Through the publication of my research paper on gout in Odatria, I’ve read and learned a lot about herptile urology, or the study of the urinary tract

Through the publication of my research paper on gout in Odatria, I’ve read and learned a lot about herptile urology, or the study of the urinary tract. This, in addition to my 2-year-old Golden Retriever dealing with kidney disease since she was a puppy, has made this an area of medicine I really want to dive deeper into. This article plans to discuss herptile renal disease, how it develops, what clinical signs are, and what can be done to minimize it.

Before we discuss renal disease, we’ll need to discuss normal physiology. The function of the kidney is to filter the animal’s blood and to remove nitrogenous wastes from the body. Nitrogenous wastes accumulate in the body due to the breakdown of dietary protein or normal homeostatic mechanisms such as recycling endogenous (produced by self) proteins or nucleotides. They are metabolized in the liver first from ammonia and then moved to the kidneys for expulsion from the body.

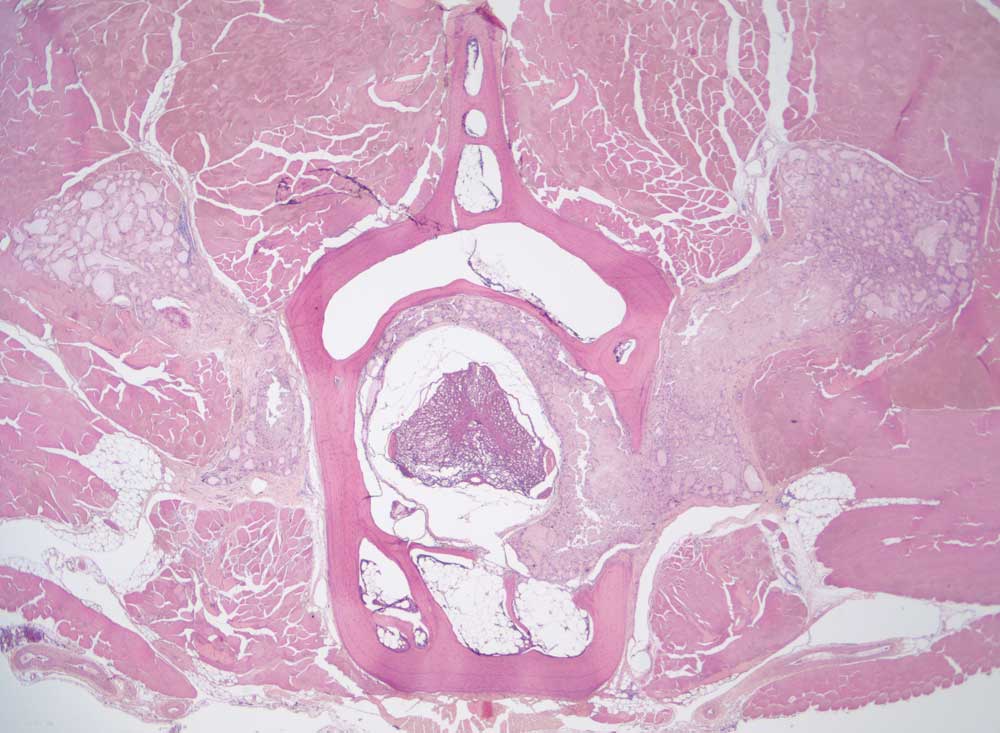

The herptile kidney is the same over much of the different groups. The herptile kidneys are made up of many nephrons (the functional unit of the kidney) where filtration of the blood occurs. A major difference between herptile kidneys and mammalian kidneys is the lack of a portion of the nephron called the loop of Henle. This allows mammals to create extremely concentrated urine and retain water. Without this, herptiles can only create urine that is as concentrated as their blood. This is why terrestrial herptiles (lizards, snakes, some species of frogs, etc.) produce uric acid instead of urea, as this is a highly insoluble material and allows the herptile to expel nitrogenous waste without losing excessive water.

Obstruction removed

Additionally, certain herptiles have salt glands that also aid in removing excessive salts from the body without losing water. Certain herptiles will use urea as their main nitrogenous waste product, and purely aquatic amphibians will use ammonia. Regardless of nitrogenous waste produced, the kidneys lead to ureters which will then either go to a urinary bladder first (if present) or directly to the urodeum in the cloaca. Another important factor when evaluating herptile urology is the renal portal system, wherein blood from the back half of the animal hits the kidneys first before returning to systemic circulation. This is why many veterinarians give injections into the front half of the animal to minimize the drug going directly to the kidneys, where it’ll be either excreted immediately or directly damage the kidney.

Renal disease in reptiles can be caused by a variety of reasons. Essentially anything that affects kidney function can induce renal disease. This can be husbandry related factors such as chronic dehydration, inappropriate temperature gradients, or excessive dietary protein, which I evaluated extensively in my gout paper (I also once saw a sulcata tortoise that developed gout when he got into the owner’s duck food without them knowing), toxic changes to the kidneys secondary to drugs such as aminoglycoside antibiotics, congenital changes in the kidneys, degenerative changes to the kidneys with age, neoplasia, kidney infections (pyelonephritis), and any systemic disease altering kidney. Renal disease in herptiles can present with very unspecific signs—lethargy, inappetence, and weight loss.

Tail Amputation: Care After Surgery

Other signs such as fluid buildup on the body (coelomic effusion), a urinary bladder stone in those species that can or a swollen, painful digit indicative of gout. For herptiles that produce uric acid, gout can be a manifestation of chronic renal disease, as uric acid not able to be filtered by the kidney can precipitate into other parts of the body.

Diagnosis of renal disease in herptiles is complex. As with other diseases with these taxa, reviewing husbandry and exams of the animal are clues that can indicate abnormalities. Bloodwork can oftentimes be unrewarding, as serum uric acid can often remain normal despite significant renal disease, and I will use other values like phosphorous, calcium, and electrolytes to help assess the health status of the kidney. Radiographs and other imaging modalities (CAT scan, ultrasound) can help assess if there is coelomic effusion, bladder stones, and the structure of the kidney. If there is a swollen digit, cytology can reveal the presence of gout. In general, renal disease is not something that can be reversed, and eventually will progress despite medical management. An exception is surgical removal of diseased portions of the kidneys (a nephrectomy), which is a viable option in snakes, and removal of a bladder stone.

Even in these cases, medical management is necessary to minimize progression and recurrence of this disease of the rest of the kidney. Ensuring proper husbandry—especially with temperature and humidity gradients, is key to supporting the reptile’s metabolism and function of the kidney. Hydration needs be prioritized with daily warm water soaks, injecting/spraying prey items with water, and creating water droplets for the herptile to drink. Medications may be necessary, and if gout is present, medications such as allopurinol can be used to reduce the buildup of uric acid crystals and pain medications should be given to provide comfort, as gout is incredibly painful. Prevention of renal disease in herptiles comes from doing sufficient research on the husbandry of any species and yearly exams on your herptile with a qualified reptile veterinarian.

Eric Los Kamp, DVM, is an exotic animal and wildlife veterinarian at Winter Park Veterinary Hospital in Winter Park, Florida who has aspirations to board certify in reptile/amphibian medicine. In addition to being a member of the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians (ARAV), he is an avid Ackie monitor keeper.