As a veterinarian, I have certainly experienced “miracle” cases—those in which animals survive and thrive regardless of the odds&mda

As a veterinarian, I have certainly experienced “miracle” cases—those in which animals survive and thrive regardless of the odds—as well as “disaster” cases, with patients that crash and burn from even the most seemingly simple problems.

Reptiles do have a propensity to get better, albeit slowly. Perhaps that is why I have been able to excel at what I do: my patients often improve regardless of my actions. But unfortunately, no matter how hard I try, and even if I do everything perfectly, things don’t always work out.

Dozer was a 50-ish California desert tortoise that presented to my hospital for a second opinion on the tortoise’s inability to use its rear legs. The previous veterinarian gave Dozer an injection of a long-acting steroid and sent the owner home with injectable Baytril. After two weeks of this prescribed therapy, though, Dozer still wasn’t using his rear legs. When the first veterinarian wanted to add another antibiotic to the regimen, Dozer’s owner decided to seek another opinion.

Read More From Dr. Mader

How to Recognize and Prevent Medical Ailments in Amphibians

The Vet Report: Sulcata Tortoise Spine Abnormality

The Vet Report: Fluid Therapy in Reptiles

The Vet Report: Inclusion Body Disease

DOUGLAS R. MADER

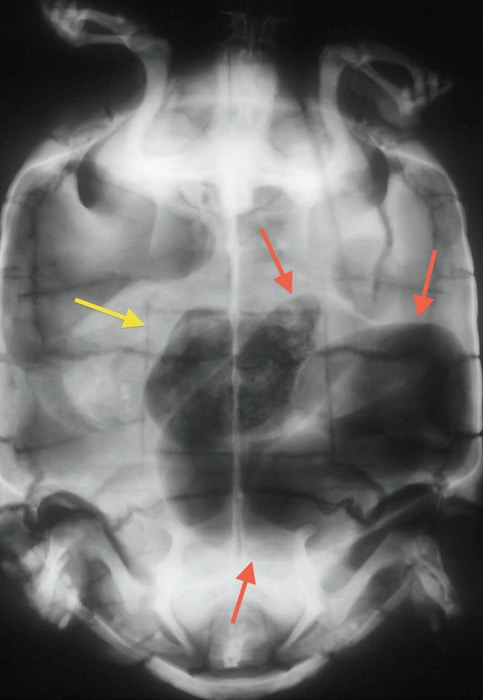

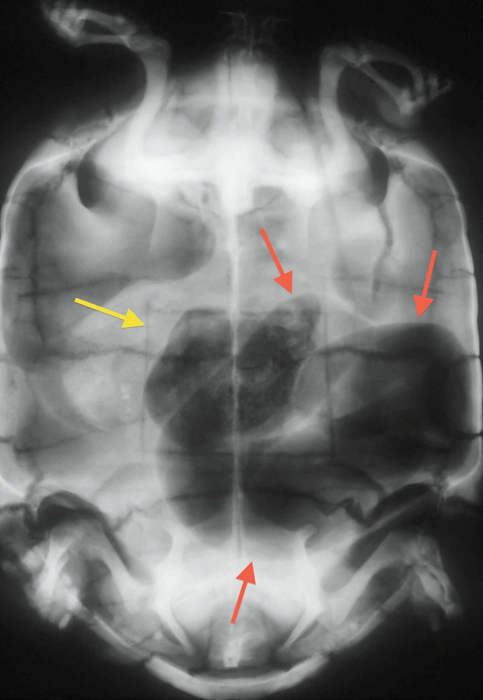

In this X-ray image, the yellow arrow points to the previous plastronotomy cut needed to remove Dozer’s bladder stone. The orange arrows point to the tortoise’s twisted intestines.

After receiving a detailed history from the owner, I picked Dozer up to perform a physical examination, starting with a pre-femoral, digital coelomic palpation. The first thing I noticed was a large, rock-hard mass in the left pre-femoral fossa. I asked the owner if the other veterinarian had taken X-rays and was told no. In fact, I was told, the other veterinarian had not even picked the tortoise up to conduct an examination.

I received permission to take X-rays, and the first thing that was revealed was a huge bladder stone, measuring approximately 6 centimeters in diameter. After I explained to Dozer’s owner that these large calculi were common in desert tortoises, and that the stone was likely the cause of Dozer’s rear-limb paresis, he agreed to let me take the tortoise to surgery for a plastronotomy/cystotomy—a routine procedure done to remove bladder stones from tortoises. It was scheduled for the following day.

The surgery went as expected. There were no complications and no obvious internal damage as a result of the stone. Dozer’s recovery was uneventful, the tortoise was walking within two days post op, and so was discharged with meds—a seemingly successful outcome.

About a week later, Dozer presented for an unexpected follow up. He was depressed, weak and could not walk. Significantly, he was bloated, as well, with flesh puffing out from all four limb holes. I asked the owner what happened and was told that Dozer was doing great for the first two days after surgery, eating well, walking well and being very active. The owner even took Dozer to his monthly tortoise club meeting to show everybody how much improved Dozer was (I cringed at hearing that, as Dozer was less than one week post op).

I was given permission for labs and X-rays, and the latter showed severe intestinal bloating (see above photo). I immediately knew what happened. Dozer’s owner was so excited and proud of his tortoise and the surgery, that when he was at the tortoise club meeting he had flipped Dozer over repeatedly in order to show everyone the plastic patch on his tortoise’s plastron. During all these flips, Dozer had torsed, or twisted, his gastrointestinal tract.

I performed emergency surgery to untwist Dozer’s intestines, and when I opened the patch on his plastron, I saw that the tortoise’s insides were filled with a blackish green, foul-smelling soup. This was suctioned out to reveal a necrotic portion of intestine. I surgically removed the dead intestinal tissue and reattached the remaining healthy portions. After liters of warm saline flushes, Dozer was closed back up. Recovery took much longer this time, as the surgery itself was nearly three hours long compared to the initial 45-minute bladder stone surgery. By the following morning, though, Dozer was up and around, albeit subdued. He was kept in the hospital for approximately a week, with medications and supportive care, and discharged to a very thankful owner with instructions to never flip the tortoise over again. I sent several medications home with them, including a laxative to help keep the contents of Dozer’s bowel loose until everything inside him was fully healed.

All was going well. After three weeks, Dozer came in for a scheduled recheck, and he was active and doing great—eating, walking and defecating. I had the owner discontinue all the medications except for the laxative.

The following weekend, Dozer’s owners went on vacation and left him with a pet sitter. The sitter began having problems administering the oral laxative, and it seemed to her that Dozer was not defecating properly. Rather than call me, she panicked and took the tortoise to a 24-hour emergency clinic. She told the people there Dozer’s history, and how she was administering the laxative, albeit not very effectively. The ER doc, a dog and cat veterinarian, took a radiograph and identified what she thought was constipation. Wanting to help the uncomfortable tortoise, she administered dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DSS), both orally and via the rectum. She then discharged Dozer with instructions for the sitter to monitor his fecal output and report back to her regular veterinarian if there were any questions.

During the night, Dozer developed a massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and he was found dead in his cage the following morning. This is because DSS is known to be extremely toxic to reptiles.

Fortunately—and thankfully—this type of outcome is rare. But it does point out the reality that, as with anything in medicine, every patient is unique and every situation is different. This could not be more true than in reptiles.

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.