Know your snake inside and out with this snake gastrointestinal tract anatomy overview.

Gastrointestinal Tract of the Snake

For the most part, the mouth does little more than catch food for the snake. Very little chewing, if any, occurs. After a snake catches its prey, its kinetic (moveable) skull “walks” the jaws in a stepwise fashion, ratcheting the prey deeper into the throat until ultimately it’s swallowed.

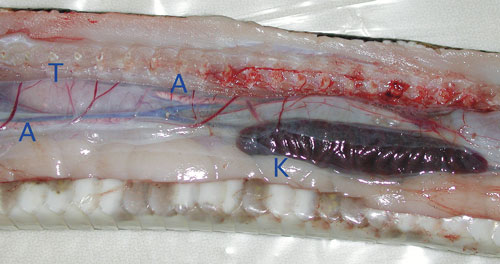

Photo courtesy Mader/Wyneken Collection

Found in the fourth quarter of the snake are the adrenals (A), a testis (T) and the right kidney (K).

Saliva produced has little digestive significance; its role is mostly to serve as a lubricant. The esophagus courses alongside the trachea and extends from the back of the mouth to the stomach. Its longitudinal folds allow for great stretchability to accommodate large food items.

The junction between the esophagus and the stomach is clearly noted at a site approximately equal to three-fourths the length of the liver. Long and tubelike in shape, the stomach ends in a tight valve called the pylorus, where food is dumped into the first loop of the small intestine called the duodenum. The duodenum is found just after the end of the long, spindle-shaped, dark-brown liver.

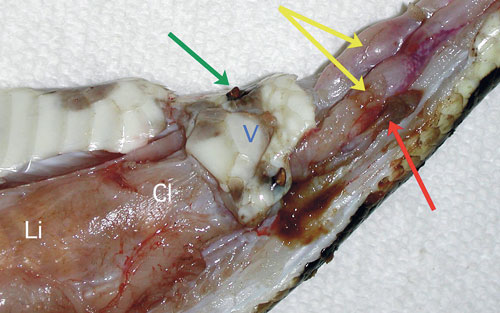

Photo courtesy Mader/Wyneken Collection

Found in the tail region are the large intestine (Li), cloaca (Cl), vent (V), vestigial pelvic limbs or spurs (green arrow), hemipenes (yellow arrows), and scent gland (red arrow).

In snakes the small intestine is usually straight, but some species may have short transverse loops. The small intestine terminates at the junction with the large intestine. A cecum, a small appendage between the small and large intestines, is present in some snake species. It is not known why some snakes have a cecum and others do not, but the appendage is generally found in herbivorous animals but not in carnivores.

The large intestine ends at the cloaca, a three-chambered structure with multiple functions. Feces is discharged from the large intestine directly into the cloaca’s forward chamber, which is called the coprodeum. The middle chamber, called the urodeum, receives the urogenital (urinary and reproductive) ducts, which carry urine and either eggs (females) or sperm (males). The proctodeum, the posterior chamber, acts as a general collecting (mixing) area for digestive and excretory wastes. The male hemipenes open into the portion of this compartment nearest the tail, and both male and female snakes have scent glands that also open in this location.

Like mammals, reptiles have relatively advanced (evolutionarily speaking) metanephric kidneys. They are situated in the rear part of a snake’s body attached to the inner wall with the right kidney in front of the left. They are brown and consist of 25 to 30 lobes. These look like a stack of pennies that have been knocked over.

Because snakes lack a bladder, the ureters leave the kidneys and open directly into the urodeum. Just before entering the urodeum, the snake’s ureters widen, which acts as a urine storage organ.

Snake Respiratory System Anatomy>>

Snake Cardiovascular System Anatomy>>