Blood drawn from mountain yellow-legged frogs confirms cause of death.

The chytrid fungal infection responsible for devastating frog populations worldwide kills wild frogs via dehydration, just like in a laboratory setting, according to a study by San Francisco State University and University of California, Berkeley researchers. The fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) wreaks havoc on a frog’s fluid and electrolyte balance by thickening an infected frog’s skin, depleting the amphibian’s sodium and potassium levels, which causes cardiac arrest and death.

Photo credit: © 2012 Voyles et al

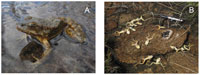

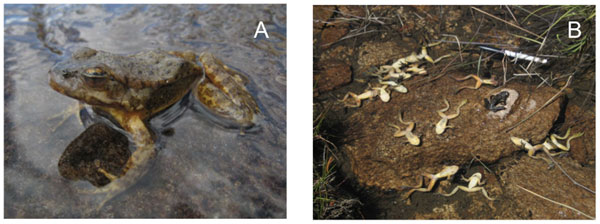

A) A frog showing clinical signs of severe chytridiomycosis including abnormal posture. B) Dead frogs following a chytridiomycosis outbreak in Milestone Basin in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California.

In 2004, Vance Vredenburg, an assistant professor of biology at San Francisco State, drew blood from wild mountain yellow-legged frogs as the chytrid fungus spread through the Sierra Nevada range where the mountain yellow legged frogs (Rana muscosa) reside. Vredenburg and other researchers determined that death of frogs from the chytrid fungus in a laboratory setting was largely the same as how wild frogs infected with the chytrid fungus died. “The mode of death discovered in the lab seems to be what’s actually happening in the field,” he said in a statement released by San Francisco State University, “and it’s that understanding that is key to doing something about it in the future.”

According to the study, the fungus attacks a frog’s skin, causing the skin to become up to 40 times thicker than normal. The skin, which is normally permeable, is unable to absorb water and electrolytes that frogs rely on to survive.

“It’s really rare to be able to study physiology in the wild like this, at the exact moment of a disease outbreak,” said University of California, Berkeley ecologist Jamie Voyles, the lead author of the paper.

The study cannot be duplicated because mountain yellow legged frogs, now on the Endangered Species List, in the Sierra Nevada basins have declined 95 percent since the outbreak was first recorded there in 2004. But the study may lead to new therapies for individual frogs, such as treating those infected with the fungus with electrolyte supplementation during the advanced stages of the fungal disease. Other ways of treating frogs in the lab include the use of antifungal therapies and injecting frogs with probiotic bacteria that kills the fungus. “The disease is not very hard to treat in the lab with antifungals. We know we can treat animals there,” Vredenburg said. “But in nature, the disease is still a moving target.”

The mountain yellow-legged frog, the subject of this study, is around three inches in length and lives in high elevation lakes, ponds, streams, and pools of water in Southern California. It hibernates in the winter months. The frog lays eggs in the spring and the tadpoles arrive approximately two months later and remain as tadpoles throughout the summer, winter, and following spring. They then start to metamorphose into frogs the following summer and fall. As adults, they can live 10-15 years. It is estimated that there are fewer than 200 mountain yellow-legged frog’s left in the wild.

The full study can be read here.