About five years ago, I wrote about an experience I had at a national reptile expo. Very few people know what I look like, because my mug shot has nev

About five years ago, I wrote about an experience I had at a national reptile expo. Very few people know what I look like, because my mug shot has never been featured with this column. (I keep telling Russ Case, REPTILES’ editor, that my picture should be on every cover, but he hasn’t bought into that idea). As a result, I was able to mingle and engage many people in conversation, learning a lot about their perceptions of those in my profession.

While I had a great time at the expo, I was dismayed at the random negative comments by the attendees and exhibitors about veterinarians. It seems that, especially with the professionals, veterinarians were generally “not worth the money spent.” I have markedly paraphrased what they said about vets—I don’t think the verbiage would be allowed on the printed page.

douglas r. mader

If you sense something wrong with your reptile, don't wait. Take it to a reptile vet.

I’ve been a veterinarian for more than three decades, and a herp enthusiast for a lot longer than that. Way back when I was a starving student, I lived hand to mouth. Of course, I had several dozen pets—mostly reptiles—and when they would get sick, it was painful to fork over money to a vet to try to get them fixed. I remember discussing, sometimes arguing, with my veterinarian over recommended treatments and costs.

It wasn’t until I crossed the line and went from consumer to provider that I finally understood what was in the “secret sauce,” and this is what I learned: You have to spend money to save (or make) money.

It seems like a simple concept, but can be hard to swallow when faced with it. Here’s a scenario: Let’ say you’re a snake breeder, and one of your snakes stops eating. Because you keep immaculate records, you know that it always eats at this time of year, and nothing has changed in its environment. You don’t want to overreact and run to the vet if it is just a blip on the EKG, so you wait until the next scheduled feeding to see what happens.

A couple of weeks later, you offer food and still no appetite. Okay, you may think, let’s give it a little longer to see what happens, and you try again in two weeks—still with no feeding response. One more time, still no go.

Now it’s been eight weeks since the last time your snake ate. As we all know, some snakes can easily go eight weeks without eating—it’s no big deal—but, your meticulous records indicate that this snake has never gone this long.

So you talk to your friends, check with the high school kid that works at the pet store, and, of course, check the Internet, before deciding to try soaking the snake in vitamin B water for 30 minutes and putting it in direct sunlight prior to feeding it the next time. Oh yeah, and someone on one of the online herp forums suggested putting the snake in a clear sweater box next to another snake’s cage, and letting it watch/hear/smell the other snake eat. All of this should stimulate the snake in question to start eating again.

None of it works.

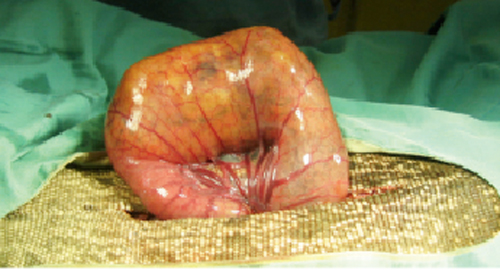

Finally, the snake is now acting lethargic, almost limp. This is one of your best breeders, and against your better financial judgment, you decide to take it to a local herp vet. He/she does a physical examination ($) and notes that not only is the snake weak, there is an obvious lump in its stomach region. The vet recommends some laboratory testing ($$) and X-rays ($$$), and upon examination of an X-ray, discovers a suspicious area in the stomach region. A gastroscopy is recommended, to go inside and take a look, possibly take a biopsy, or, if you’re lucky, remove any foreign material ($$$$).

You decide not to have the gastroscopy done, and, sadly, the snake dies. The vet is very upset that you lost your pet and offers to do a necropsy (animal autopsy) to find out why it died. You don’t want to spend the money now, because the snake is already dead. The vet suggests that it is very important to find out why it died, because you have thousands of dollars’ worth of valuable snakes. You need to find out why it died to make sure that the other snakes are not at risk.

Again, you think, it’s already dead, so it doesn’t matter. I’ve already spent $ plus $$ plus $$$, which equals $$$$$$.

Fortunately, the vet has an energetic, awesome veterinary student intern. The intern asks the vet for permission to perform the necropsy for free as a learning experience. The vet agrees and so do you, so the intern does the necropsy and finds a piece of wood chip bedding that impacted the snake’s stomach, causing a pressure ulcer and gastric rupture.

Sadly, if the snake had been brought to the herp vet when the first signs of illness presented, it could have been treated easily and inexpensively with an endoscopy. Now, instead of having a thriving, healthy, fecund, money-making snake in your collection, you have an empty cage.

It is easier—and less expensive— to prevent a problem than it is to treat one. REPTILES

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (C/F, R/A), DECZM (HERPETOLOGY), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.