I was about 7 years old when I saw my first tortoise. The Central Park Zoo had a nice reptile collection, but for me, there was just that one, enormou

I was about 7 years old when I saw my first tortoise. The Central Park Zoo had a nice reptile collection, but for me, there was just that one, enormous, Galapagos tortoise. It seemed as big as my aunt’s Volkswagen Beetle, older than anyone alive, and as slow as the classroom clock on a Friday afternoon. I watched his keeper feed him a carrot and fell in love.

My aunt wouldn’t get me a Galapagos tortoise then, or for my birthday, for reasons that still make sense to this day. The good news is that although it’s still not practical for me to live with a Galapagos tortoise, there are dozens of species of tortoises, many of which are relatively easy to acquire, house, feed, and care for, even through long New Hampshire winters with which mine have to deal.

When I began to seriously think about getting a tortoise, I did a lot of research, talked with experts, and read everything I could find about living with tortoises. I’m sharing what I’ve learned, through research along with knowledge and experience gained through years of living with these amazing creatures, in an effort to help you decide two things: one, whether or not a tortoise is right for you; and two, which type of tortoise would best suit you (and vice versa).

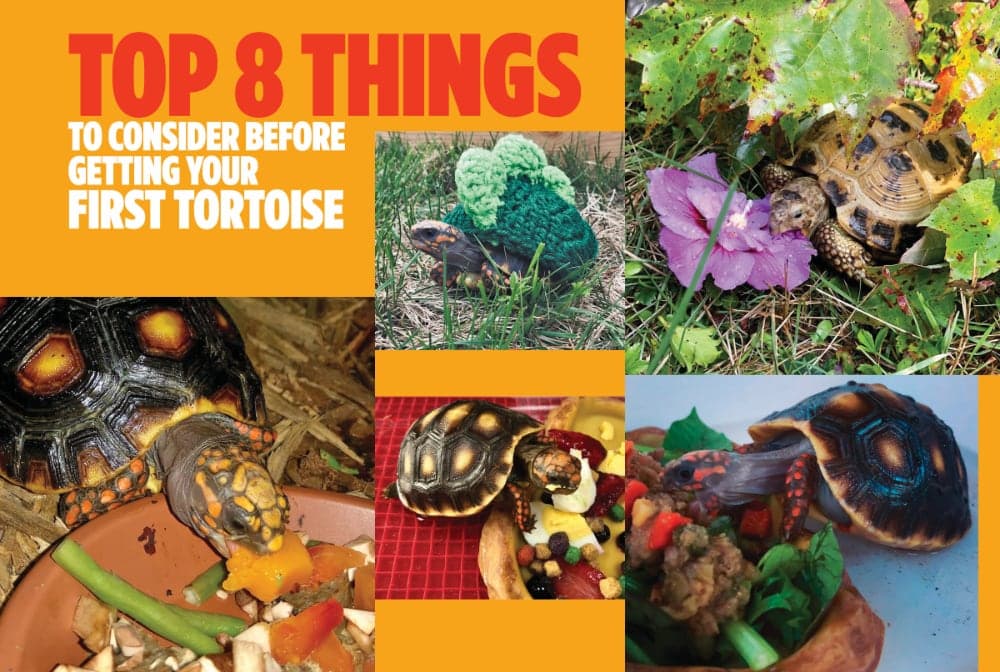

Is a Tortoise Right for You?

The fact that tortoises have changed very little in the last several hundred million years is both good news and bad news, both what makes them really cool animals to live with and learn from and also really difficult animals to live and bond with at home.

The author’s Russian tortoise eating dandelions.

I think most of the difficulties and sad stories you hear about tortoises in captivity grow from people thinking of these little dinosaurs in much the same way that they think of the dogs and cats humanity had been living with for the past few thousand years. If you can get away from that thinking and stop thinking of them like slow, up-armored cats and dogs, you’ll be closer to really understanding tortoises and to living with one (or more) of these amazing creatures for your whole life.

Keeping a Turtle? Here are Some Tips All New Turtlekeepers Need To Know

Red-Footed Tortoise Care Sheet

When bringing tortoises into your life, the most important things to consider between them and humans (and also cats and dogs) has to do with energy input and output; the gulf between cold-blooded and warm-blooded is the reason for most of the difficulties “tough as tanks” tortoises fail to thrive in people’s homes. Tortoises cannot produce or shed heat as humans can, and once their systems get outside a certain temperature range, things like digestion and their immune systems basically stop working. If you can get past that limitation, establish an environment for them in which this most basic need is met, they’re incredibly tough. Once you adjust your thinking and expectations, living with tortoises is a fascinating, entertaining, and beautiful view into a world entirely unlike the world of the warm-blooded; a peek behind the curtain into the age of dinosaurs that will be immensely rewarding for you.

2. Which Tortoise?

There are dozens of species of tortoises, but most of them are unsuitable as a first tortoise for one or more of the following reasons: too difficult to care for, too large, or rare/endangered/protected. My recommendation is to start with either red-footed tortoises (an omnivorous tropical species from South America) or one of the herbivorous temperate species from the Mediterranean, including Russians, Greeks, Hermanns, Marginated, or Egyptians; for brevity’s sake, I will discuss care for my Russian since the care requirements for all the temperate species are similar.

A smaller outdoor enclosure. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

The temperate species brumate (reptile for hibernation) in the wild, but don’t need to; I don’t do it with mine. Redfoots don’t brumate. There are other species of tortoises ideal for those new to tortoise keeping, but we’ll keep it simple and talk about these ones.

3. Finding the Best Tortoise for You

The most common and easily acquired species in my experience are Russians and Redfoots. Remember, the initial cost is only a small fraction of the lifetime expense of owning a tortoise. Some chain pet stores and some of the dealers at reptile expos are notorious for poor care conditions and sickly specimens, so unless yours is the exception, it’s better to find another source. Reputable breeders and dealers around the country can ship a tortoise to you overnight, so don’t feel that you have to find your tortoise locally. Another option is online groups and listings for the rescue of tortoises; you’re taking a chance with these animals, but all four of the Russians in my creep (the name for a group of tortoises) are rescues, found online.

4. Should I Choose a Hatchling?

The Redfoot I live with, Darwin, came to me as a hatchling, and she’s increased her weight by more than 40 times in her first two years with me. It’s been incredible to watch her grow from a tiny hatchling the size of an apricot to a youngster as big as a turkey. The downside of starting with a hatchling is that they’re much more delicate, need higher levels of humidity, and are more sensitive to temperature variations.

The author’s red-foot tortoise, Darwin, came to him as a hatchling. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

Chili, the first Russian I rescued, came from a well-meaning person who’d been keeping the tortoise under awful conditions for 20 years: too small an enclosure, wrong foods, inadequate heat, and light. Luckily, Chili was an adult when he went to live with this person, so he was pretty tough and managed to survive under these conditions. Chili has become much more active and looks better since coming to live with me. You’ll ultimately have to decide if raising your tortoise from a hatchling is worth the extra risk and challenge versus obtaining an adult.

5. Tortoise Enclosure Size

Darwin’s indoor enclosure. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

The subject of enclosure size for tortoises is tricky, bigger is almost always better, but the limitations of indoor space often get in the way, especially in places with a long, cold winter like New Hampshire. Hatchlings can deal with much smaller enclosures, so a big aquarium or plastic container (40G equivalent or more) will get you through the first year or two. Once the tortoise is past the hatchling stage, though, they generally need much more room if they are to stay healthy, more like 12-24 square feet. Here are some enclosure options I found:

- I found Darwin a retired 2.5-foot x 8- foot plexiglass aquarium on Craigslist ($100)

- I built Chili a 3-foot x 4-foot table out of a sheet of PVC from Home Depot and he does well in it ($100)

- I bought a 300G Rubbermaid stock tank from a local farmer and my three Russian females live in it together ($60)

- I bought a 6-foot x 3-foot Vision reptile enclosure from a local person who decided they didn’t want to keep snakes anymore ($150)

- These enclosures meet my creep’s needs, but as the weather warms, I get my tortoises outside on sunny days in the summer in large corrals made from boards from Home Depot ($50).

When the weather warms, the tortoises stay outdoors. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

6. Caring for Your Tortoise

The basics of tortoise care include heat, humidity, UVB, and food. If you are aware of the conditions under which your tortoise does well and can consistently provide those conditions, the tortoise will thrive.

Every tortoise has a temperature range within which they do best. With my Redfoot, I aim for 85 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) throughout the enclosure and allow for some natural variation between day and night. With my Russians, I have a basking zone that reaches 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) in the daytime and keep the cool side of the enclosure above 65 degrees Fahrenheit (18 degrees Celsius) at all times.

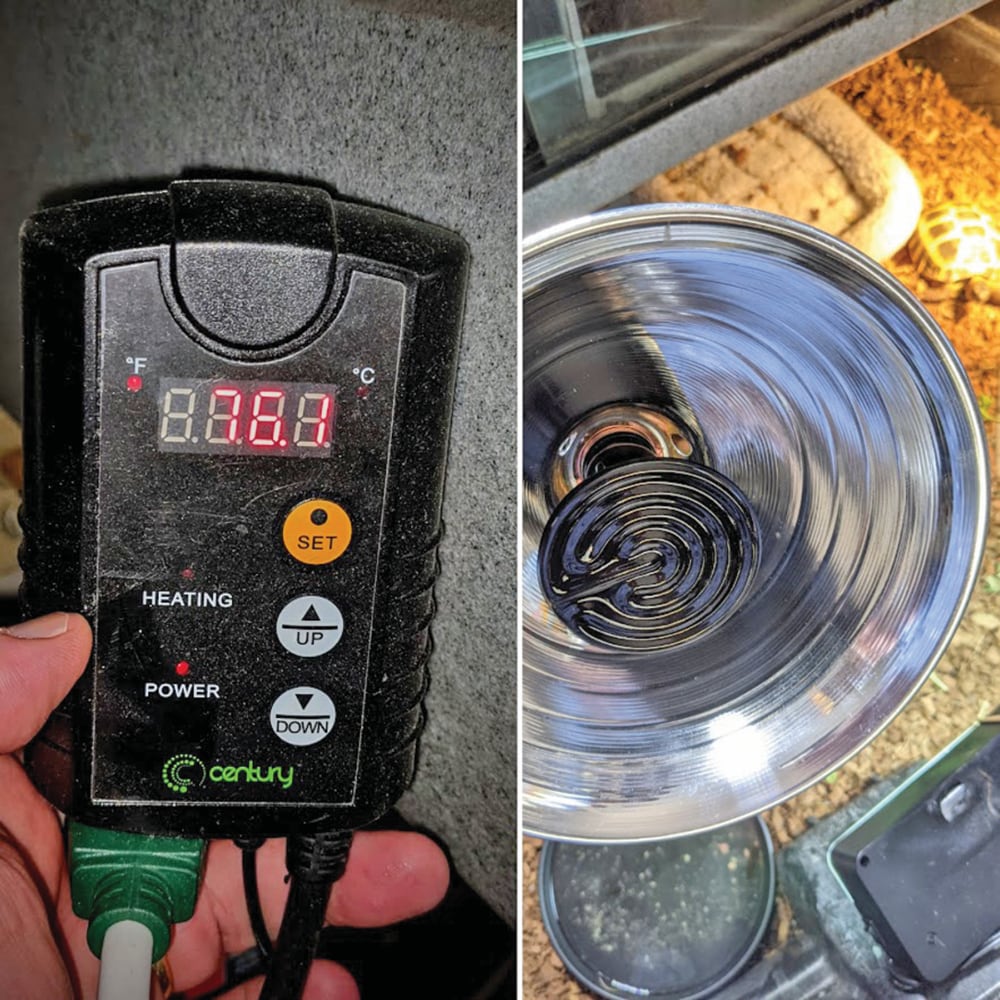

Ceramic heat emitters and a controller help to ensure optimal heating. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

I control the heat in the enclosures with ceramic heat emitters (CHE); I run the CHEs through thermostats set at the desired temperature, and check the temperature at different times of the day and in different parts of the enclosure to make sure I’m actually providing temperatures in the optimum range for my tortoises.

High humidity (70 percent and above) is very important for all tortoise hatchlings in their first year of life; beyond that age, it’s more important for Redfoots than for Russians. The best, and really only, way to keep humidity high in a tortoise enclosure is to be able to close it off, to seal in the humidity with a lid of some sort. The substrate used in the tortoise enclosure can also help with maintaining humidity, I use cypress mulch and coconut husk four inches deep with all of my tortoises and wet it down with warm water each week. Large and shallow water bowls are another method of providing humidity as well as drinking water for tortoises; I use 9- or 12-inch plastic underpots. Another way to ensure hatchlings get the moisture they vitally need is via daily soaks in warm water for their first year.

Chili basking under the heat lamp. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

Lighting in enclosures serves three functions for tortoises: heat and UVB and maintaining circadian rhythms. In my Redfoot’s enclosure, I use a fluorescent UVB bulb on a 12:12 timer, since she doesn’t need to bask. For the Russians, I use both a fluorescent UVB bulb and a mercury vapor bulb, which provide both heat and UVB; they’re often sprawled out under the mercury vapor bulbs, again on a 12:12 timer. It’s not absolutely necessary to use timers for lighting in your enclosures, but it’s a minor expense that guarantees consistent lighting, even when you’re away or busy with other things.

The diets of Redfoots and Russians (or any of the temperate species) vary significantly, but greens play a huge role in both. Weeds, flowers and grasses are wonderful for them, but in New Hampshire, those are unavailable for more than half the year, so I feed mixed greens from the supermarket. I give each tortoise a handful about the size of their shell each morning, then go to work on the rest of their meals. I give the Russians some butternut or spaghetti squash, or pumpkin, about a tablespoon each, one to two times a week; also a similar amount of kibble (Mazuri and Zoo Med) one to two times a week.

The author’s redfoot, Chili, munching on some tortoise kibble. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

The Redfoot, more omnivorous, gets the veggies and the kibble, but also gets fruit (normally papaya, mango or kiwi) one to two times a week and animal protein once a week (I’m currently using a raw dog food, which has 95% meat, organs and bone, the remainder made up from fruit and veggies). That’s just the basic diet. Variety is important, so I add other ingredients as the market and season allow. In summer all of my tortoises eat a lot of dandelions and hibiscus flowers. There are supplements available to help ensure that your tortoise is getting optimum nutrition, but I prefer to just shake a bit of dried plant matter over the greens I give the tortoises each morning, like a salad dressing; I ordered organic opuntia flour and dried hibiscus flowers and wakame seaweed online, which saves money and has both better and fewer ingredients than other supplements.

Getting the basics of care established for your tortoise can seem daunting at first, but once the enclosure is set up and your routine established, it becomes much easier.

7. Tortoises Require Lifelong Care And Can Outlive You

The most important thing that can be said about emergency tortoise care is that it pays to have a reptile veterinarian picked out ahead of time. Once a tortoise has been living with you a while, under a regimen of proper care, very little is likely to go wrong. The riskiest times are when your tortoise has just arrived or when something interrupts consistent care; in either case, the best thing you can do is bring the enclosure back into the desired range of environmental conditions, maybe raising the temperatures by 5 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) and offering the tortoise an additional warm water soak.

Darwin gets a soak. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

If the tortoise is consistently losing weight over time, your veterinarian will test a stool sample and likely prescribe an anti-parasitic; if breathing is whistly or the eyes and nose are snotty, they may have a respiratory infection, which again calls for a visit to your vet, and probably antibiotics for the tortoise. I have a small first aid kit on hand with betadine, Q-tips, and an antibacterial for cuts and scrapes; also, I’ve had success with athlete’s foot cream as an effective treatment for patches of fungus on the shell, which happens with overly soggy substrate in the enclosure.

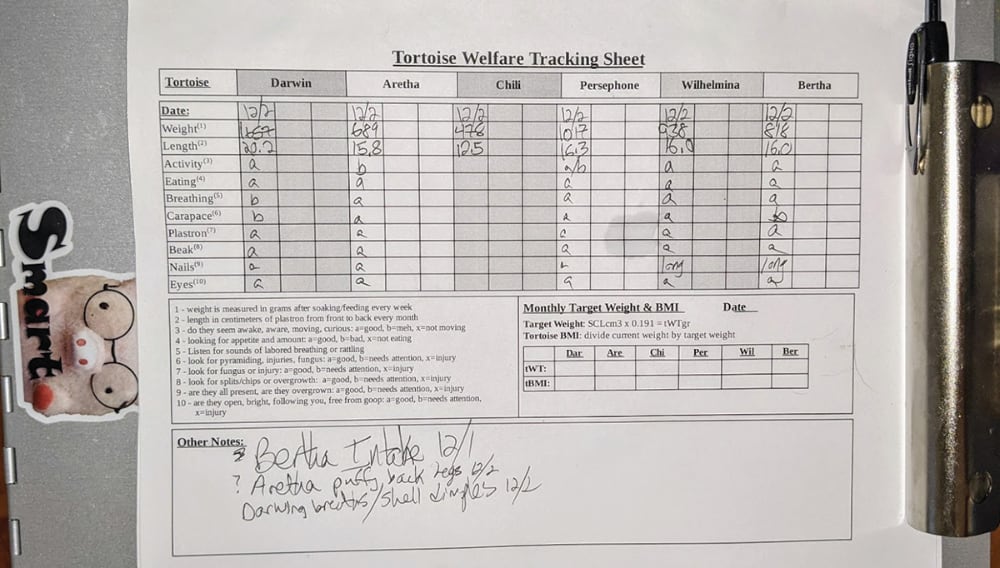

A health chart is critical to ensure your care regimen is up to date. Photo by Jamie Sheffield

Once a month, normally the first Monday, I soak, weigh, and measure all of my tortoises, evaluating them for weight, length, activity, eating, breathing, shell, beak, nails, and eyes. Giving them a thorough examination regularly ensures that I check to see how they’re doing, note if there are any issues carrying over from month to month, and alerting me to warning signs of possible trouble down the road.

Unlike a goldfish, or even a dog or cat, tortoises can live a long, long, time; unless you’re very young or they’re very old, there’s a decent chance that they’ll outlive you. You should have a plan for this eventuality. After living with your tortoise for a year, talk to friends and family and try to get a feeling for who might be interested in taking over care of your tortoise should something happen to you. Set aside some money to make things easier for whoever agrees to help you and your tortoise out.

8. Is it Worth it?

Tortoises are amazing micro-dinosaurs, beautiful and interesting and tough and easy to care for with the right information. Watching them watching me in my office always feels like taking a fieldtrip millions of years back in time. I’ve loved watching my Redfoot hatchling, Darwin, grow up; also loved, albeit in a different way, helping Chili, the Russian, recover from decades of poor conditions. Once you can manage the basics of care for the species you select, tortoises are among the most unique, fascinating, and longest-lived animals with which you can choose to live.

Jamie Sheffield is a novelist who lives in New Hampshire with six tortoises and a pair of rescue dogs. He can be reached at www.JamieSheffield.com or jsheffield@gmail.com.