Research from the nation’s top snake inclusion body disease expert.

Managing a Snake Collection

I have not seen a snake collection where only a single case of IBD has been diagnosed. Typically, where there is one, there are others. So what should one do in such situations? Based on my experiences, snakekeepers have approached this problem in different ways. In extreme cases some people have depopulated their entire collection of exposed snakes susceptible to infection, or where IBD has been diagnosed in a large number that either share the same room or have been in contact with one another. Others appear to be in denial despite evidence that IBD exists in their collection and have decided to go along with business as usual. I have seen it all.

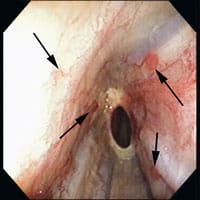

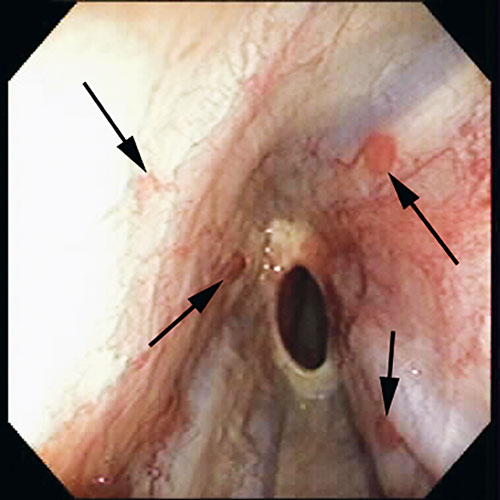

Photo by Elliott Jacobson

A flexible endoscope passed down through a boa constrictor's esophagus reveals its esophageal tonsils.

Such a range of responses has been seen in all sorts of animal-breeding operations. What has made a difference in controlling and managing infection outbreaks in domestic animals is twofold. First is the ability to develop very sensitive and specific diagnostic tests. The “sensitivity” of a diagnostic test is the ability of a test to identify all positive animals in a population that are infected with a specific pathogen, and the “specificity” of a diagnostic test is the ability of a test to identify an animal as negative in a population 100 percent pathogen-free. Second is the development of vaccines that can protect animals from infection and disease.

No cure exists for IBD, and no vaccines are available for protection against the disease’s causative agent. Vaccine production is extremely costly, and odds that the money needed for their development will become available are extremely low.

Currently IBD diagnosis is based upon identifying inclusions in cells from tissue sections or blood films. The sensitivity and specificity of these examinations performed under a light microscope is unknown, but it is more than likely not as good as it should be. Although many snakes with the disease have numerous inclusions in multiple tissues, others have few that may be confined to one area of the brain. Additionally, inclusions resembling those seen in IBD have been seen in snakes having some other disease process, and distinguishing them from inclusions seen in IBD can be difficult. So determining which snakes are infected and which are free of IBD in a snake room where an IBD-infected snake has been found is not that easy.

Yet some things can be done. Biopsies and blood films can be obtained from exposed animals to screen for inclusions. If it is financially impossible to obtain samples from all animals, then select a subset for evaluation. Snakes showing signs of IBD should be immediately removed from the main collection and moved into a separate room, or submitted for a tissue evaluation under a microscope and/or necropsy. Cages of ill or dead animals should be disinfected with bleach and left out in the sun for a few days to dry. Bleach is the best overall disinfectant. Although it will not kill every pathogen known to snakes and other reptiles, it is highly recommended.

I have been asked many times whether the agent causing IBD can be transmitted to neonates of either live-bearing or egg-laying snakes. We have very little information to determine whether this can happen. I have received anecdotal reports that recently hatched ball pythons were diagnosed with IBD, but I could not obtain the microscopic slides on those cases to substantiate the finding. I once received a series of neonate boa constrictors that had an IBD-positive mother, but inclusions of the disease were not found in those neonates.

IBD-Affected Snakes

• Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivitattus)

• boa constrictors (Boa constrictor)

• green anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

• Haitian boa (Epicrates striatus)

• Indian python (Python m. molurus)

• reticulated python (Python reticulatus)

• ball python (Python regius)

• Australian carpet and diamond pythons (Morelia spilota ssp.)

The problem is that we do not have the needed molecular-screening tools with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity to properly screen these animals. The conservative viewpoint is to assume that the agent can be transmitted to offspring, so babies from known IBD-positive females should not be kept, sold or given away.

Inclusion Body Disease Present Research and Future Needs

Recent studies have documented that the inclusions in IBD consist of a unique protein with a mass of 68 kilodaltons. Some of our current work centers on better understanding the composition of this protein and developing a test to identify its presence. If there is any hope or desire for IBD to be managed in breeding operations of these snakes for the pet trade, the need for such molecular-based tests is clear.

The problem we have faced with the research done on IBD is that research dollars needed to do the work has been extremely limited. Although the Mid-Atlantic Reptile Show, the National Reptile Breeders’ Expo and a number of private individuals have made contributions to our work, the total number of dollars received has been fairly small in order to do the necessary work.

I have submitted several research proposals to various animal foundations for the funding needed in order to develop the necessary molecular-based diagnostic tests, but so far, the funding hasn’t come through. Still, a new graduate student is in place in my laboratory to do this work, and one way or another, we will secure the money needed to get this done (a two- to three-year project). At least I am hopeful that such a test or tests will be available by the time I am just about ready to retire from my current faculty line at the University of Florida. I could not have worked at a better university to pursue my interest in reptile medicine and disease.

Concluding Remarks on IBD

Inclusion body disease is one of the few worldwide diseases of captive snakes. It has been identified in captive pythons in Australia, and there is concern that it will become established in native wild populations. There is also concern elsewhere in the world where snakes are being bred for release to the wild.

Snakes make up approximately 19 percent of all reptiles kept as pets. Of these, boa constrictors and pythons — especially ball pythons — are bred in large numbers for the pet trade. Because many IBD-affected boid snakes may not show outward signs of the disease, infected snakes considered healthy have been sold. We do not know what percentage of snakes with IBD will develop clinical symptoms and how many will remain clinically healthy. It is possible that latent infections can persist for long periods.

Thus it is a snake breeder’s obligation to make sure that quality and healthy animals are being sold. Part of this is making a significant investment in important research efforts to solve the mysteries of this insidious disease and others like it. Bird breeders have done this, and there is no reason it cannot be done for reptiles. Ensuring healthy and disease-free animals should be the primary responsibility for all who keep and breed them.