become warm, or “heat up,” there must be a transfer of heat from some outside source to the object that is being heated. Heat always moves from a warmer area to a cooler area, and there are three ways to warm an object: conduction, convection and radiant heat.

Conduction is the transfer of heat within an object (such as down a long, metal pole) or between two objects that are touching each other. A herpetological analogy here would be the use of a hot rock. If a reptile crawls onto a hot rock, the heat from the rock will transfer, via conduction, to the lizard due to direct contact.

Convection involves the transfer of heat via the movement of either gasses (such as air) or liquids (such as water). Consider the warm air over a desert. As the surface of the desert heats up from the sun, it warms the air that touches it (this is conduction). Warm air may then blow across a basking reptile, heating the animal via convection.

Radiant heat transfer involves the flow of thermal energy by electromagnetic waves. In contrast to conductive heating, in which objects must be touching, or convective heating, where matter (gas or water) must touch the object to be heated, radiant heat does not have to have any matter involved, as no actual touching is needed for heat transfer. The classic example here is a fast-food hamburger under a red heat lamp. The obvious herp example would be a lizard basking in the sunlight. It is soaking up the electromagnetic radiation produced by the sun’s rays. In captivity, this source of electromagnetic radiation is replaced by any number of artificial means, usually a heat lamp or a ceramic bulb.

There are several other variables that play important roles in heat transfer and warming. Moist air, or high humidity, tends to hold heat much better than dry air. When figuring temperatures and thermal gradients, careful attention should be paid to humidity. A hot, humid cage will be much more stifling than a hot dry cage.

Of the three types of heat transfer, the two that cause the most injuries are radiant heat and conductive heat. I have seen hundreds of burns caused by hot rocks. These crude heating devices have variable heat output, often unevenly distributed over the surface of the rock, and can reach temperatures that will sear the flesh off any animal that rests on it.

Humans have a withdrawal reflex. When we touch something hot, without any cognizant thought, we automatically and immediately withdraw our hand. Reptiles, however, apparently do not possess this same reflex, and it is not uncommon for them to fall asleep on a hot surface and literally burn their skin off with no reaction.

Types of Burns

The extent and severity of a burn is related to several factors. Obviously, the temperature of the heat source plays a significant role. Duration of contact also affects the severity of a burn. Again, touching a stove burner set on “warm” only briefly may result in a minor burn, whereas holding one’s hand on the same burner for several minutes may result in much more severe tissue damage. This is, perhaps, why we see such intense damage in reptiles that have fallen asleep on what seems like only a mildly hot heating element, such as a hot rock.

Lastly, the heat conductance characteristics of the material being touched also plays a role in the severity of a burn. For instance, touching a hot piece of metal would cause a more severe burn than touching a piece of wood at the same temperature.

In older terminology, burns used to be classified as first, second or third degree, depending on the severity of the damage. In more recent classification, the terms “partial thickness” and “full thickness” burns, are more commonly used (“thickness” refers to the outer layer of skin).

Though they are painful, first-degree burns are superficial, partial thickness injuries that only involve the epidermis (outer skin). In reptiles, you rarely see blisters, although they may occur, and occasionally, you may see singing of the scales, depending on the type of exposure.

Second-degree burns are deeper, partial-thickness injuries, usually with full destruction of the epidermis and variable damage to the underlying dermis (the inner, deep layer). In reptiles, blistering and oozing of serum from the burn site are seen with second-degree burns. There is also extensive bruising and discoloration of the tissue. These injuries lead to the formation of a scab-like covering over the burn.

Third-degree burns destroy the entire thickness of the skin. The burn is actually painless, because all the pain-sensing nerves are destroyed, and the tissue takes on either a whitish or charcoal-black appearance. Third-degree burns are four times as serious as second-degree burns of similar size.

Burn Treatment

Reptiles are amazing animals, and they have a penchant for healing that’s far greater than any mammal. Pain control and infection prevention using appropriate topical and systemic antibiotics, as well as supportive care with fluids and supplemental feeding are all necessary when treating a reptile that has suffered a burn injury.

The reason why reptiles are so prone to burn injuries remains a mystery, but understanding the causes of burns and the mechanics of tissue injury will help prevent such occurrences, and, in the unfortunate event that they do happen, better manage their care.

The most important take-home message here is that when dealing with burns in reptile patients, be diligent, be clean, and, above all, be patient!

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.