No matter what brings you into a vet’s office, ask questions, and be comfortable with the choices you make.

As I picked up the leopard tortoise to begin my examination, my client asked, “Gee, Doc, how can you tell what’s going on inside? It’s like a black box.” With the tortoise’s head covered by its front legs and its back legs tucked tightly into its shell, I couldn’t agree more. I was looking at a tan-spotted box, and I had to figure out what was wrong with it. I felt like I was a kid at Christmas trying to figure out what was inside the brightly wrapped package. You can shake, rattle and poke, and still not know if it’s that highly anticipated toy or the new pajamas from grandma.

Photo courtesy Tom Greek

Desert tortoises may be receptive to a vet while other tortoises may hide in their shell.

Chelonians may seem like an impenetrable black box, but veterinarians have some tricks and tools to determine what is going on inside. Some of them you can do. Others should be left to the vet. But both will help you get a thorough examination of your pet and keep it around for years.

Be Observant

The first part of turtle and tortoise health starts at home. No one knows your pet better than you do. You’re the one feeding it, cleaning its cage, and observing and interacting with it on a regular basis.

Therefore you will be the first one to notice something different. It could be something obvious, such as a runny nose or open-mouth breathing, or it could be something more subtle, such as lower activity levels. A professor of mine taught me early on that the key to being a good scientist often lies in the art of observation; the next great discovery may simply be noticing something that someone else missed. At home you will pick up on clues to your pet’s health that your veterinarian would never get to observe.

Playing Sherlock Holmes at home also helps you be a better reptilekeeper. Prevention is such a big part of medicine that keen observations allow you to adjust husbandry to suit individual pets. For example, you may notice that one hatchling is more aggressive at the food bowl than the others. It will probably grow a little quicker, which is not a problem. But there may be one more submissive hatchling that isn’t getting all the food it requires, leading to stress, a decreased immune system and other health problems. Your newfound observation skills allow you to notice this, and then you can remove one or the other from the group, so all hatchlings get what they need.

Physical Exams

In previous articles for REPTILES I’ve stressed the importance of performing physical exams at home, so you can catch problems early, but sometimes you have to bring your pet to the veterinarian. After taking a history (information on husbandry, duration of symptoms, etc.) and observing chelonians in the room, vets perform their physical exams, as well. Starting at the head and working toward the tail, they look for any sign of abnormalities. This includes opening the mouth and palpating into the abdominal cavity.

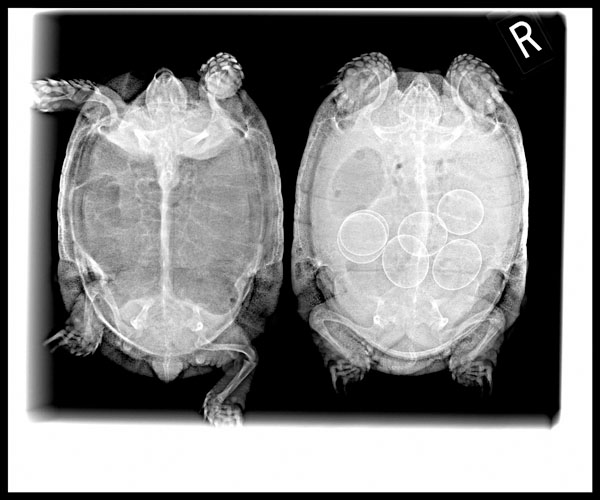

Photo courtesy Tom Greek

X-rays of two female Greek tortoises easily show the eggs inside the tortoise on the bottom.

Some species, such as desert tortoises, are very cooperative. Other species can be less accommodating. Star tortoises notoriously tightly pull in their heads and limbs, making an exam almost impossible. Opening the mouth of a giant alligator snapping turtle can be potentially dangerous, and if a big adult African spurred tortoise doesn’t want you to look in its mouth, it isn’t going to happen. When a pet is less than obliging, sedatives may be needed. There are many that veterinarians use safely on reptiles, and they may make the difference between a thorough examination and a visual assessment. It may mean keeping your pet at the hospital until it is fully recovered before going home, but the extra time is well worth it to get a complete physical exam.

I like to palpate a chelonian’s abdomen by holding the pet with its head up and placing my middle fingers in the leg holes just in front of its rear legs. I rock the animal gently side to side, and masses bounce against my fingers. I may feel eggs, bladder stones, gastrointestinal impactions or other internal masses. You could do this, too, though you may not know whether what you feel is normal or abnormal. Obviously the size of your hands dictates the size of the turtle or tortoise you can palpate (big hands like mine can’t get into the small leg holes of a hatchling) and how strong you feel that day (no reason to throw your back out on a Galapagos tortoise).

Basic Diagnostic Tools

No matter what size the animal, there is still only so much we can see from the outside or palpate on the inside. That’s where more complicated diagnostic testing comes into play. Veterinarians can run a number of routinely used tests to determine what is going on inside that “black box.”

Photo courtesy Tom Greek

A blood sample can give veterinarians a lot of information on a tortoise’s health.

The most common diagnostic tool vets use is a blood test. They can draw a sample from a number of sites around the body, but it does take a little cooperation from the patient. In some stubborn chelonians, light sedation may be required.

An amazing amount of information can be obtained from a blood sample. First vets look at cellular components in the blood. Red blood cells can provide information about anemia or bone marrow health. Changes in white blood cells may indicate infection, parasite infestation, stress and even some cancers. Noncellular components in the blood help vets assess other body organs. Elevations in liver enzymes may indicate liver disease, changes in kidney parameters could be signs of renal disease, and protein levels in the blood help diagnose hydration status and inflammatory diseases. Some blood-born parasites also can be spotted while examining a blood sample.

Additionally, blood can be used to diagnose specific diseases. Research laboratories have started to develop tests for diseases such as mycoplasma, a bacterial pathogen that causes chronic upper-respiratory-tract disease in native U.S. tortoises, and herpes virus, which has caused severe mortality in some imported exotic tortoises.

Another common diagnostic test performed on chelonians is a fecal exam. Parasites are frequent in our pets. Even captive-born and -raised animals can be hosts to a wide variety of them.

Fresh stool samples, ideally less than 24 hours old, are the best for testing. A tortoise that defecates on the way to the veterinarian may be best, but once again our pets don’t always cooperate. Keep the fecal sample refrigerated in a sealed container if you can’t get to your vet right away.

Most veterinarians can do two tests with a stool sample while you wait. The first is a fecal floatation. Some of the feces is mixed with a concentrated salt solution. Eggs of any internal parasites float to the top, making them easier to find. The second test is a direct fecal examination. A small amount of stool is mixed with a little saline and viewed under a microscope. This is great for finding moving organisms that would be killed by the floatation method, such as protozoa. Once veterinarians determine what types of parasites are present, they can pick the appropriate medication to treat your pet.

Cheloniankeepers who own or have access to a microscope can also do these two fecal tests at home. Roger Klingenberg’s book Understanding Reptile Parasites explains how to perform them in detail.

An electrocardiogram, a commonly used test for heart disease in humans, also can be used in animals, including chelonians. Through electrodes attached to the reptile’s skin, it measures the electric pulses coming from contracting heart muscles. The wave pattern will be altered if there is a problem with the cardiac rhythm or musculature. Used along with an echocardiogram, an ultrasound of the heart, this test may help veterinarians diagnose cardiac diseases before they become fatal.

Imaging Techniques

Veterinarians also use imaging techniques to help determine what is going on inside your pet’s body. One type is X-rays. A surprisingly large number of problems can be diagnosed with them. Broken bones are common, and vets can determine treatment options (splints, pins, wires, etc.) based on what bones were fractured. Bladder stones, retained eggs, foreign body ingestion, fecal impaction and pneumonia can all be diagnosed with the aid of X-rays. By adding a contrast media such as barium, vets can follow material through the gastrointestinal system, and look for blockages or motility abnormalities.

Photo courtesy Tom Greek

There is still much to learn about medicine in reptiles and amphibians.

Along with X-rays, other imaging techniques have been used on chelonians. Ultrasound is much better for looking at soft tissue, such as internal organs, but it can’t penetrate though bone. Vets are limited to putting the ultrasonic probe through a tortoise’s leg holes to examine the internal organs, but even with this limitation it can be a useful tool in the diagnostic arsenal.

Endoscopy is promising to be an important tool, as well. Technology is allowing veterinarians to look into a chelonian’s abdominal cavity and lungs, take biopsies of organs, and even determine hatchlings’ sex. Endoscopes of this quality aren’t cheap, so they aren’t something every vet will own. You may need to make a few phone calls before you find someone that can do this.

Photo courtesy Tom Greek

A veterinary technician takes an X-ray of a Galapagos tortoise that wasn’t eating.

Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be available for turtles and tortoises. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional image of the chelonian’s insides, and a vet might use it to examine complex fractures, or osteomyelitis (a bone infection) and neoplasia (tumor) of the skull. CT scans also are very good for evaluation of pulmonary disease. An MRI creates better images of organs and soft tissues than other scanning technologies, and it’s ideal for lesions in the brain and internal organs such as the liver, kidneys and reproductive organs. However, the expense of CT scan and MRI machines and the costs of tests have limited their use for most veterinary patients. More specialty practices are making these technologies available, so they may become commonplace diagnostic options in the future.

Advance Herp Medicine

There is still much to learn about medicine in reptiles and amphibians. One reason is the lack of funding for research in herpetological diseases. You can help to change this. The Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians offers a grant for research and conservation projects to help advance herpetological medicine. Every dollar donated to the ARAV grant program can make a difference. If everyone breeding reptiles donated the value of just a single baby they produced, we could make tremendous strides in identifying and treating diseases in our pets. Donations are tax deductible. Visit arav.org for more information.

Exploratory Surgery

Sometimes diagnostic tests aren’t enough, and vets may have to open that “black box” to see what’s inside.

Exploratory surgery is usually the last resort, and the decision isn’t taken lightly. Surgery in chelonians usually requires cutting through the plastron, and any anesthetic procedure or surgery carries risk of complications, such as death, bleeding and improper healing. Despite the risks, exploratory surgery may help vets determine the cause of the problem, and allow them to perform the procedure to diagnose or even correct it.

It’s Your Decision

With all these options available, people may wonder how they’re supposed to know which one to use and when. Only a discussion between you and your vet can answer that. I have clients that visit every year for a physical, routine blood panel and fecal examinations for their pets. The data we collect help us keep those animals as healthy as possible. Other clients only come in when their pets have a problem, and we discuss the options available to determine the cause and treatment possibilities. No matter what brings you into a vet’s office, ask questions, and be comfortable with the choices you make.

Our turtles and tortoises may seem like an impenetrable black box, but vets do have some tricks and tools to determine what is going on inside. It may not be as fun as determining the best present to open first on Christmas morning, but it will help us keep our chelonian pets healthy for a long time to come.

Tom Greek, M.S., DVM, is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and a Southern California native. His interest in reptiles began at the early age of 5 when he received his first pet snake. He currently practices small- and exotic-animal medicine at Greek & Associates Veterinary Hospital in Yorba Linda, Calif.