How to interpret the weather forecast to enhance your herping adventures.

There is more to field herping than merely encountering reptiles and amphibians. Not only are there a multitude of other fauna, flora and geologic features to be seen, dynamic climatic conditions can play a significant role in our overall enjoyment — both in aesthetic terms and in altering our herping success. In this article, I will discuss general weather trends, resources available to aid in planning an outing, basic weather prediction techniques, and equipment and methods for data collection in the field.

Photo by Chris McMartin

Some herpers chase storm systems, but in different directions (toward or away), depending on their target species’ moisture preferences. This summer storm is developing the classic “anvil” typical of large storm cells and has the potential to produce heavy rainfall and even hail.

Weather Trends to Look For

General trends in weather patterns typically have astronomic origins. Everyone knows summers are warmer than winters, with lengthening days and gradually increasing temperatures in the spring followed by a reversal of this pattern in the fall. This is due primarily to the tilt of the earth’s axis relative to the sun. On a shorter time scale, while not necessarily weather-related, the moon phase is also often correlated with variations in outdoor herp activity.

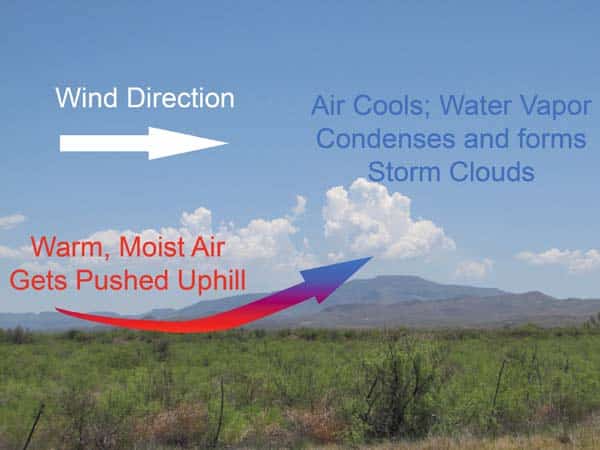

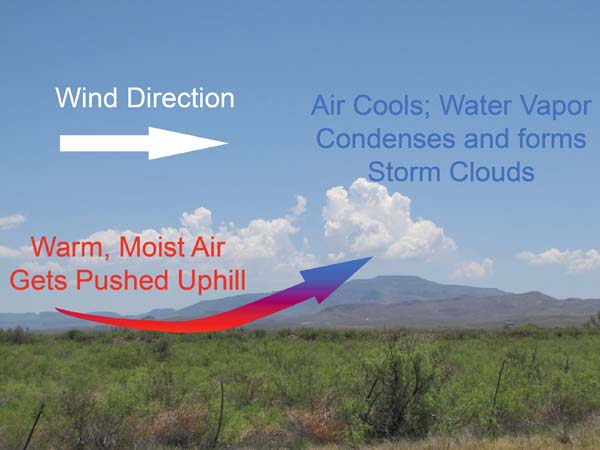

Photo by Chris McMartin

Cumulus clouds developing into thunderstorms via orographic lifting over the Davis Mountains in West Texas.

The atmosphere broadly behaves along the same trend as the seasons. But even in the summer, cold fronts can still sweep across a continent, though “cold front” is more descriptive of the origins and characteristics of the front than potential drops in temperature.

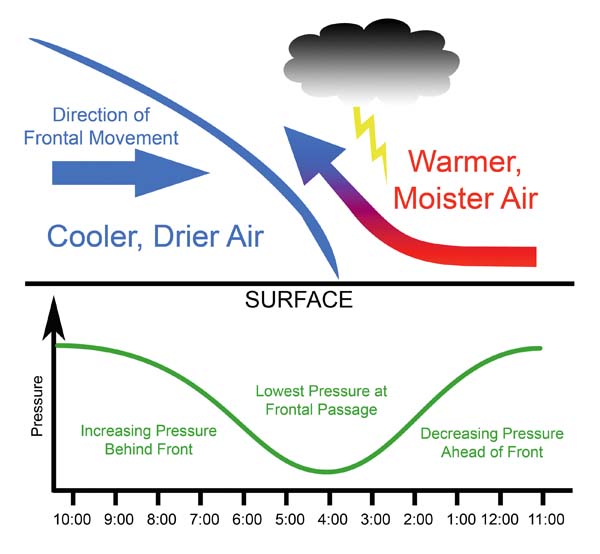

Cold fronts are useful to the herper for two reasons: pressure variation and thunderstorm potential. As a cold front approaches, barometric pressure decreases, reaching its lowest measurement at frontal passage. This is helpful to remember when pursuing species sensitive to pressure changes. Additionally, the higher-pressure air mass behind the cold front lifts the warmer, less-dense air mass ahead of the front higher into the atmosphere. If this air mass is sufficiently moist, showers and thunderstorms will develop along the frontal boundary. Generally speaking, cold fronts in the United States move from northwest to southeast. Furthermore, wind ahead of these fronts blows from the southwest, which is why storms associated with cold fronts typically track from southwest to northeast. The wind behind a cold front blows from the northwest (perpendicular to the frontal boundary and in the same direction the front is moving).

Following a cold front, air pressure is typically high. This usually signifies what most people call “good weather”— sunny, clear skies. These conditions are beneficial if your target species include diurnal reptiles, but not as helpful if you’re after rainfall-loving amphibians. Low pressure is associated with less atmospheric stability, bringing with it showers and storms, and ideally, the herps which enjoy such conditions.

Areas of low pressure are often responsible for helping to bring moisture from the Gulf of Mexico into the central United States. This is due to the circulation patterns associated with low-pressure systems. In the Northern Hemisphere, high-pressure systems experience a clockwise flow, whereas low-pressure systems result in counterclockwise flow (note: in the Southern Hemisphere, it’s the opposite). In other words, if you see an “H” on a weather map, wind will generally blow clockwise around it and counterclockwise around an “L.”

Some herpers swear that the direction and speed of the wind plays a significant role in predicting target species activity. For general wind-trend information not associated with high- or low-pressure systems, examine the isobars on a weather map. Isobars are lines connecting areas of equal atmospheric pressure. Thanks to the Coriolis effect, wind blows roughly parallel to the isobars. Where the isobars are close together, it will be windier than where they are widely spaced, much like closely spaced contour lines on a topographic map indicate steeper areas.

Gina Cioli/I-5 Studio

The Nuevo Leon kingsnake is a montane species that can be found in Sierra Madre. When herping in such an area, it is important to prepare in advance. The temperature is usually hot, but changes can be extreme and you don’t want to be caught unprepared.

The above-mentioned descriptions of weather phenomena are generic in nature. Research seasonal patterns for planning your specific herping location. Time of year plays the largest role in general weather trends, but local topography, ocean currents and other factors influence regional patterns. Examples of local/regional weather patterns include the Chinook winds in southern California, the monsoons in Arizona, and of course hurricane season in the Gulf and Atlantic states.

Local topography can affect weather through orographic lifting. In layman’s terms, wind blows a warm, moist air mass up the side of a mountain. As the air mass rises, it cools; the moisture in the air condenses to form clouds. With sufficient moisture, rain showers and thunderstorms can develop. Depending on the height of the land features, the terrain can merely serve as a “jump start” for thunderstorms, which continue to develop as they move past the mountains, or the mountains can “trap” the precipitation on the upwind side, resulting in regions of cloud forest, and a “rain-shadow” effect downwind (as seen in the Great Plains region of the U.S. — the Rocky Mountains trap significant moisture, and the effect can be seen in the west-to-east progression of vegetation in short-, medium- and tall-grass prairie).

This information is beneficial to the herper because it can narrow down areas in which to go herping. Study range maps and cross-reference rainfall maps. Gaps in distribution data for a species may be filled in by studying where rainfall conditions permit suitable vegetation to grow, and where annual rainfall is similar to areas where the species has been found previously.

Your area may receive rainfall in the spring, but your destination may not; it may not be hot and dry in the Big Bend of Texas in June (that is often when the region experiences its heaviest rainfall!). Research your target location and talk to people who live there to gain insight on regional weather patterns.

Resources

Weather information comes in two categories: real-time observations and historical data. Both can be useful to the field herper. In addition to current temperature, humidity, wind direction and speed, and pressure, many enthusiasts find radar coverage helpful.

Photo by Chris McMartin

A “cross-section” of an advancing cold front. The colder, drier, denser air mass behind the front pushes warmer, moister air higher into the atmosphere, where it cools and tends to form lines of thunderstorms. The lower half of the diagram shows the corresponding change in barometric pressure as the front passes.

Radar picks up “echoes” reflecting off objects. For weather radar, this is usually some form of precipitation. Radar does not generally show cloud cover, only actual precipitation, even if it’s not reaching the ground. Many weather websites can display “radar loops” from the preceding 30 to 60 minutes to help predict storm direction and speed. While radar information may display differently from one website to the next, all the raw data comes from the same radar stations owned and operated by the National Weather Service.

Current rainfall information is helpful in the search for some species (e.g., amphibians stimulated by precipitation), but for other herps (many reptiles) it is more important to know amounts of recent rainfall. Two useful sites are the National Weather Service’s Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (water.weather.gov/precip) and the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (cocorahs.org).

The NWS site is interactive, enabling a variety of views based on region and time frame of interest. Users can also overlay county lines, highways and rivers to better pinpoint exact rainfall locations and amounts. You can also display the difference between current/recent precipitation and historical amounts. This helps determine whether an area is experiencing unusually dry conditions despite recent rainfall, for example.

Photo by Chris McMartin

A young gopher snake encountered on a rainy night of road cruising in west Texas in October 2006. Generally speaking, rainy nights in this region produce more amphibians than reptiles, but recording climatic conditions with each find may reveal surprising natural history information.

The CoCoRaHS site is less intuitive, but it can be more useful. CoCoRaHS is updated every 10 minutes, but it relies on a network of volunteers to submit data. Some parts of the United States have a higher density of participants than others, resulting in more accuracy than the NWS site, which uses mathematical modeling to fill gaps in coverage.

Many weather-related websites provide moon phase and sun/moon rise and set information for the current date. For longer periods of time, various websites will even calculate local sun/moon rise and set tables for an entire month. This comes in handy when planning to take time off work around the new moon for herping travel!

For those already on the road, applications for mobile devices are an exciting new development. Instead of monitoring the Weather Channel on TV in a motel room before heading out for a night of road cruising, you can view radar storm loops and other pertinent weather information from anywhere your mobile device can maintain Internet connectivity.

Equipment

Weather observations can increase our understanding of exactly what conditions a given species may prefer, so carry equipment for measuring these conditions. The most basic is a thermometer for measuring air temperature. A “temp gun” is also helpful to determine surface temperatures, such as rock/soil, road surface or in a burrow. The truly meticulous can purchase a combination device with a built-in hygrometer, anemometer and barometer. All of these devices are relatively small, lightweight and easily carried in a pocket or day pack.

Photo by Chris McMartin

Collecting weather data in the field, in this case, at "Snake Road" in Illinois. The instrument shown here can display temperautre, humidity, wind direction and speed, and barometric pressure. Children often enjoy being included in the data collection process, and it may spur further interest in more advanced research later in life.

It is also useful to know how to read atmospheric conditions while afield in order to forecast general trends in the local weather. One method is to turn so the wind is at your back. Low pressure will generally be to your left (recall the previous pressure systems discussion). In the Southern Hemisphere, the low pressure will be to your right. Knowing where low pressure exists may help determine where precipitation is likely to develop.

Clouds may provide similar clues. Cumuliform clouds (the “cotton ball,” puffy clouds) are sometimes called fair-weather clouds; however, they indicate atmospheric instability. They can develop into their big, mean brother, the cumulonimbus — more commonly known as thunderstorms. Stratiform clouds, the smooth, layered types, mean greater atmospheric stability and less likelihood of violent precipitation such as thunderstorms and hail. However, they can still bring steady drizzle or light showers, and block out sunlight, which can hamper observations of sun-loving, diurnal reptile species.

Old sayings such as, “Red sky in morning, sailor take warning; red sky at night, sailor’s delight” have a kernel of truth to them. Red skies largely result from airborne particulates (e.g., dust, pollen) that cause the sunlight to scatter differently than it would in clearer conditions. A high concentration of particulates can provide nuclei around which precipitation can form. Thus, particulates observed in the morning, combined with atmospheric heating over the course of the day and its contribution to instability of the air mass, may increase chances for rainfall in the afternoon and evening.

Data Collection

It is important to record climatic observations in the field, even if no herps are found. Provided you are in suitable habitat, recording conditions in which herps are not found may provide valuable information to increase our understanding of activity patterns for various species. Record as much information as your equipment and time will allow. It is easier to pare down extensive field notes later than to wish you had recorded more information. A general guideline can be found by looking at species’ records pages on the North American Field Herping Association database (naherp.com). The weather-related data fields consist of air temperature, surface temperature, sky conditions (cloud cover and precipitation), moon phase, humidity and barometric pressure. Many records do not fully utilize these data fields — help fill in these knowledge gaps! I also recommend recording wind direction and speed when possible; as previously discussed, this is a highly debated factor in herping success and merits further study.

While afield, I utilize one of two methods of data collection, or a combination of both. The first technique is to take spot-data recordings at every herp encounter. However, when conducting an in-depth study of one given locale over several hours (or cruising one stretch of road repeatedly during the night), it can be more practical to take readings at fixed intervals over the period in question.

Even if you don’t have weather data-collection equipment in the field, it is still possible to determine such information post-trip. Many weather websites used in trip planning also have historical information, in some cases hour-by-hour almanac data. Even if you cannot (or forget to) record relevant data at the time and location of that gray-banded kingsnake find, you can access the almanac information when you return home. Keep in mind that historical information is for a given weather station, which may record substantially different conditions than were found at your herping location, depending on the distance and/or change in elevation between the two.

With the information in this article, and data collection equipment in hand, you are ready to head afield to observe your favorite herps with (hopefully) a greater chance for success. You also have the means to gather additional information to increase our understanding of the habits of these interesting creatures. In addition, I hope the information presented here gives you another aspect of being outdoors to observe and appreciate. Good luck!

CHRIS MCMARTIN is a navigator in the U.S. Air Force, a SkyWarn-certified storm spotter and an avid herper. His main interests are lizards of the American Southwest. Among other herps, he still has the box turtle that was given to him 29 years ago, and he also breeds banded geckos.