Almost everyone who sees them agrees that newts are, in general, endearing little creatures. However, the fact that most are seen in tropical-fish sto

Almost everyone who sees them agrees that newts are, in general, endearing little creatures. However, the fact that most are seen in tropical-fish stores has given many people misconceptions about the care they require. Unlike the tropical fish with which they are often housed, newts are not warm-water creatures. Actually, with few exceptions, the black-spotted newt and the peninsula newt of the United States being just two, newts inhabit cool to cold regions, and they need cool water.

Read More

Eastern Newt Information and Care

Newts occur in North American, European and Asian regions as well as in a few areas in the Middle East. Those that do occur in southerly areas are almost always restricted to cool, montane waters and equally cool, moist woodlands surrounding such habitats.

A few do diverge from this lifestyle. The terrestrial habitats surrounding the home streams of Kaiser’s spotted newt (Neurergus kaiseri) in Iran, for example, are semiarid scrublands, and they seem relatively inhospitable. Because of habitat decline and overcollection, this newt is listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered. Unavailable in pet stores, Kaiser’s newt is really only seen in zoo captive-breeding programs and among a few private hobbyists.

Newts (along with fire salamanders, spectacled salamanders and gold-striped salamanders) are members of the family Salamandridae, which contains about 20 genera and 74 species. It is important to note that all newts are salamanders, but not all salamanders are newts. It is like all robins are birds, but not all birds are robins. Many of these salamanders, being terrestrial at times and aquatic at other times, have complex life histories. Although a few high-altitude populations of the salamander types birth live young, all newts are oviparous. Females usually attach eggs to submerged plants, rocks or sticks.

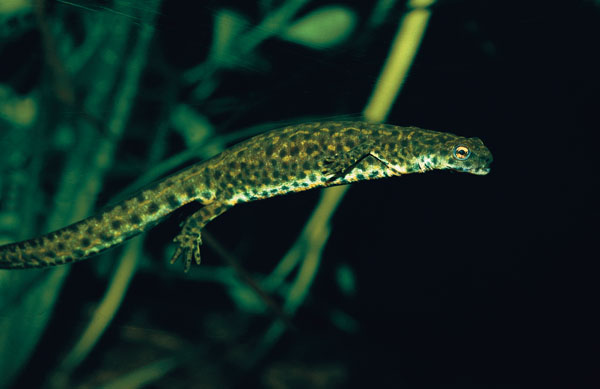

Dick Bartlett

The black-spotted newt (Notophthalmus meridionalis) can be found in Texas and northeastern Mexico.

Newts are usually relatively dark (brown, olive, tan or green) dorsally, but they may have brilliant reds, oranges or yellows ventrally. However, this isn’t always the case. When terrestrial conditions allow, such as during the intermediate land stage called the eft stage, the red-spotted newt may assume roughened skin that is a brilliant red overall. The red coloration is an aposematic adaptation that advertises the toxic glandular secretions produced by this tiny woodland wanderer. So poisonous are its secretions that there are records of fatalities to predators that have eaten the eft.

Only a handful of the species in the Salamandridae family are commonly seen as captives. Many species are now protected at the state or country level. Many European and Asian species are so rarely seen that there still is little known about their life histories.

There are six species of newts in the United States. Three are in the eastern and central states, and three are in the Pacific states. These are contained in two genera. The eastern and central newts are in the genus Notophthalmus, and those in the West are in the genus Taricha.

Newts of the Eastern U.S.

Of the eastern newts, N. viridescens is the most well known to hobbyists. This species has long been accepted as having four subspecies. The red-spotted newt (N. v. viridescens) has black-edged, red dorsolateral spots. The broken-striped newt (N. v. dorsalis) has interrupted black-edged, red dorsolateral stripes. The central newt (N. v. louisianensis) has red dorsolateral spots lacking black rims, and the peninsula newt (N. v. piaropicola) lacks red dorsolateral spots entirely. However, it has recently been suggested that the defining morphological characteristics of these forms overlap so widely that all subspecies are invalid.

DICK BARTLETT

The terrestrial eft stage of the red-spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens) may be found in cool, moist woodlands.

The red-spotted newt ranges from Canada’s Maritime Provinces and south-central Ontario to the montane areas of Alabama and Georgia in the U.S. The broken-striped newt is restricted to the coastal plain and piedmont areas of the Carolinas. The central newt occurs from southwestern Ontario to eastern Texas, northern Florida and southeastern South Carolina. The peninsula newt is found only on the Florida Peninsula.

The remaining two species of eastern newts are the striped newt (N. perstriatus) of Florida and Georgia, and the black-spotted newt (N. meridionalis) of Texas and northeastern Mexico. Neither is present in the pet trade. The striped newt is uncommon, and the black-spotted newt is rare and protected in the wild.

DICK BARTLETT

This adult striped newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus) is from north-central Florida.

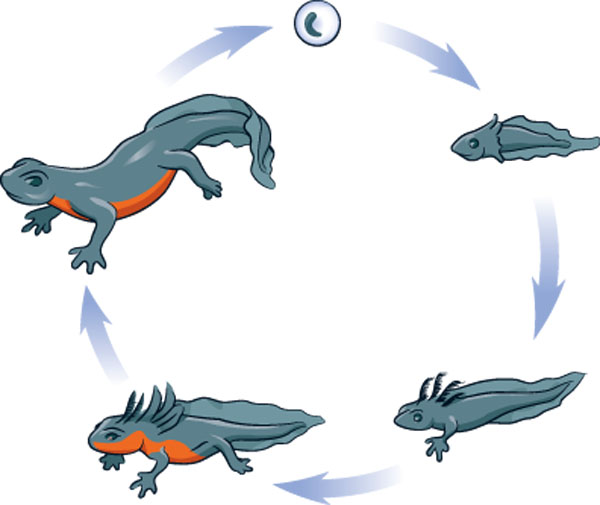

Although most newts have a complex life history, the histories of the red-spotted and striped newts are especially so. The life history of the related black-spotted newts is, seemingly, a bit less complex than that of congeners.

Adults from the Notophthalmus genus are usually aquatic, but they may assume a terrestrial mode if their home pond dries. In the spring, during the year that breeding by the aquatic adults occurs, the single eggs are attached to submerged plant stems or pond debris. After hatching, the gilled larvae remain aquatic for a period of two to more than five months. They rarely overwinter. Then they either metamorphose into gilled (neotenic) adults or, in many populations, into the terrestrial red eft. Larval size may vary from about 21⁄2 to 3 inches before metamorphosis into gilled adults. Larvae of populations that metamorphose into efts are a bit less than 2 inches in total length at metamorphosis. Gilled adults may metamorphose fully and become terrestrial if their ponds dry.

Although the newts of other genera may lack a well-defined eft stage following their metamorphosis from the aquatic larval stage, the juveniles of many species live a terrestrial existence for a year or more. The adults of almost all species undergo well-developed, annual terrestrial and aquatic cycles.

It is during the aquatic cycle that all breed. During the breeding season the males develop broad caudal fins; enlarged hind limbs with black, horny outgrowths on the inner surfaces; and a swollen vent. Males, apparently drawn by female pheromones, often come to shallow areas of quiet water where reproductively active females have congregated. During courtship a male may grasp (amplex) a female around her shoulders with his hind legs, or he may make undulatory movements of his body and tail while stationed in front of her. The undulations create a weak water current that disperses stimulatory pheromones. The female induces the male to deposit a spermatophore by nudging his tail with her snout. Females may lay more than 350 eggs. A few are laid each day until the complement has been expended.

Of the eastern newts, the red-spotted newt and the central newt can be found in the hobby via pet stores, the Internet or a local hobbyist.

Newts of the Western U.S.

The western newts are also called the Pacific newts. The coastal-range newt (Taricha t. torosa), also called the California newt, ranges northward from San Diego County, Calif., to northwestern California. A second subspecies, the Sierra newt (T. torosa sierrae), also often called the California newt just like T. t. torosa, occurs in California’s Sierra Nevada range.

DICK BARTLETT

The California red-bellied newt (Taricha rivularis) is found in damp, redwood-shaded woodlands in northwestern California.

The rough-skinned newt (T. g. granulosa), which actually has smooth skin when it is in breeding condition, may be found in coastal habitats from around San Francisco Bay to southeastern Alaska. A questionably valid subspecies, the Crater Lake rough-skinned newt (T. g. mazamae), is found only in Crater Lake, Ore.

The third species, the California red-bellied newt (T. rivularis), is restricted in distribution to damp redwood-shaded woodlands in a small area of northwestern California.

The three Pacific newts are quite similar, and all are capable of hybridizing. The brown eyes, salmon-colored belly and broad, dark bar crossing the vent makes the red-bellied newt the most distinctive of the three. When viewed from above, the eye outline of the two T. granulosa subspecies does not extend to the outline of the jaw. The California red-bellied newt and the Sierra newt, however, when viewed in the same way, have the eye outline protruding a bit beyond the jaw line. Although variable, the back and sides are often a dark brown, and the yellow to orange of the belly is sharply delineated. The dark-brown sides of the Crater Lake newt wrap well around the trunk onto the belly. The coastal newt tends to be light-brown with a yellow-orange belly. The montane Sierra subspecies is much more intensely colored than its coastal cousin. The bright reddish-orange of the belly contrasts vividly with the deep brown of the back. It is nearly as beautifully colored as the California red-bellied newt.

The rough-skinned newt (T. g. granulosa) is the most commonly available of the Pacific species, but it is often sold in error as the California newt (T. t. torosa). The California red-bellied newt (T. rivularis) is almost never available.

A Few Old World Newts

The males of many species of Old World newts display spectacular vertebral fins during the breeding season, and hobbyists covet them because of this. Among these are the two species of the Near Eastern banded newts (Ommatotriton spp.). Males of these also develop fins on the toes of their hind feet.

Adults of the Old World newts vary in length. The smooth newt and its relatives (Lissotriton spp.) measure about 31⁄2 inches in overall length, but the crested newts of the Triturus cristatus complex measure 7 inches in total length.

A favorite of many collectors has been the colorful marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus) of France, Spain and Portugal. It was traditionally divided into two subspecies: the marbled newt (T. m. marmoratus) and the pygmy marbled newt (T. m. pygmaeus). However, most taxonomists now consider these two full species. The familiar common names remain unchanged.

DICK BARTLETT

The broken-striped newt (Notophthalmus viridescens dorsalis) inhabits the sandhill areas of the Carolinas.

Although the predominating color of the marbled newts is variable, most are a pretty moss-green. Triturus m. marmoratus, which reaches a length up to 6 inches, tends to be more heavily marbled with black. Most have bold, black lateral vermiculations; black dorsal spots; an orange vertebral line; and a dusk-colored belly. However, black may be the predominate color on some. Triturus m. pygmaeus, which reaches lengths up to 41⁄2 inches, tends to bear much less black on the sides, and it has a lighter belly. Rarely do the black markings on this subspecies have a bronzy overwash.

Marbled newts differ in appearance from crested newts, which are dark brown dorsally and brilliant orange with dark spots ventrally, but both newts are rather closely related. Marbled newts not only interbreed readily with each other but also with the crested newts where ranges overlap.

Newt life cycle.

A strange and distressing naturally occurring malady plagues both crested and marbled newts. About 50 percent of the developing larvae perish in the egg at the tail-bud-formation stage. This is termed the “50-percent abortion genetic effect.”

As mentioned earlier, juveniles of many Old World newts are persistently terrestrial (larvae are aquatic), but they become at least seasonally aquatic with age. The skin of caudatans in their terrestrial stage tends to be warty or granulate. When newts are aquatic, they become smoother skinned.

Availability of European and Asiatic newts in the general pet trade is sporadic. Currently, Triturus marmoratus is periodically available in small numbers from two or three dealers. Triturus pygmaeus is unavailable and listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Newt Captive Care

Most newt species will thrive as captives as long as their food, temperature, habitat and water-quality requirements are met.

Newts are carnivorous, feeding upon all manner of tiny invertebrates. Captives eat pinhead crickets, chopped earthworms, black worms, bloodworms and daphnia.

DICK BARTLETT

The rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) is one of three species found in Pacific Coast states.

Enclosure size depends upon how many newts are kept. A 5-gallon tank is sufficient for one or two of the small species. If you have a dozen or more, you may want a 20- to 75-gallon tank.

How much of the terrarium needs to be devoted to water depends upon the species you keep and whether they are in a terrestrial or aquatic stage. Some species can survive for decades in a cool, all-water aquarium. All of the Pacific newts are primarily terrestrial, but they can and do enter water periodically, especially during drought and always for breeding. Always research the specific newt you wish to keep before purchasing one and setting up an aquarium or terrarium.

For most newts, summer terrarium temperatures of 65 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit are ideal. Short periods of somewhat higher temperatures, around 75 degrees, is tolerated. The peninsula newt and black-spotted newt are able to tolerate temperatures a bit higher. For these species, a low of 70 degrees and a high of 80 degrees are fine. Winter temperatures 5 to 10 degrees lower than those provided in summer may help cycle captive newts for breeding. They remain active at these temperatures. However, if you drop them into near-freezing water, they will hibernate.

There are indications that extended periods of extreme temperatures for newts (the 40s or 50s, or the mid-70s or higher) may cause skeletal deformities or weakness, and it even may alter sex ratios in the developing newt larvae of some species. It is best to provide moderate temperatures and to avoid the extremes.

DICK BARTLETT

The striped newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus) is found in Florida and Georgia.

Cages, whether terraria or aquaria, must be maintained scrupulously clean. Water pH, however, is not a great concern. Chlorines and chloramines can be tolerated, but it is better to remove them.

Although some newt species are readily available to hobbyists, most species are not able to survive long periods in warm water (tropical) aquaria. Unless you are able to provide a cooled terrarium or a cool-water aquarium, many newt species — especially European, Asian and our Pacific Coast species — will struggle to survive in captivity.

On the other hand, when their biological needs are adequately met, captives may survive for several decades, and they can be beautiful, rewarding terrarium pets. Research the natural history of any newt species you hope to maintain, and be certain that you are able to provide at least its minimum care requirements — including (but certainly not limited to) habitat, temperature and food preferences.

Dick Bartlett is a herpetologist-herpetoculturist who has written hundreds of articles and many books, some with his wife Patti. He has bred 175 captive herp species.