International researchers working with scientists at The Technical University of Denmark recently published a paper detailing their discovery of a hum

International researchers working with scientists at The Technical University of Denmark recently published a paper detailing their discovery of a human monoclonal antibody that works against long chain neurotoxins from snake venoms. What is unique about the antibody is the fact that the laboratory trials of the antibody has shown it to be effective against venom from a range of snakes and localities. The prototype treatment has shown to be effective against both African and Asian elapid venomous snakes, including certain cobra, mamba, and krait species.

“We have previously developed antibodies against the venom toxins from single snake species; however, our new results demonstrate that our technology has great potential in neutralizing toxins from multiple species, even from different continents. This broadened cross-neutralization capacity is very promising. It could provide the basis for more effective treatments for snakebite victims in the future,” Andreas Hougaard Laustsen-Kiel, a professor at DTU Bioengineering said in a statement released by the university.

The Egyptian cobra is also known as the snouted cobra. Photo by NickEvansKZN/Shuttertstock

“These are remarkable results,” Hougaard Laustsen-Kiel said. “The antibody we used worked against different neurotoxins derived from different snake species from different parts of the world. These toxins are far from identical but share some crucial similarities in their structure. And apparently, these are just enough for our antibody to display extensive cross-reactivity. We have yet to establish the boundaries of what this antibody can neutralize. Still, we would like to see if it shows the same promise concerning neurotoxins from, for example, the blue krait, the banded krait, and the Egyptian cobra.”

Venomous Snake Bites Every Year

According to the World Health Organization, it is estimated that 5.4 million people are bitten each year by venomous snakes, with about 2.7 million people envenomated by the snakes. The WHO says, of those millions bitten every year, 81,000 to 138,000 people die as result of those snake bites, with agricultural workers and children suffering the most from these bites.

If such an antivenin is approved and released, it could potentially save hundreds of thousands, if not millions of lives. Venomous snake bites, depending on the species, can cause kidney failure, tissue damage and fatal haemorrhage, as well as permanent disability and limb amputation.

Black mambas are one of the fastest snakes in the world. NickEvansKZN/Shutterstock

Most venomous snake bites occur in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Currently, very few countries have the capability and capacity to produce snake venoms to manufacture antivenins, and couple this with the fact that commercial antivenins in one country or locality may not reflect the geographic variation that may occur in venoms of widespread species, the WHO noted.

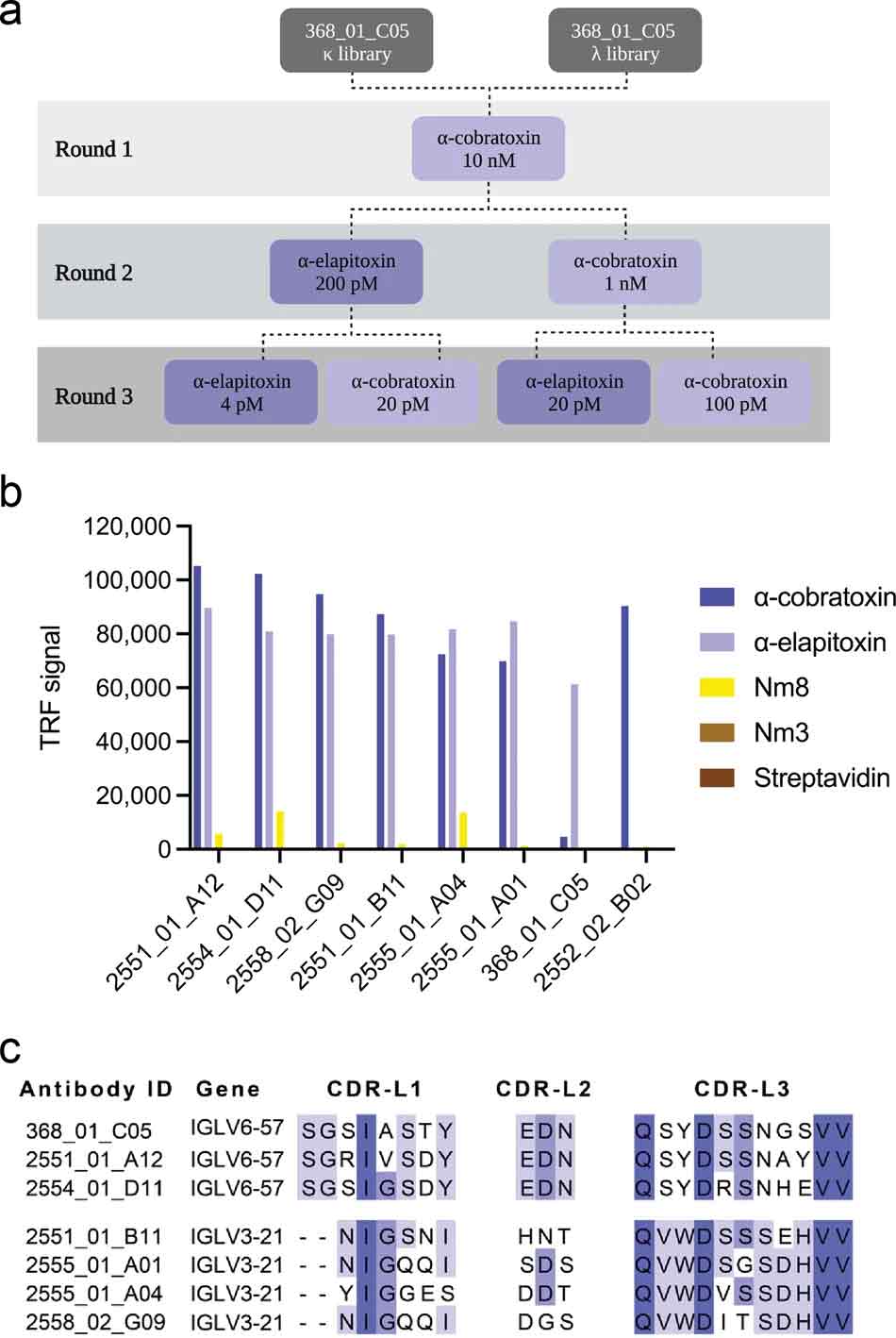

Selection strategy illustrating how cross-panning was performed, including antigen concentrations. b ENC DELFIA showing cross-reactivity of the top six-affinity matured IgGs (2551_01_A12, 2554_01_D11, 2558_02_G09, 2551_01_B11, 2555_01_A04, and 2555_01_A01) in comparison with parental IgG (368_01_C05) and clone 2552_02_B02 from a previously published study15. c Comparison of CDR-L1, CDR-L2, and CDR-L3 sequences for the top six chain-shuffled antibodies and the parental antibody.

In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, according to L’Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), more than 1.5 million people are bit by venomous snakes every year. This results in an estimated 7,000 and 10,000 deaths and 6,000 to 14,000 limb amputations every year. Africa is home to cobras and mambas. Their venoms are neurotoxic in nature and cause respiratory paralysis. Africa is also home to vipers. Viper produce hemorrhagic and necrotic venoms that induces tissue swelling and tissue death in the limbs in which envenomation occurred, and hemorrhaging, which causes death if left untreated.

Universal Snake Bite Antivenin Testing Begins

Top 10 Venomous Snakes Of Australia

The researchers are working on a developing antibodies that are completely of human origin, and this could lead to a more universal antivenin that offers fewer adverse reactions, competitive cost benefits, and when fined tuned, superior efficacy, they noted. The technology that the researchers have employed to create the antibody is called phage display technology, a technique that is described as a popular in vitro methodology within drug discovery. It works by selecting antibodies that bind well to the venom toxins, which then enables broad neutralization of the venoms.

Monocled cobra. Akkharat Jarusilawong/Shutterstock

The researchers worked with hundreds of antibody candidate and have thus far determined that one particular antibody, 2554_01_D11 was very effective in neutralizing the neurotoxins found in venoms of the monocled cobra (Naja kaouthia), forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca) , the spectacled cobra (Naja naja), king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), and the many-banded krait (Bungarus multicinctus). They found that the antibody prevented or delayed death from the venom in all species, and found that with the monocled cobra, the antibody prevented death in envenomed mice.

“In light of the positive results regarding the neutralization of venom from the monocled cobra, we mimicked a true rescue situation, injecting mice with cobra venom and then administering the antibody. And sure enough, we were able to prevent death when the antibody was injected rapidly after envenoming,” José María Gutiérrez, emeritus professor of Instituto Clodomiro Picado, University of Costa Rica said in the statement.

The antibody did not prevent death from the black mamba venom, but rather only prolonged life by several hours. This suggests that the antibody had partial neutralization of the black mamba venom. The black mamba is one of the largest elapid snakes, reaching lengths of about 10 feet. This particular venomous snake is also considered to be one of the most deadly, with a single bite containing enough venom to kill 10 people.

The researchers note that antibodies such as 2554_01_D11 will be helpful in developing future antivenin therapies as well as developing broadly neutralizing antibodies against toxins from other animals, as well as perhaps bacterias, viruses, parasites and possibly used in cancer therapies, the researchers said.

The complete paper, Discovery and optimization of a broadly-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against long-chain α-neurotoxins from snakes,” can be read in the journal Nature.