Coral snakes are secretive and seldom seen.

"Red to yellow, kill a fellow; red to black, venom lack," so goes the old saying. This method of remembering the color sequence of a coral snake works pretty well throughout most of the United States. In fact, it seems to define U.S. coral snakes everywhere but in the northern Florida Keys. On Key Largo, for example, the colors of the eastern coral snakes (Micrurus fulvius) are muted and most, if not all, of the yellow rings are lacking. Often the sole yellow ring visible on Key Largo coral snakes is on the rear of the head. Otherwise they are banded in a rather dull red and black.

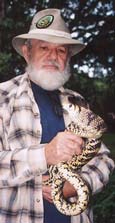

Photo by Dick Bartlett

The old rhyme "red to yellow, kill a fellow" works with most U.S. coral snakes, including this eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius), but the rule is not ironclad.

But that's not the case near my home in north-central Florida. On several occasions I've investigated motion amidst the fallen leaves just outside my window and often found a vibrantly colored eastern coral snake with bright yellow rings separating the red from the black.

Coral snakes are a fact of life where I live. They are common but secretive and seldom seen. During the summer months, when we north-central Florida residents normally have some rainfall every few days and high humidity renders the leaf litter moist and pliable, coral snakes are often diurnal and surface active. They move over the ground with their noses poking and prodding for other snakes, the principal repast of coral snakes.

Florida Coral Snake Color Morphs

The eastern coral snake comes in at least three distinct color phases in south Florida. Besides the phase clad in red, yellow and black rings and the red-and-black upper Keys morph, there is the one that I call "the broad-red-banded morph."

This latter type seems restricted to the southern tip of the Florida peninsula and is quite distinctive. Rather than having the red-and-black bands of about the same width (the yellow rings are always narrow), this snake has red bands about twice the width of the black. It also lacks most or all of the black scales that occur in the red fields of the normal morph. This beautiful snake is rarely encountered. I've yet to find one afield. In fact, the only examples I've ever seen were at The Shed (a Miami pet store that's been out of business for years).

I've never been able to go into the field with a feeling of certainty that I'll find a coral snake of any species. Rather, I have always considered them fortuitous finds, completely incidental to whatever my main purpose afield is. I've gone out looking for crowned snakes (a favorite coral snake food) and managed to stir up one or two corals while puttering around. On another occasion, I went looking for peninsula mole skinks and found a big eastern coral beneath a board I turned.

South American Coral Snake Species

My luck in not finding coral snakes on cue follows me from the American Southeast into Amazonian Peru. In Peru, coral snakes diverge from what we Americans have come to consider the "normal" suite of coral snake characteristics. In Peru, coral snakes may be typically ringed and colored in red, black and yellow (or white). Others may have double bands of black, at least one lacks red bands and a few species lack rings almost entirely. In these latter types the dorsum is black, the belly is banded in orange and black, and there is usually a single band of orange on the head and two or three bands of orange on the tail.

Photo by Dick Bartlett

The aquatic coral snake (Micrurus surinamensis) is one of the largest coral snakes. These South American natives can reach 6-foot lengths and spend much of their time in or near water hunting for eels and knife fish.

A very beautiful Latin American coral snake, Micrurus langsdorffi, has broad bands of orange rather than red.

Latin American coral snakes (others include the sooty coral snake, M. putamayensis, and the Amazonian coral snake, M. spixii obscurus) also occur in habitats very different from their U.S. relatives. Most are terrestrial inhabitants of forested and/or disturbed areas, but a few show a decided preference for boggy areas. One is so persistently associated with water that it's dubbed the "aquatic coral snake." This huge creature (adults reach 6-foot lengths) is M. surinamensis, and its preferred prey are synbranchid eels and knife fish.

Aquatic Coral Snakes

Young Cage accompanied me on my last trip to Peru. He most wanted to see a tropical coral snake.

A post-dusk hike along one of the shorter trails in the preserve brought us to a little stream that we forded. There, lying coiled against a partially submerged log, was a 41Ú2-foot-long aquatic coral snake (M. s. surinamensis). There were several large knife fish in the pool, probably its intended food. Even though we managed to bump into a nest of hornets while catching the snake for photographs, Young and I were both happy campers because of the find.

The aquatic coral snake has turned out to be the Amazonian species that we see with the most regularity. It is bright red, black and white, and the head shield is narrowly bordered in black. We have found babies at night in water buffalo wallows and several larger ones in muddy streams and at swamp edges. One, a 3-footer that we surprised at the edge of a trail, dove headfirst into the mud and disappeared with an alacrity that had to be witnessed to be believed. Poke and prod though we did, we never saw the snake again.

Pygmy and Ribbon Coral Snakes

On another trip, Dale Sylvester's attention was caught by a bit of orange that repeatedly appeared then disappeared amidst the fallen leaves. Patti and Devon were with him, and together they managed in the forest gloom to determine that the writhing tail of a tiny snake caused the flashes of color. Despite its lack of banding, it proved to be a pygmy coral snake (Leptomicrurus scutiventris), which is the tiniest micrurine to occur in the area. The snake bore only a couple of orange rings, but when disturbed it quickly flattened, lifted, curled, then uncurled its tail. Were it not for the semaphore effect of the tail, the snake would have gone unseen.

Photo by Dick Bartlett

The pygmy coral snake (Leptomicrurus scutiventris

) is one of the tiniest coral snake species to occur in the Amazon.

Photography by Dick Bartlett

A western ribbon coral snake (M. hemprichii ortoni) was also recently found on the trail at Madre Selva. This small and very slender coral snake is vividly ringed in typical coral snake colors of red, black and white. The one we found was a baby, barely 16 inches in length, and it never made a single effort to bite. This is very unlike the aquatic, Amazonian and sooty coral snakes that never miss an opportunity to try to bite.

Made in the U.S.A.

Now back to the coral snakes of the good old United States. Besides the eastern coral, there is a south-central and a Sonoran species.

The former is the Texas coral snake (M. tener). It is very similar in appearance to its eastern relative, but the ranges of the two are not contiguous. It is another of the slender forms but may attain a length of more than 3 feet. Both albinos and melanistic examples of this snake have been found.

Photo by Dick Bartlett

The Arizona coral snake's (Micruroides e. euryxanthus) venom is similar to that of a cobra, but because of its small mouth and fangs it poses less of a threat than the many species of rattlesnake that inhabit the same area.

The southwestern species is known as the Arizona coral snake (Micruroides e. euryxanthus), the sole species in its genus. Although known for a mild disposition, the venom of this species is dangerous, and becoming overly and carelessly familiar with this little snake is inadvisable.

The Arizona coral snake is a desert species that may be found crossing aridland roadways after dark. However, there's a whole lot of Sonoran Desert out there and comparatively few roads transecting it. So finding an Arizona coral snake is rather like encountering that oft-spoken-of needle in the proverbial haystack.

In 2003, Brad Smith and I happened to be in just the right spot at just the right time. Lulled to complacency by the long drive, I was jarred back to reality when Brad screamed, "Snake!" I skidded to a stop. Brad piled out and hollered, "Coral! Coral! Coral!" Sure enough, crawling rapidly across the pebbly road was a 16-inch-long Arizona coral snake.

Fair Warning

Coral snakes, be they large or small, meek or irascible, all have small but well-developed, permanently upright front fangs. They usually grasp and chew their prey to effect an envenomation. Treat these snakes as you would any other venomous snake – very, very carefully. Although the chances of being accidentally bitten by a coral snake are far less than being bitten by a viperine species, being envenomated by one of these cobra relatives can have frightening consequences.

About The Author

R. D. (Dick) Bartlett is the author of more than 500 articles and author or coauthor of 40 books, including titles on herp care and reptile and amphibian field guides. Two of the most recent titles are “Reptiles and Amphibians of the Amazon: An Ecotourists Guide,” and “Florida’s Snakes: A Guide to Their Identification and Habits.”

Bartlett travels extensively, both to find and photograph herps in the field and to present multi-projector reptile and amphibian oriented screen tours. In 1970 Bartlett began the Reptilian Breeding and Research Institute (RBRI). Since its inception, more than 200 reptile and amphibian species have been bred at this private facility, some for the first time in the United States under captive conditions. Bartlett also leads herp photography trips to the Peruvian Amazon for Margarita Tours (www.amazon-ecotours.com).

*This article first appeared in the September 2004 issue of Reptiles magazine.*