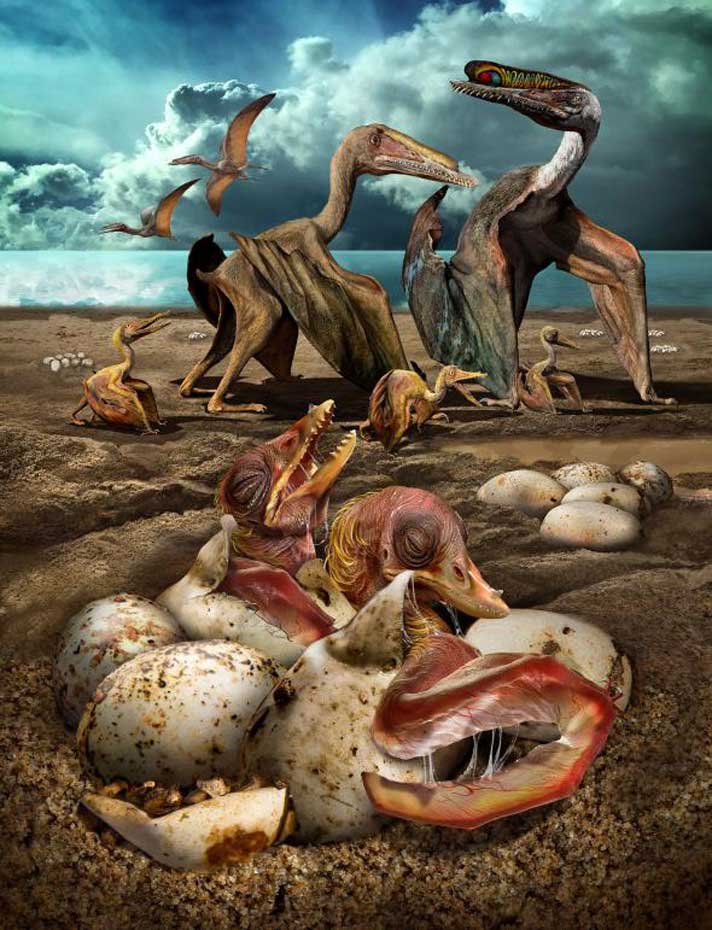

More than 200 eggs were found, including 16 that have detailed embryos of Hamipterus tianshanensis.

Paleontologists have discovered a nest of ancient reptile eggs laid by pterosaurs, winged reptiles that flew alongside dinosaurs during the Mesozoic era. What is unique about the discovery of the 215-300 eggs is that they are very well preserved, with some of the eggs featuring very highly detailed pterosaur embryos, in what may be the most detailed pterosaur eggs found yet.

ILLUSTRATION BY ZHAO CHUANG

More than 200 eggs were found, including 16 that have detailed embryos of Hamipterus tianshanensis.

The eggs were discovered in China by Chinese Academy of Sciences paleontologist Xiaolin Wang. So far, 16 of the eggs have detailed embryos of Hamipterus tianshanensis, a species that lived more than 100 million years ago in northwest China, according to National Geographic. The Pterosaurs is said to have had a wingspan of 10 feet and most likely fed on fish.

“The site is in the Gobi desert, and there are strong winds, a lot of sand, with few plants and animals,” study coauthor Shunxing Jiang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences told National Geographic. “However, when Hamipterus lived, the environment [was] much better—we call it Pterosaur Eden.”

Want To Learn More?

43 Dinosaur Eggs Unearthed in Heyuan China

Pterosaurs fed in the area and also laid their eggs in the so-called Pterosaur Eden. Scientists say the eggs became fossilized in lake sediment that they claim was disrupted by fast-moving water. The researchers think the nesting site was flooded several times over, which leads the researchers to believe thje nesting site was used repeatedly over time. In addition, the sheer volume of eggs discovered leads Wang and his colleagues to believe that the pterosaur's bred in large colonies like certain bird species.

Sediment infiltrated eggs that had split open during these water events helped to preserve the the oblong shape of the eggs as well as the skeletons of the developing embryos. One of the bones found at the site is believed to belong to a pterosaur hatchling, which is a key to the development cycle of the ancient reptile.

“We could look at the bones and see what features characterize an embryo, a hatchling, and a young individual when he’s matured,” coauthor Juliana Sayão, a bone-structure expert at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, told National Geographic. “This is a one-of-a-kind record for pterosaurs—for the first time, we have the whole spectrum.”

According to the paleontologists, the shells of Hamipterus tianshanensis resemble those of living turtle’s leathery eggs, which implies that the pterosaur buried its eggs to keep them safe. How or where is the big unknown, which the researchers may hope to solve by finding an undisturbed nest.

“What’s on my wish list?” coauthor Alexander Kellner, a paleontologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro asked National Geographic. “Number one: to find more embryos. Number two: I wish we would find eggs in situ—that means ‘not moved.’ We would learn a lot from that.”