Find out what ails your tortoise and potential remedies.

I have been keeping tortoises as pets for almost 40 years, and my boyhood fascination with these unique reptiles grew into a veterinary career that has allowed me to provide medical and surgical care for pets, as well as research benefiting tortoises, field work and other efforts that promote conservation.

This article provides a brief overview of the more common health problems I see in tortoises. It is based on research by others, myself, and personal experiences treating a lot of tortoises over the past 25 years.

reptiles4all/shutterstock

When choosing a pet tortoise, hobbyists must remember that they are making what could become a lifetime commitment. This sulcata, for instance, could live for longer than 70 years.

When Acquiring A Tortoise, Always Plan Ahead

When selecting a pet tortoise, hobbyists should consider the care that they will be able to provide over the tortoise’s lifetime. Many tortoises live 50 to 100 years, and sometimes longer if properly cared for. Owning a tortoise, therefore, is a long-term commitment and should not be made as an impulse decision.

Consider what sort of space you will be able to provide. While an aquarium may be sufficient for a new hatchling tortoise, as it grows more space will be needed. Most tortoises in the wild inhabit large areas of land with multiple burrows or shelters they travel between. With the exception of a few smaller species, such as the Russian tortoise, outdoor enclosures or custom indoor enclosures larger than standard aquariums are going to be needed to provide proper space for a tortoise as it grows.

Improper care is the most common underlying problem behind most tortoises’ health issues. The best way to keep a tortoise healthy is to research where the tortoise is from — what environment it lives in, and what it eats — and then try to mimic that in the diet and husbandry you provide. Tortoises have remained relatively unchanged for a few million years, adapting to have long life spans in the environments they inhabit. Trying to make them live in ways and eat things they did not evolve to increases the risk of all of the following conditions to occur.

Shell Pyramiding In Tortoises

Shell pyramiding is a condition in which the scutes of a tortoise’s carapace are raised up in the center relative to their margins. Two published research studies have been performed which link the condition to low environmental humidity in sulcatas and being provided supplemental nighttime heat in sulcatas and leopard tortoises. The condition has little to do with diet other than the faster the tortoise grows, the more apparent the pyramiding becomes when environmental problems are present.

Many desert tortoise species spend a lot of time in burrows where humidity is much higher than above ground. Aquariums and enclosures often have very low humidity due to the dry air in our homes and the use of supplemental heat lamps.

Jay johnson

This desert tortoise is exhibiting both shell pyramiding and a depressed carapace resulting from weak, unhealthy carapace bones during development.

It is best to provide a humid burrow-like hiding area for tortoises kept indoors. This can be accomplished using a commercially available domed wooden log soaked one or two times a week in water, or by placing moistened (slightly damp, not wet) substrate in or under hiding areas. It is also important to let nighttime temperatures drop into the upper 60s to mid 70s Fahrenheit for most species. In most cases, no supplemental night heat beyond the temperature at which we keep our homes is required.

Bone Diseases In Tortoises

Numerous conditions can cause bone disorders in tortoises. Many of these are referred to collectively as metabolic bone diseases by reptile owners. An entire article could be written on bone diseases of reptiles and is beyond the scope of this article, but common causes of bone disease include insufficient calcium in the diet, insufficient exposure to UVB light, vitamin and nutrient deficiencies, and other illnesses.

jay johnson

This desert tortoise has exposed carapace bone along the marginals after having been chewed on by a dog.

Explained simply, calcium is needed for bone growth, and calcium and vitamin D both need to be ingested by the tortoise. Vitamin D is absorbed and converted by the tortoise’s body to vitamin D3 when the tortoise is exposed to UVB light. Vitamin D3 is important for absorption of calcium from the gut and getting it to the bones. Protein, other vitamins and other minerals are also important for proper bone development and maintenance.

Lack of needed calcium, vitamins, minerals and protein in a tortoise’s diet can lead to soft or weak bones. This often manifests as a soft shell, weak legs, and other developmental deformities. If corrected early enough, most tortoises will survive but can be left with lifelong deformities.

Too much vitamin D3 can cause health problems also, so supplementation should be limited. It is best to make sure a tortoise’s diet includes items rich in vitamin D and that the animals have routine exposure to natural sunlight or UVB lighting for reptiles.

In general, for juveniles and other tortoises housed indoors, I recommend calcium be dusted on their food twice a week and a reptile multivitamin once weekly.

Respiratory Infections In Tortoises

Respiratory infections are very common in tortoises. Upper respiratory infections are the most common, but lower respiratory infections (pneumonia) also occur.

One of the most common causes of upper respiratory infections are Mycoplasma bacteria, though other bacteria and viruses may also be causes. Signs include a runny nose, bubbles from the nose, erosion of the nares, swelling around the eyes, and conjunctivitis (reddened, inflamed eyes). Flushing mucus and exudate out of the tortoise’s sinus cavity along with proper antibiotic therapy is often needed to resolve illness. Tortoises with Mycoplasma are often infected for life, and flare-ups during times of stress or immunocompromise are common.

jay johnson

A desert tortoise presenting nasal discharge associated with an upper respiratory infection.

Lower respiratory Infections are more significant and require more aggressive treatment. Symptoms include labored breathing (indicated by a tortoise extending its neck and moving its front legs in and out in order to breathe), weakness, lethargy, sunken eyes, and other signs. Radiographs (X-rays) are usually needed to diagnose lower respiratory infections, and a lung wash to collect samples for cytology and culture should be performed when possible to provide the best treatment.

Trauma In Tortoises

Trauma can occur from numerous causes, including vehicles, lawnmowers, birds, ants, and other animals. By far, the most common source of trauma in tortoises occurs from dogs. In my experience, even the best-trained dogs will unexpectedly decide to chew on a tortoise without warning. Dog bite trauma usually results in punctures to the tortoise’s shell, as well as the chewing off of themarginal scutes, legs, and skin. In many cases, death is the result.

jay johnson

Car tire trauma to a desert tortoise.

If a dog attacks your tortoise, and wounds penetrate the skin or shell, medical care is often needed. If wounds do not penetrate the body cavity, you should flush them with water to remove as much dog saliva, dirt, and debris as possible. Then take your tortoise to a reptile veterinarian as soon as possible to start further wound care, antibiotic therapy, and pain management.

Most wounds should be managed open with ongoing bandage changes and wound care. Fiberglass and epoxy patches were common shell repair methods in the past; today, these should only be used to close openings into the body cavity or large, unstable shell fractures.

Parasites In Tortoises

Parasitic health-related problems are relatively common in tortoises, and parasites can infect the intestinal tract, tissues of the body, or feed on the shell and skin. Not all parasites cause harm to tortoises; some may even be beneficial to certain tortoises.

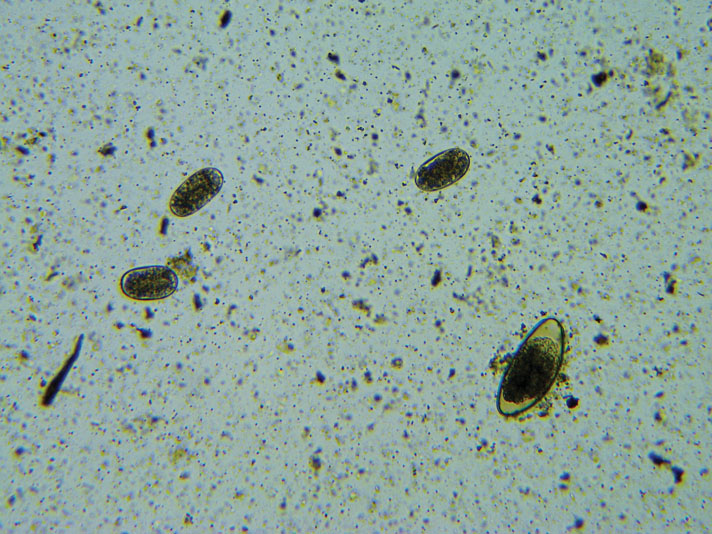

jay johnson

A pinworm egg is pictured in the lower right corner, and three hookworm eggs are above and to the left of it.

Diagnosing parasites in tortoises can require tests different from those performed frequently on mammals. With regard to intestinal parasites, I highly recommend testing at least one fecal sample, and a second sample one month later, for parasites after acquiring a new tortoise, and especially before placing it in an enclosure with other existing tortoises. The fecal sample being tested should be recently passed, kept moist by wrapping it in a wet paper towel placed in a plastic bag and not allowed to get too hot or cold. Time outside of the body, drying, heat, and cold can decrease our ability to detect certain types of intestinal parasites. Make sure your veterinarian performs a “direct” fecal test looking for protozoans in addition to the standard floatation test.

Different types of parasites require different types of treatments, so it is important to identify and treat parasites of concern properly. Routine deworming is becoming less popular due to increasing parasite resistance to medications, the understanding being that not all parasites are problematic and administration of anti-parasitic medications can potentially cause illness if a tortoise is not dosed properly or if the animal has a reaction to them.

Certain types or low numbers of intestinal protozoans are often normal, do not cause problems, and do not require treatment. Pinworms are present in most tortoises and rarely need treatment. These should be differentiated from other nematode parasites in which treatment is often recommended, however. Also, numbers of “normal” parasites may increase to levels that cause illness when tortoises are not provided proper diets and husbandry. Many tortoises, for instance, are fed too much produce and need more grass or high-fiber plant leaves and stems in their diet.

Feeding, drinking, and defecating in the same small area day after day can lead to a parasite load that’s higher than normal. Tortoises often like to sit in their water bowls, and defecate and drink at the same time.

It’s important that you work with a knowledgeable reptile veterinarian, and it is also important that routine cage cleaning and sanitation occurs. Water bowls can be a source of increased intestinal parasite problems, and they do not need to be provided more weekly for most tortoises. Water bowls and cages should be cleaned with dilute household bleach (9 parts water mixed with 1 part bleach), rinsed well, and allowed to air dry prior to reuse.

Dystocia (Egg Binding) In Tortoises

Egg binding can occur due to insufficient calcium in a female tortoise’s diet, as calcium is needed for muscle contractions that move the eggs through the reproductive tract, as well as bladder stones preventing eggs from passing, infections, lack of a proper place to lay eggs, and reproductive tract diseases.

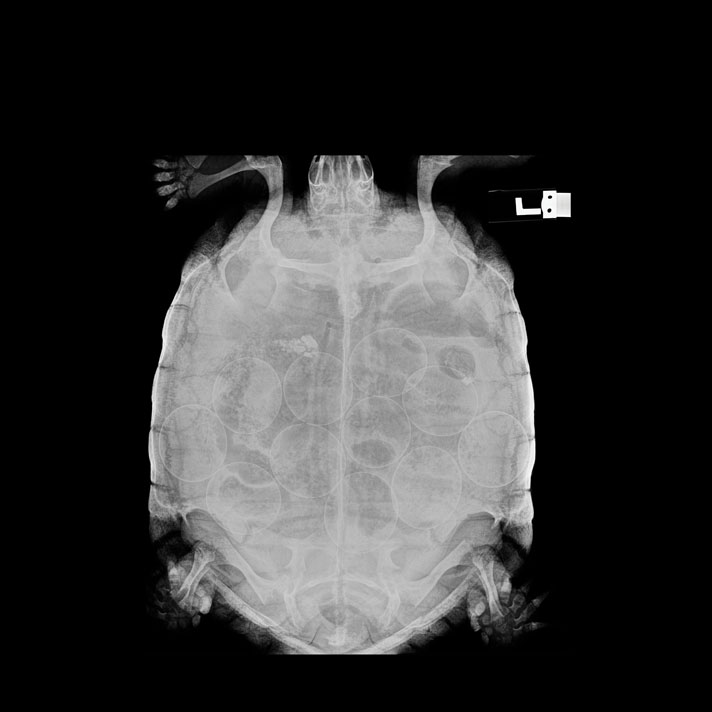

Symptoms of dystocia can include nest-digging behavior without eggs being laid, straining, weakness/lethargy, and decreased appetite. Radiographs are often needed to diagnose this problem, though finding eggs on an X-ray does not always mean that is the primary problem. Depending on the cause of the dystocia, medical or surgical treatments are often needed. Medical treatment may also be initiated to induce egg laying and if surgery is unsuccessful.

Jayjohnson

This is a radiograph of a desert tortoise with dystocia, taken six months after the normal oviposition time; note the retained eggs.

Routine sterilization of tortoises is becoming more common with the recent development of procedures by myself and others that allow the removal of the ovaries, plus or minus other parts of the reproductive tract, without cutting the tortoise’s shell. Incisions are made in front of the back legs, and reproductive organs are removed. Proactive sterilization prevents egg-laying-related health problems and egg laying from females where it is not desired.

Bladder Stones In Tortoises

Most tortoises have a large bladder in which they store urine. The urine serves as a source of water to prevent dehydration during times of drought. It is also used to regulate potassium and get rid of urea and uric acid (the waste products of protein metabolism). Potassium and uric acid are bound together and excreted as potassium urates. This is the white, tan or gray chalky substance often found in tortoise urine.

Most tortoises will accumulate urates in the bladder over time, and in the wild, when water is available to drink, they will purge their bladders, getting rid of the urine and urates. They are then refilled with fresh, new urine.

jay johnson

This radiograph shows a bladder stone inside a desert tortoise.

In some tortoises, the urates start binding together, forming a “stone.” Tortoises often pass small stones through their large urethras, but if a stone grows too large, it can no longer be passed. Most stones continue to grow over time, and these can eventually cause health problems.

Clinical signs associated with bladder stones are straining, abnormal walking due to pain or pressure on the pelvis, and signs of general illness. Veterinarians skilled at examining tortoises can usually palpate or feel a stone (or stones) inside the tortoise when performing an exam. A radiograph, however, is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Tortoise bladder stones cannot be dissolved with special diets, they have to be removed. The “classic” method, which is sometimes still needed for very large stones, involves cutting a hole through the plastron and removing the stone. Myself and Dr. Berney Mangone, however, developed a technique to remove bladder stones surgically through the space in front of the hind leg while attending veterinary school. This technique was further improved upon by Dr. Nadine Lamberski from the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, and now most stones can be surgically removed without cutting the tortoise’s shell.

The cause of bladder stones is unknown. They occur much more frequently in captive than wild tortoises. In some cases, it is clear that an egg passed up the urethra into the bladder, forming a nidus that the stone formed around. Since stones are made up of potassium and uric acid, excessive amounts or an imbalance of potassium and protein in the diet are likely contributors. Hydration may have an effect; however, dehydration occurs more frequently in wild tortoises that have a lower incidence of stones.

I also believe that tortoises that do not develop a routine of purging their bladder to get rid of urine and urates are more at risk. When tortoises have water available at all times, they may drink smaller, more frequent amounts and urinate smaller, more frequent amounts, which does not result in urates being purged. I recommend limiting high potassium food items and only providing water at a maximum of weekly for most healthy tortoises.

Viral Diseases In Tortoises

A large number of viruses have been reported in many different tortoise species. Some have viruses that are “normal” for them, and these viruses do not cause illness unless the tortoise’s immune system is compromised, or they get into a species that is not a normal host.

One good example of this are herpes viruses. Many tortoise species have their own herpes virus that does not cause illness unless their immune system is compromised or other illness is present. The herpes viruses common in Russian tortoises and other Testudo species can often cause severe and often fatal illness in desert tortoises and other Gopherus species.

jay johnson

Having a good working relationship with a reptile veterinarian is key to long-term health for pet tortoises.

For this reason, it is not a good idea to mix different tortoise species in the same enclosures, and also make sure cages, bowls, etc., are cleaned thoroughly and disinfected between use with different tortoises. It is also a good practice to wash your hands well between handling different groups of tortoises, and don’t walk directly from one pen into another.

As mentioned throughout this article, proper diet and husbandry are very important to maintain good health. It is also a good idea to quarantine new tortoises from others for at least 30 days (or ideally, 90 days). During the quarantine period, weights, feedings and other observations/activities should be recorded. At least one, and ideally two, fecal parasite tests should be performed. Additional tests for infectious diseases may be indicated, depending on species.

Work with a knowledgeable reptile veterinarian to maintain proper health and deal with illness if it arises. The Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians is a good resource to help locate veterinarians with an interest in reptile medicine and surgery; visit their webpage at arav.org.

Jay Johnson, DVM, received a BS in veterinary sciences from the University of Arizona in 1992, a veterinary degree from Colorado State University in 1996, and in 2007 opened the Arizona Exotics Animal Hospital (azeah.com). He has participated in chelonian research and conservation projects with, among other groups, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. He is a past president of the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians, teaches biologists and veterinarians, and volunteers veterinary care for the Arizona Game and Fish Department’s desert tortoise adoption program. And he still finds time to enjoy the 40 tortoises he maintains at home.