I get a zillion e-mails and calls asking advice about herp cases. This morning, I got a frantic call from a veterinarian about a large python that was

I get a zillion e-mails and calls asking advice about herp cases. This morning, I got a frantic call from a veterinarian about a large python that was showing signs of inclusion body disease. He wanted to know if there were any new, life-saving treatments that he could try. I reviewed the disease, talked about possible medications he could use and told him that there was nothing new. The prognosis was generally considered grave, meaning that it will die. My final words were, “Provide supportive care and hope for a miracle.”

Read More

IBD Blood Test Developed for Pythons and Boas

Symptoms For Inclusion Body Disease In Snakes

Douglas Mader

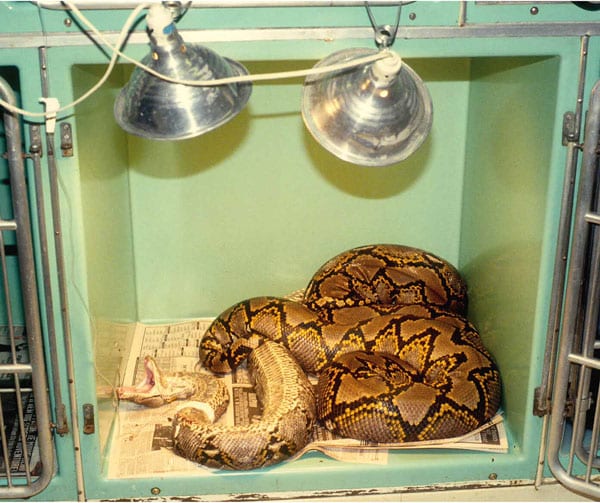

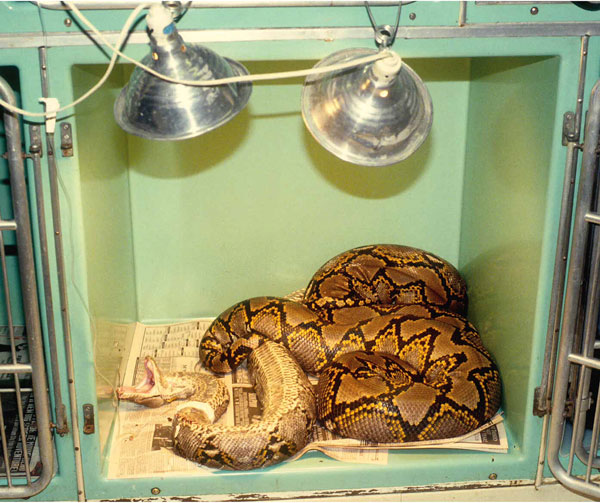

This reticulated python had viral encephalitis and survived after 63 days of treatment.

After I hung up, I remembered an unusual case that I had many years ago.

It began with a phone call the day before Christmas. Because of the nature of my veterinary practice, a call from a frantic snake owner was not uncommon. You see, my hospital in Southern California specialized in non-traditional pets, the kind that slither, creep, fly, scratch, hoot, burrow and any combination thereof. So when the caller claimed that her pet snake could not crawl normally, it did not strike me at all as weird. The fact that she was calling on the morning before Christmas was not odd—pets never schedule a convenient time to get sick. But what was a bit unusual, was that she was calling from Texas.

It wasn’t busy, so I took the call. Obviously, there was not a lot I could do for her over the phone, but I could at least talk to her and perhaps give her some advice that might help. Sometimes, just letting a person talk makes all the difference in the world.

It turned out that her snake had been sick for several weeks. It had been to two veterinarians that had tried treating it with various antibiotics, to no avail. She was afraid that it was going to die. She did not have any other pets, and her 7 year-old daughter only wanted one thing for Christmas—for Santa to make her snake better.

The woman described the snake’s symptoms—unable to crawl, rolling over on its back, lolling of its head from side to side and, to top it off, it had not eaten in three months! The lack of appetite did not bother me. Large snakes can go as long as a year between meals in some situations.

However, the other symptoms were extremely serious. I explained this to the owner, and apologized that there really wasn’t anything that I could do for her or her snake over the phone.

“What if she could get the snake to me?” she asked.

Of course, I could take a look, but even if I did see the snake, judging by the symptoms that she described, the prognosis sounded grave. I told her that I was very sorry, and I wished her the best.

The snake had belonged to her husband. He was a cross-country trucker and would keep the snake in his cab, much the same way most truckers kept dogs in their trucks for company during the long hauls. Apparently, the husband had fallen asleep at the wheel on his way home on Christmas Eve the year before. The truck went off the road, crashing and killing him instantly. The highway patrol officers found the snake alive in the cab.

The snake was the link to their loved one—the husband and father. I felt badly for them.

On Christmas morning, while the hospital was closed, the day nurse was alone in the hospital performing treatments. An incessant pounding at the door interrupted the Christmas carols playing on the radio in the ward. After he let the person in, he called me at home.

“Dr. Mader, you need to come to the hospital right away.”

My wife, an ICU nurse at the local human hospital, was working the holiday shift. I was home alone with my dog, Wok, drinking hot cider and reading from a stack of journals piled high on my desk.

Christmas morning. What difference did it make? “Sure, I’ll come in,” I told the technician.

“We drove all night.” The woman’s skin was pale, dark circles under her eyes. She looked exhausted. Her daughter, red pig-tails and dressed in a puffy lime-green down jacket, was asleep on the couch in the reception area when I arrived. “We only stopped for gas and something to eat.”

The little girl’s head was resting on the edge of a large burlap sack. To my surprise, coiled up inside, was a cold, lifeless very thin reticulated python—nearly 18 feet long!

I examined the snake from the flicking tongue to tip of the tail—all 6 yards of it. After I was finished, I took a blood sample and some x-rays. Reviewing all the information with the owner, I gave her the bad news.

“It looks like your pet has viral encephalitis—an infection in the brain.” This is a very serious condition, one that usually ends up with the pet being humanely euthanized.

“You have to do something, doctor. I drove out all the way from Texas. It was my Christmas present for my daughter.” Tears moistened her eyes. “It is her only memory of her father.”

I took the snake to the treatment area. With the help of my nurse, we placed an intravenous catheter in the snake’s jugular, started it on warm IV fluids, gave it food and vitamins through the veins, initiated antibiotics and antiviral drugs, and placed it in a large incubator in order to warm its lifeless body.

A couple of hours later I went back to the reception area to find both mom and daughter sound asleep on the couch. I woke them to give them an update, and then offered to take them to dinner. Being Christmas, there wasn’t much to choose from, so we celebrated the holiday at a Jack in the Box.

Sixty-three days later, mom and daughter made the return trip back from Texas to Southern California to pick up their pet snake. It had been off all medications for two weeks, and in the meantime, had eaten two large meals. I felt confident that it was going to be okay. Given that snakes can live for 25 to 30 years, the little girl would have memories of her father for years to come.

I guess miracles can happen.

Douglas R. MADER, MS, DVM, DABVP (REPTILE/AMPHIBIAN), is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He owns the Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Conch Republic, and is a world-renowned lecturer, author and editor. He sits on the review boards of several scientific and veterinary journals.