This herping trip to Mexico uncovers reptiles and amphibians.

In two vehicles we headed along paved roads and out of the city of Alamos, in Sonora, Mexico. We continued on meandering dirt roads, across a deepening river and onto a one-vehicle-wide track that had been graded from the sheer mountainside. At each pinnacle we were provided with an eagle's-eye panorama of the city far below.

On a map of these roads, what looked like a drive of less than an hour, stretched on and on for close to two hours. Dusk was upon us before we arrived at the village, valleys were already deeply shrouded in inky cloaks and the last lingering rays of the setting sun silhouetted the peaks. Stephanie, an exemplary guide, provided us with a wonderful botanical and ornithological commentary throughout the drive. She even provided the highlights by two-way radio to the other car.

The setting was picture perfect, but it wasn't quite what we hoped for. We wanted to herp, but the mountains were already becoming cold, and there were no real roads for road hunting. We elected to drive back toward Alamos, hoping that once we got back to the larger dirt road that we might see some herps of interest. Of course, that meant snakes for Brad and nearly anything for me.

On our way back through the mountains, we stopped at some tiny rivulet-fed ponds – puddles almost – and found a few calling Sabinal rain frogs (Leptodactylus melanonotus) and a pretty leopard frog (Rana magnaocularis) with relatively big eyes.

Once we hit the big road, a few of what we were now calling the "common frogs" – Mexican treefrogs (Smilisca baudini) and Great Plains narrow-mouthed toads (Gastrophryne olivacea) – were chorusing from roadside puddles.

Sinaloan Treat

Just before we reached Alamos, we found one of the trip's highlights: a beautiful adult Sinaloan milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum sinaloae). I last saw one of these magnificent tricolors nearly 40 years ago. A long hiatus, but worth the wait. There was something exciting and different about seeing this herpetocultural favorite in the wild, rather than in a hobbyist's terrarium.

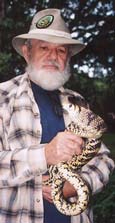

Photo Credit: Dick Bartlett

The Sinaloan milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum sinaloae) is one of 25 subspecies of American milksnake.

Like the last few nights, amphibians were everywhere but reptiles were at a premium, at least for us. Strangely though, Young and Matt Cage were seeing one snake species right after the other. Brad and I would find 100 frogs; the Cages would find a snake. Brad and I would find another 500 frogs; the Cages would find another snake.

However, it was Brad's and my night to find a beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum exasperatum). And it was a pretty one, way over 2 feet in length with lots of yellow on the otherwise black-beaded scales.

We almost didn't stop for the creature, as one of the intercity buses destined for Alamos had just passed and we felt certain that anything on the southside of the road was no longer alive. But you just can't drive past a beaded lizard, alive or dead. So, downpour or not, bus or not, we stopped. When Brad hopped out to check the beast, it got up and started to walk away.

Little-Known Snake

Brad blamed the paucity of reptiles on me and I on him, but the result was the same few reptiles. And it remained that way for the remaining two days. It was just one of those trips. We did see a Mexican short-tailed snake (Sympholis lippiens) crossing the road just as an approaching string of traffic drew near. It escaped seemingly unscathed. Matt and Young were luckier. They found two and, thankfully, invited Brad and me to photograph them. I was delighted for this was a snake species that really intrigued me.

Photo Credit: Dick Bartlett

This 30-inch-long Mexican long-nosed snake (Rhinocheilus lecontei antonii) is much more brightly colored and precisely patterned in black, red and white than its U.S. cousins.

There is little known with certainty about this snake. That it is patterned for its entire 15- (or so) inch length in bands of jet black and creamy yellow is obvious. That it is of reasonably heavy girth, has a proportionately short tail and feels rather yielding and flaccid when lifted is almost as obvious. But beyond these things everything about Sympholis is conjectural. It is probably a secretive burrower that comes topside primarily when forced to do so by monsoon rains flooding its burrows. There is virtually nothing known about its diet or reproductive biology.

Our fortunes began to change ever so slightly. First, we found a Mexican long-nosed snake (Rhinocheilus lecontei antonii), and it was big – maybe 30 inches. This is a spectacular snake, much more brightly colored and precisely patterned in black, red and white than its stateside cousins. The next night we found a second one, smaller but every bit as pretty. On the sunny mornings, the spiny-tailed iguanas (Ctenosaura hemilopha) were actually abundant. In the afternoons swifts and spiny lizards of several species basked.

MIAs

There were several species we hoped to see that were conspicuously absent – creatures I saw long ago, when I last visited Mexico, or otherwise knew existed in Sonora. Aided by some range maps I stumbled across on the Internet, I mentally began an "I wonder where it is" list.

Where was that most beautiful of hook-nosed snakes, the thornscrub hooknose (Gyalopion quadrangulare)? Friends found the little burrower in fair numbers near Alamos without even making a concerted search. Yet, despite the fact that I searched long and hard for this strawberry, black and white snake both in its limited Arizona range and again here in Sonora, I was not yet lucky enough to have one cross my path.

Photo Credit: Dick Bartlett

There is virtually nothing known about the 15-inch-long Mexican short-tailed snake's (Sympholis lippiens) diet or breeding habits.

And where was the file-tailed groundsnake (Sonora aemula)? For years this variably banded red, black and white burrower has been sitting very near the top of my "wannasee" list. Again, though we were now in the heart of its range, we found no examples of this little insect-eater with the curiously roughened caudal scales.

And what about the big, often feisty, Mexican West Coast rattlesnake (Crotalus basiliscus)? This rattlesnake is closely allied to the more familiar black-tailed rattlesnake (C. molossus ssp.) of the American Southwest and northern Mexico.

In previous years I found the impressive Mexican West Coast rattler to be common. We knew the species to be present by the neonates we found dead on the paved roadways, but any large example, dead or alive, alluded us.

Once called the Mexican green rattlesnake, the name "Mexican West Coast rattler" seems far more appropriate. Although some examples did have an overall greenish hue, the ground color of many was yellowish to very pale olive with hints of peach. This is a hefty diamond-backed species of variable disposition. When disturbed some of these rattlers are quiet and laid-back; others are feisty.

Anyone Seen a Cantil?

To find a northern cantil (Agkistrodon b. bilineatus) in Sonora was way up at the top of my very long priority list. In fact, finding a cantil of any subspecies had long been one of my goals. I searched for ornate cantils in northeastern Mexico and failed. I looked for Yucatan cantils on the Yucatan Peninsula and failed. I sought southern cantils in the Guanacaste region of Costa Rica and failed. And on every trip I ever made along Mexico's West Coast I spent some time looking for northern cantils and never found any. In every case I went to the right spots where friends had earlier found each of the cantil subspecies, searched long and hard for the snakes, and seen nary a cantil for my efforts. And so it was on this trip. Failure again – or can I call it magic?

Photo Credit: Dick Bartlett

The author always includes several cantil species, such as this northern cantil (Agkistrodon b. bilineatus), in his herpetological "wannasee" list when searching south of the border, but he's never found one.

Collectively, cantils are nervous, short-tempered snakes. They are primarily snakes of lowland habitats and often associated with rivers, streams and water holes. Cantils are adult at about 3 feet in length (some get to more than 4 feet). They have long fangs and are quite ready to use them in their defense. They are darker in color than copperheads but lighter than adult cottonmouths.

The northern cantil is the darkest of these snakes, varying in ground color from deep russet black to almost black. It has narrow darker bands outlined on each edge by white markings of only one scale in width.

The ornate cantil of northeastern Mexico is the brightest, with broad, light-edged, orange-buff bands against a dark ground color that may near charcoal in darkness at the edges but with vaguely lighter centers.

The Yucatan cantil has white- (or gray-) edged, broad, light-centered russet bands separated by narrower bands of orange buff to terra-cotta.

The southern cantil has a combination of bands of dark and light (but always rich) brownish russet. Vague white markings may separate the two band colors. A population in Guatemala is of dingy, light-and-dark, brownish-russet bands, variably edged with narrow white markings. All cantils have prominent stripes of white on their faces.

I Shall Return

Why do I so consistently fail to find these snakes? But then too, looking for them is a challenge that leaves me with a desire to return to northwest Mexico.

So as we packed our gear in preparation for the long drive home, Brad and I were not only discussing our route northward, but we were already formulating plans for a return to Sonora.

The next trip would, we decided, be extended eastward a bit into Chihuahua and southward into northern Sinaloa. We would allocate two weeks for the trip, spending a few days in the mountains searching for salamanders, some in the lowlands in search of additional toads and frogs, and then head southward into Sinaloa where we hoped to find the remarkable appearing northern shovel-nosed treefrog (Triprion spatulatus). As the time draws near, I feel rather confident that we will add a host of other species to the target list. We never fail to do so.

About the Author

R. D. (Dick) Bartlett

R. D. (Dick) Bartlett is the author more than 500 articles and author or coauthor of 40 books, including titles on herp care and reptile and amphibian field guides. Two of the most recent titles are “Reptiles and Amphibians of the Amazon: An Ecotourists Guide,” and “Florida’s Snakes: A Guide to Their Identification and Habits.” Bartlett travels extensively, both to find and photograph herps in the field and to present multi-projector reptile and amphibian oriented screen tours. In 1970 Bartlett began the Reptilian Breeding and Research Institute (RBRI). Since its inception, more than 200 reptile and amphibian species have been bred at this private facility, some for the first time in the United States under captive conditions. Bartlett also leads herp photography trips to the Peruvian Amazon for Margarita Tours (www.amazon-ecotours.com).